S

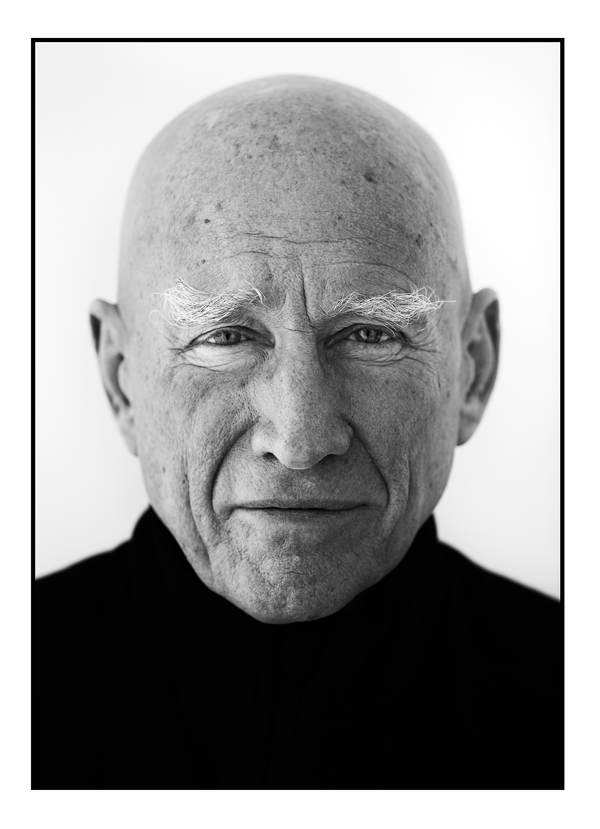

Sebastiao Salgado is a Brazilian-born photographer, who began his career as an economist. Today he is considered a living legend in the sphere of photography. He has committed himself to long-term projects, all of which are substantial in nature. He connects with his subjects on a deeply personal level, and is totally absorbed in black and white photography. His work is held in major museum collections worldwide and he is also credited with numerous photographic books. Recently he finished an impressive project titled

GENESIS, the result of an epic eight- year expedition to rediscover the mountains, deserts, oceans, and the animals and peoples that have so far escaped the imprint of modern culture and technology.

Peter Fetterman is an internationally recognized Fine Art Photography dealer, and is currently exhibiting many of Sebastiao Salgado’s photographs from the project “

GENESIS” at his gallery, which is located at Bergamot Station in Santa Monica. I had an opportunity to interview Peter about his long association and friendship with

Sebastião

Salgado to learn more about this exceptional photographer.

AF: Peter, before we get started, I wanted to personally congratulate you on your quarter of a century success and the dedication you’ve shown with your fine Photography Gallery located here in Los Angeles.

PF: Thank you... 25 incredible years...

AF: By bringing significant photography, both vintage and contemporary to the Los Angeles community and also by educating and supporting not only the collectors and engaging with them, but what you’ve done for the photographers you’ve exhibited through the years, the sales you’ve made on their behalf and by promoting the art of photography in general with such passion.

PF: It’s kind of you to say that.

AF:

AF: Well, it’s true. It’s all true. I have a few questions about the current exhibition you’re hosting by photographer

Sebastiao

Salgado. So we might was well just jump right into it..... When did you first become aware of

Sebastiao

Salgado’s work?

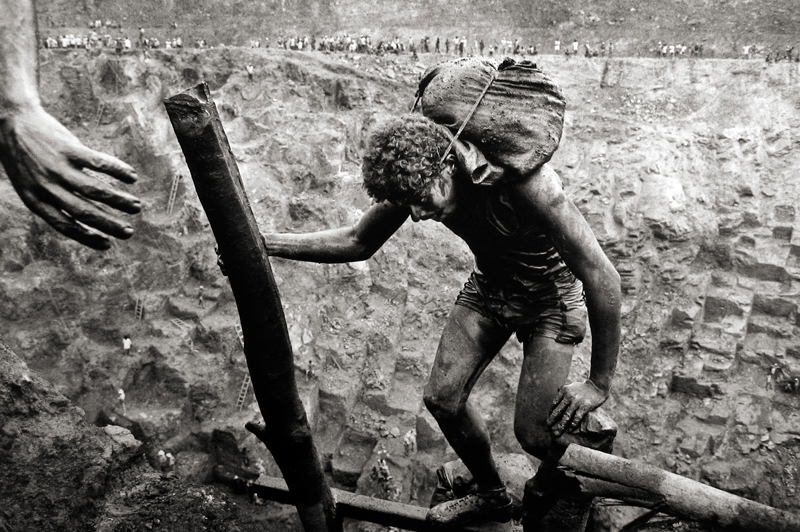

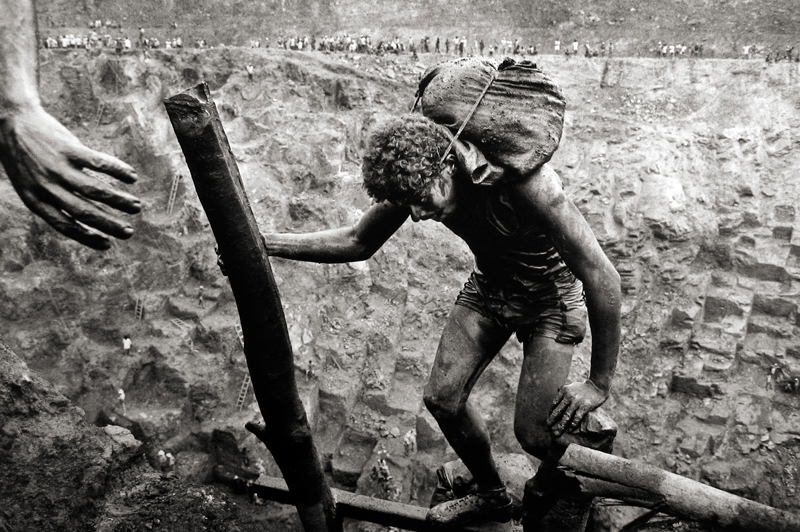

PF: I think it was about 23, 24 years ago. I started to look at the work. I think it was 1984 when the New York Times published Salgado's “Gold Mine series”. I think when I saw that Figure 8 print, that was a remarkable experience for me. Because who could believe something like this was going on in the times in which we’re living. It looks totally medieval. It looks like these people are just building the pyramids. So, the human condition ant-like. I mean, it’s an extraordinary image.

AF: That series also, when I first saw it, was extremely moving to me. I never forgot it either. The one image of the young miner holding the muzzle of the guard’s machine gun, his determination and courage to do that... The recorded physicality of the men and how he (Salgado) just brought you into their world, and Salgado’s personal vision. We can talk more about his vision later, but there are so many things I want to ask you about Salgado. What do you personally find so important about his work? I know you have such great respect for what he’s accomplished in his life.

PF:

PF: Well, he has enormous commitment and enormous passion. When you’re around him, he just communicates that and it inspires you. It pushes you to limits of (SIGH)... It pushes you to do the best you can do. Because, in a way you’re serving someone who has a real gift and who is a real master. It’s inspiring to be around people like that. Somebody who is greatly positive, who is so focused, who is so dedicated, who doesn’t complain, who doesn’t badmouth anybody, but just does it. That’s inspiring.

AF: Yes... Right... and I was wondering, because I know there’s a period in his life-that he came from a country that was horribly corrupt politically, the military was killing their own citizens, local opposition leaders would just disappear from sight, there was a dictator in charge at the time in Brazil (Salgado’s home country). I guess at a certain point in his own life, he decided it was best for him to leave or face unimaginable circumstances including being murdered by the regime.

PF: He had to leave. He is a committed anti-government person. He saw what was going around in this corrupt regime, and had to leave. Otherwise, he’d be killed.

AF: Sadly during that time a typical Latin American situation. If you look at Juan Peron in Argentina or Anastasio Somosa in Nicaragua... they all had death squads.

PF: Yes... death squads. The disappeared people. We take so much for granted here. I mean, we can walk down the street without being kidnapped or shot or killed, hopefully, by a government agent.

AF: But I was wondering something about that. Do you think artists that come from countries that are so oppressive... because Josef Koudelka also grew up under an oppressive Communist regime in Czechoslovakia, different then the oppressive government of Brazil, but still quite harsh. Do you think it gives them more of an appreciation for the right to express themselves freely as artists? When they finally break away? To visually be able to explore their world without fear of death or imprisonment, to make their statements from the heart?

PF: It must instill in you something. I mean, it instills in you humanity, a respect for people, a respect for life. So Yes... it gives you a freedom. It gives you incredible creative freedom. You want to tell a story. I think everything is motivated by some kind of advocacy, especially in

Sebastião’s work.

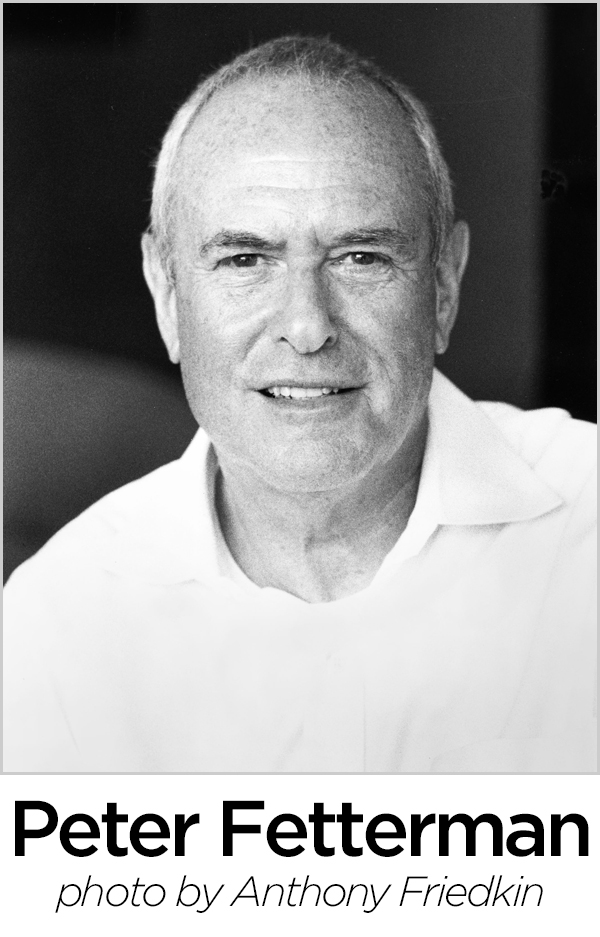

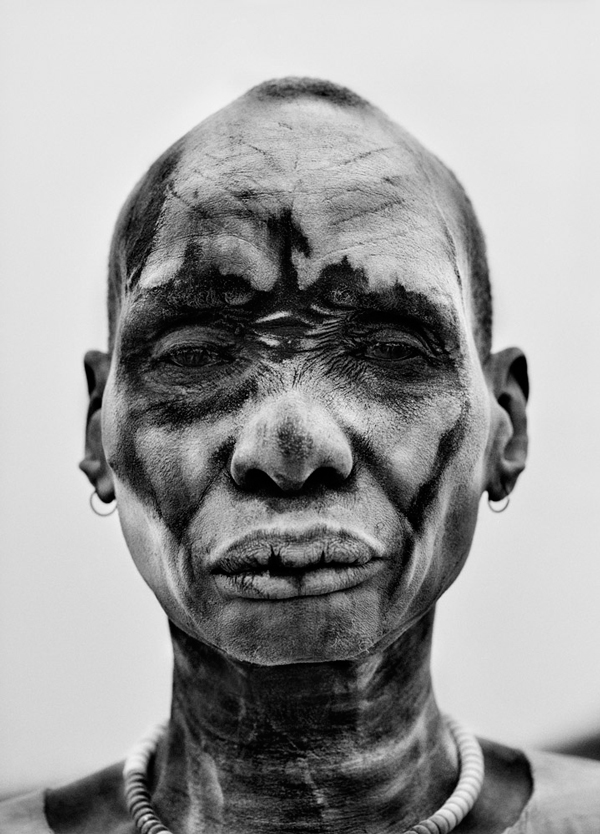

[caption id="attachment_2696" align="aligncenter" width="600"]

© Sebastiao Salgado / Amazonas Images[/caption]

AF: I was thinking about...

PF: Spread the word. Tell the truth. I mean, writers tell the truth. Sometimes they are put in prison for it or killed for it- shot for it, or put out into some gulag in Siberia. We’re talking about our lifetimes, the large number of dissidents who were tortured, killed.

AF: How does

Sebastiao

Salgado, the artist, (you think) see himself? Because most of what he talks about in his lectures, and he’s such a concerned and committed activist, he speaks about the environment, humanity, and culture. He rarely refers to himself as an artist. However I was wondering, on the Fine Arts side of photography, here’s a man that has an extraordinary eye, a phenomenal eye, I think one of the things that I personally respond to so strongly about his work is his keen sense of light, which is fundamental for any great photographer to understand. His awareness of light is extraordinary, his sense of the decisive moment also, in my mind, is right up there with Cartier-Bresson’s actually. But I was wondering about your own personal observations. How would you compare Salgado’s work to Bresson’s work for example?

PF: Well, I don’t think he considers himself an artist. I think that term is put on him by other people. I think he considers himself a storyteller, a photographer, as somebody who has a mission to tell stories and explain the world to us.

AF: Of course, you see him as an artist. In your own mind, you see him as an artist.

PF: I mean, I think you cannot do that kind of consistent body of work over 40 years, and with that quality of the work, unless you have a special gift. I mean, everybody can be a composer. Everybody can be a writer, but there are very few Mozarts and there are very few Dickenses or Hemingways or whatever. I mean, everybody wants to be everything. The technology allows everyone to be everything.

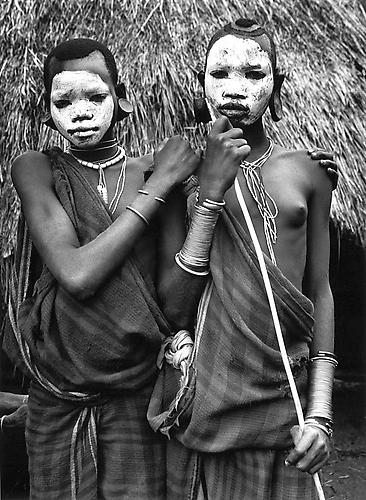

[caption id="attachment_2684" align="aligncenter" width="600"]

© Sebastiao Salgado / Amazonas Images[/caption]

AF: It’s just kind of a dangerous area, I think, to try to talk about photo journalism in the art of photography. When does a document, like the classic sense of the narrative document in photography, become a work of art? How does it suddenly transcend to being more than just a document of a time and a place? It somehow speaks to much higher levels of...

PF: I think it affects people emotionally. I think it changes people. You are one person before you are exposed to that piece of art, and you’re another person afterwards. That to me has always been the definition of what makes something great. What makes a great novel? A lot of novels-there’s probably 2,000 published every month-but what makesMadame Bovary

or

Crime and Punishment, or whatever the novel is. You’re haunted by it. It’s something that becomes part of you that you can’t forget. So, the thing about Salgado is, you can’t really forget these photographs. The fact that we’re still talking about them thirty years after they’ve been created and will be talking about them. They’re in the history books. So, that’s what distinguishes him from every other person. Other people may take one or two good photographs in their career. I mean, truly good ones. But, to consistently-I suppose in baseball terms-hit the home run every-so many times. There has to be some God-given talent.

AF: Don’t you also think part of his extraordinary commitment to his vision is his patience to stay with the story, to get to know the people? Can you talk a little bit about that?

PF:

PF: I think, for example, let’s go back to the famous Gold Mining series. Salgado wasn’t the first photojournalist to hit upon that specific gold mine in Northern Brazil. I think other photojournalists had been there. They had been there for a day. They took a shot. They leave. He, because of his training as an economist, was fascinated by the whole infrastructure. He understood the story. He became one of those people. I believe he didn’t take a photograph for several weeks until he really understood what was going on. He became anonymous. He became one of those miners. He ate with them.

AF: Yes. But, even in the selections you’ve made from

Genesis, that you now have currently hanging in your gallery, the work that he did with the native Siberian Eskimo population the “Nenets” in Russia, Salgado showed the same type of commitment, right? He stayed there for a very long time and became part of the tribe so to speak, gained their confidence and documented their daily routines and rituals.

PF: Absolutely. He was there for three months in the freezing cold in the middle of Siberia becoming one of these people. As I think I told you the story earlier, he was there with a lot of expensive outerwear gear on him. He was freezing cold. He couldn’t work. Even that, it was so cold that his clothing couldn’t protect him, the natives, the Nenets made a fur coat for him, which allowed him to become one of them, to sustain himself with them, and able to work. That’s a degree of dedication and commitment that very few people would put themselves through.

AF: But, it also shows how, on a trust level, the people that he works with have faith in him. That’s so important. I mean, it’s everything for a photographer to have the trust of the people that he’s working with. Especially some kind of a subculture where you don’t really understand these people’s lives and you’re asking them to let you photograph their undisclosed personal moments.

PF: He can’t communicate with them by language. He has to communicate with them by empathy. He becomes one of the people that he’s photographing because he understands their story. That’s why it works. I mean, no one’s paying him to do this. He’s not on assignment. No one has assigned him to do this. I mean, what he’s brilliant about is, because of his training as an economist, is he’s able to mobilize the resources that will enable a project like this to even materialize. Now, that’s a special talent as well.

AF: If I understood him correctly in the lecture that he gave at the Hammer Museum a few years ago, he said that he felt that his background, by being an economist and being, in a certain sense, from academia, that it gave him a perspective different than if he had grown up in the art world.

PF: Well, he understands the real world. I think to be a really great artist, a great photographer, you’ve got to have a broader understanding of the world we live in, rather than just some specific subject. That’s because it helps you to interpret it for other people, to communicate it.

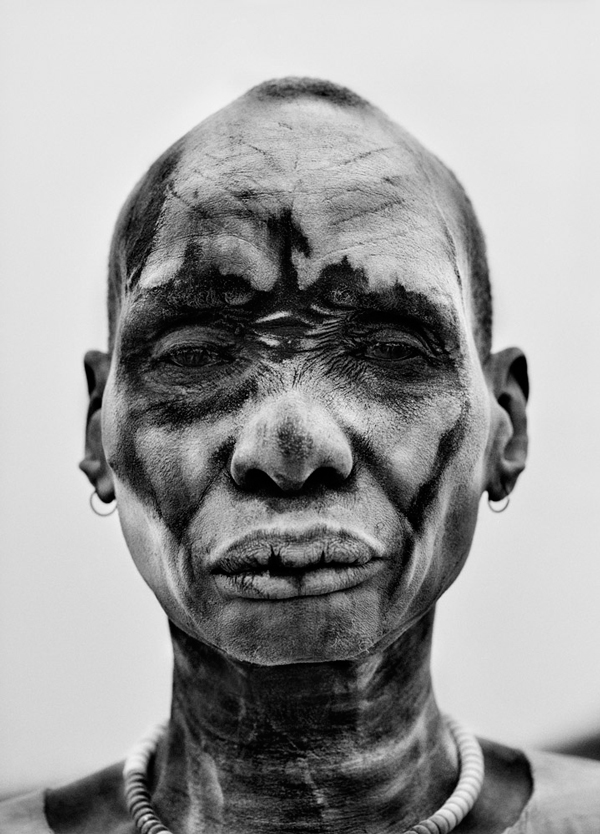

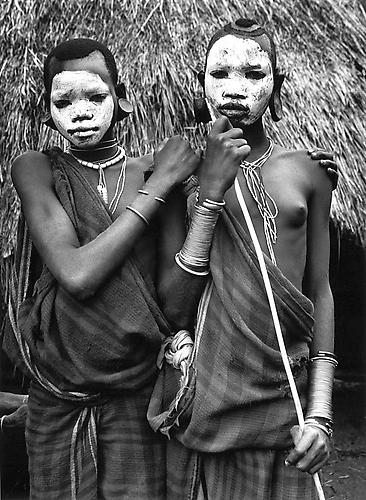

[caption id="attachment_2685" align="aligncenter" width="600"]

© Sebastiao Salgado / Amazonas Images[/caption]

AF: Referencing that to his project

Genesis, a project dedicated to showing the beauty of our planet, reversing the damage done to it, and preserving it for the future, I’m assuming he’s still passionately committed to its conception, and in a sense his life’s work has really been committed to it.

PF: He tends to do these eight- to ten -years epic projects.

Genesis is the last of them, the most recent of them.

AF:

AF: So, do you think he’s been successful in that so far? In the sense of trying to get people to elevate their awareness of what the earth is really about? The magnificence of the earth, to preserve certain cultures, to preserve... There’s the whole history of the “Concerned Photographer” going way, way back, before Salgado, with early 20th century photographers like Jacob Riis and Lewis Hine doing remarkable work, and later photographers like Eugene Smith or the Magnum photographers, Werner Bischoff, Robert Capa and people like them, made an effort to try to make it a healthier world by showing you human conditions that needed to be changed, but they also made visible through the art of photography various elements of our planet that needed to be preserved and appreciated.

What I’m wondering is, and this is a tough question again because, there’s been a huge history of photography’s efforts to make our world a better place to live in, to make it a more loving place to live in, to be more respectful of the gifts of the universe, everything that we hold dear to us as human beings. Has

GENESIS been successful in that admirable pursuit?

PF: Well, he’s done this. But he’s done this also allied with a very pragmatic application of it. So, he set up this rain forest project called Institute de Terra. This is an area of land that he grew up in. When he grew up in it, it was pristine. He was surrounded by beauty. He was surrounded by a nurturing nature. Of course, that’s all being ruined, destroyed now. So, what he’s done, he’s managed to raise the money and show the world what we can do. So, he’s planted single-handedly, he and his wife, two million trees and re-forested this area in which he grew up.

AF: Is it true that his family asked him to more or less take over the farm where he grew up?

PF: Yes. He grew up on this farm. He’s the eldest; he’s the only son in the family. It was agreed that he would have this farm and try and save it, and try to save the area, which he was doing. He’s managed to do that. So, not only does he put himself in these extreme situations to actually photograph as “an artist,” but then he takes what he’s learned and then, with another part of his brain, figures out how to plant two million trees and what it takes to do that, which is an incredible other energy level.

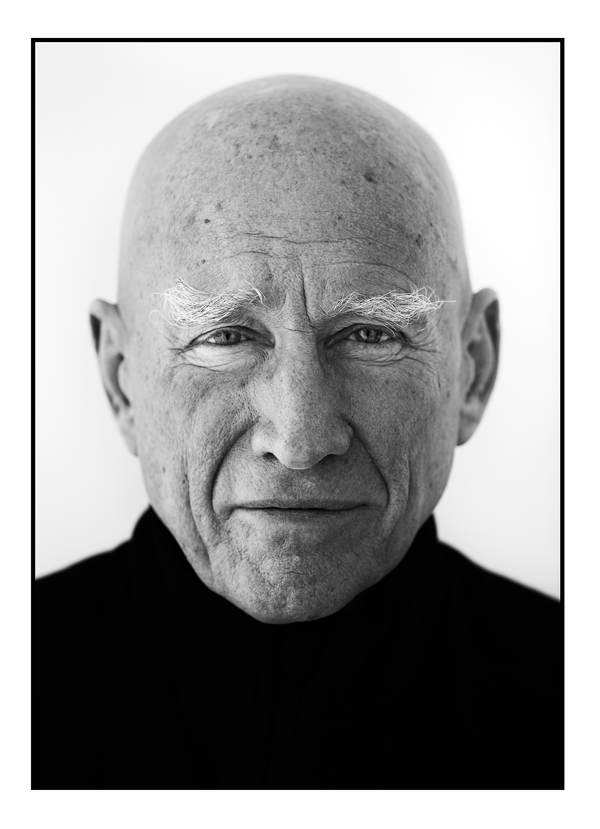

[caption id="attachment_2695" align="aligncenter" width="600"]

© Sebastiao Salgado / Amazonas Images[/caption]

AF: Right... But his wife, it seems, is very helpful to him in accomplishing these goals...

PF: Oh, his wife is...

AF: And they’ve been married a really long time.

PF: They’ve been married for 40 years. She’s a trained architect. She’s a trained graphic designer. She’s a very practical hands-on partner. He admits without Lélia, he would probably never have been able to achieve any of these projects. So, it’s lucky that an artist has a great person who they can trust and stands behind them and helps them. They’re a wonderful couple in tandem.

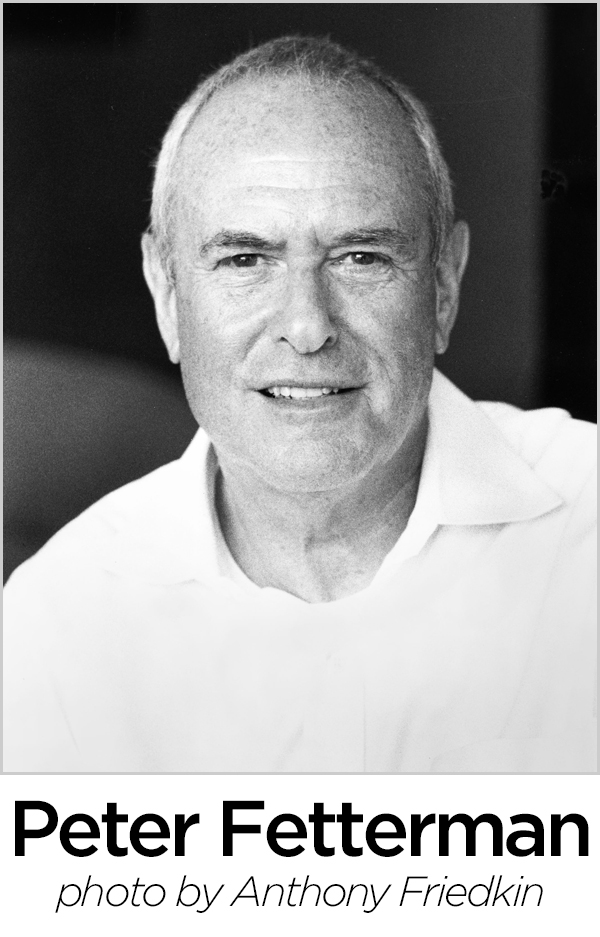

[caption id="attachment_2694" align="aligncenter" width="600"]

© Sebastiao Salgado / Amazonas Images[/caption]

AF: I read he was quoted as saying, “I hope that a person who visits my exhibitions and the person who comes out are not quite the same.” What do you think he meant by that, in his terms?

PF: He means that you now respect the land. You respect humanity. You change your behavioral patterns, because he helps us to connect... That’s what’s really powerful about an artist like Sebastião Salgado If you can connect with a lot of people and change their behavior, hopefully.

AF: Why do you think he continues to work in black and white?

PF: Because it’s more real for him. He’s telling a story. He realizes that that’s his gift. If you were to take the same image in color, it wouldn’t have the same impact. Can you imagine seeing a movie like Raging Bull now in color? It just wouldn’t work.

[caption id="attachment_2690" align="aligncenter" width="600"]

© Sebastiao Salgado / Amazonas Images[/caption]

AF: Right, right... But it’s interesting because he’s very connected to reality, what’s going on with our planet, that he has chosen, in a way, to show his incredible respect for this in black and white, which actually abstracts reality. It’s more of an abstraction of reality.

PF: It creates a power.

AF: Yes. But it’s interesting, from the artistic standpoint, in my mind, that he’s been very dedicated and pure about his vision by staying in black and white, especially now with all the new technology in digital.

PF: So, in a way he’s a throwback. I mean, he’s a classical black and white photographer in the tradition of Bresson or Strand, or Ansel Adams. Can you imagine Ansel Adams’ photographs all in color? His most celebrated, iconic images.

AF: Well, no, but Adams did actually explore color and shoot color, as did Weston, and even Bruce Davidson, who is a great street photographer.

PF: Yes, Subway series, absolutely.

AF: I mean, some of them do decide to go to color a little bit occasionally. Gordon Parks, I think, did a beautiful series of work in color.

PF: Yes. And Ernst Haas did his best work in color. I think everybody realizes what their instrument is as an artist, what’s their best instrument, their best...

AF: Is Salgado very good at editing his own work?

PF: [PAUSE] That’s a tough question.

AF: Well, a lot of people feel photographers are very bad at editing their own work. I mean, I’ve spoken to a number of curators in museums, and people like yourself, that have worked around photographers and sold photography for a long, long time. Many of them feel that photographers are not necessarily always their best own editors.

PF: I would go along with that.

Q:You would?

PF: I would. I mean, not to take anything away from the person who creates the work, but it’s true of writers. I mean, why do a lot of great writers have great book editors? They work with their publisher. There’s a book editor who they collaborate with. [SIGH] I think there is a degree of collaboration. You can get too close to it.

AF: Now, you made the selection yourself of what you have of Salgado’s work, here in your gallery exhibit, correct?

PF: Correct.

AF:

AF: So, can you talk about the process that you employed? Did you go with just gut instinct about these pictures... which ones really moved you? Or, did you think in terms of...

PF: Yes. I mean, that’s the only way I go. I mean, [SIGH]. There are 400 images in the big Genesis shows, which are playing now in Rome, in London, in Rio.

AF: Do you think that’s too many possibly? I mean, do you think that’s almost too much for people to be able to absorb?

PF: I can only say on a personal level. I remember some of the earlier Epic projects. I had to keep going back and back just to take them all in. I think that there is a point of saturation in terms of attention, in terms of digesting the subject matter. There’s that phrase, less is more. So, given that my square footage in my gallery isn’t as extensive as the Natural History Museum in London. So, I had to edit. So, I go on what are the images that blow me away. I had to prioritize. For example, you see a whole wall of the Nenet series, of Russia, the Russian Eskimos. That to me is one of the strongest parts of Genesis, but that’s a personal [PAUSE] taste. When you run a gallery, you’re doing it because you want to fulfill your own kind of [PAUSE] dreams, or tastes, or choices. That’s what gallery owners do for the most part.

AF: How do you decide, or do you decide with him, on pricing? How do you decide for example how one photograph is necessarily more expensive than another photograph?

PF: I must say, because Sebastião is a trained economist, he has a sense. I mean, he sets the prices, not me. Of course, there have been times when I say, “I think maybe they are too low or too high.” So, he takes that guidance, but it’s his decision, as it is with most artists. So, if certain images seem to be more appealing to people, then maybe that’s an economic signal to maybe price them a little bit higher. There again, most artists want people to appreciate more than their [PAUSE] top five images.

AF: Of course...

PF: So, if you price your top five images higher, maybe that brings more people to some of your other images, which are equally as good. I mean, none of this is a science. I mean, pricing is not a science.

AF: True.

PF: It’s irrational in many respects. Some of my favorite images from his body of work are also the lesser priced ones. So, there’s no equilibrium between higher price, more quality. I think it’s a ridiculous concept when you’re talking about art.

[caption id="attachment_2687" align="aligncenter" width="600"]

© Sebastiao Salgado / Amazonas Images[/caption]

AF: Have you ever seen any, what we might call, a very private set of photographs that he has created about his own personal life? Either photographs of his wife, or-does he have any children?

PF: He does. He has two sons. One of his sons is severely handicapped, has Down ’s syndrome. I think a lot of his general empathy for humanity, for the kind of work he does, I’m sure must stem from this. I mean, as a parent, I can’t imagine anything more heartbreaking than to be a parent to a child that has [PAUSE] disabilities. I think, on a strictly pure one-on-one human level, what that does to you as a human being certainly opens your heart or your sensitivity [PAUSE] exponentially. I think a lot of the work that he’s created, the heartbreakingly empathetic work has to be some kind of personal working out, understanding, empathy of what you go through as a parent.

AF: What kind of a person is he to be around?

PF: He’s a very positive, he’s very high energy, incredibly focused, incredibly intelligent, can read a situation and act on it immediately.

AF: He is a self-taught photographer, correct?

PF: Yes, he was an economist. His wife one day gave him-he picked up his wife’s camera and he started to play with it and take photographs.

AF: He’s extremely technically adept. I mean, his gelatin silver prints are magnificent. One can’t make great prints like that unless one creates excellent negatives in the first place.

PF: Well, he has an incredible intellect. So, he learns. I mean, he studies and he learns. He tries and he experiments. He’s auto didactic. I mean, he’s on a mission. The mission is to create this work that explains the First World to the Third World, or the Third World to the First World. I mean, we’re all connected. That’s the basic principle of his work.

AF: I thought the way he discussed the human being, as an animal was very interesting.

PF: Well, we’re very similar. He said to me, “Peter, no, no picture of just two lions. They are brothers.” He’s right. We’re all the same. We all want the same things. We want a place to live. We want enough food to eat. We want some kind of warmth. We’re all the same.

AF:

AF: A personal observation I would like to bring back into the conversation is that the way his social activism is respected, (and rightly so), it’s difficult for me not to also acknowledge his extraordinary artistic ability. This man has an amazing eye. I mean, every once in a while, there are some of his photographs that will absolutely stop me dead in my tracks. It’s noble to say that you’re an activist, and that you’re employing an art form as part of your activism. No one would deny that about his work as a photographer. But I see a whole other side of his work that is absolutely extraordinary, that goes beyond, in a sense, the document, or the social cause image, hopefully to make a better world for us. I actually think, whether his talent is a gift or not, his photographs are absolutely incredible and some of his best represent the artistic power the medium of photography can offer -like no other art form can.

PF: In the way that most of Mozart’s music is incredibly sublime, how can someone create this music? What state of mind do you have to be in? To be able to pour out that emotion and communicate it to masses of people forever? That’s the real gift.

AF: And to be prolific too.

PF: Yes... and to keep on doing it. Beethoven was doing it when he was deaf. I mean, that is an incredible talent that very few people have. But, you have to have-you can learn technique, I’m assuming one can.

AF: Up to a point... it's never been an end in itself...

PF: Up to a point. You can be taught things up to a point. But, at the end of the day, it’s a gift that separates one group of artists from another group. I mean, look at Picasso. The range of subjects, the range of mediums, the longevity of that career. I mean, a lot of very creative people maybe have a very finite period where they were at the top of their game. It may last two years, five years. But, when it lasts 40 years or 50 years, there’s something...

AF: How do you contrast somebody like Robert Frank with Salgado? In your own mind?

PF: I think Robert Frank had, at a particular point of his life, a particular view. Maybe it was a five-year period. It was a specific subject. I mean, I think “The Americans” is a very interesting body of work. But, [PAUSE] it’s a finite period of work. It doesn’t go over 50 years, or 30 years, or 40 years. You look at the work from Nova Scotia and you look at the films, and you think, Okay. I don’t bow down in front of Robert Frank the way many people...

AF: Well, don’t you think he brought the blues to black and white photography?

PF: I think it’s an interesting take on America. I think there’s an objectivity coming from a country like Switzerland and to be thrown into this surface of America and to see the sadness of it, at its core.

AF: Right, in The Fifties, the Cold War.

PF: In the fifties. I think it’s a very interesting body of work. It’s great. But, did he have a 30-year career of doing as great a work as that? No.

AF: Why?

PF: It was a short moment of time for him.

AF: So, you come back to the idea that Salgado prefers being more the narrator, more the narrative storyteller.

PF: I think he’s driven by this inner passion, which you have or you don’t have, and this incredible empathy, an incredible desire to change. Not in a didactic sense, but as a human being, to open us up, to be aware, to respect.

AF: Do you have faith people will become more sensitive to the dramatic issues he’s presented us with? Because I know how he talks about atomic energy and the threat to the total earth through the atomic bomb. He’s obviously a very educated man with a deep knowledge of human history. Do you think he works out of any sense of anger, or bitterness, about his fear that we could blow it all and just screw everything up?

PF: I think essentially, he’s an optimist. I think he’s almost romantic. Whatever we do to each other as a species, whatever terrible acts that we create and inflict on each other, there is still hopefully somewhere in the world a basic human goodness. That’s what this project is about. That is our wake up call. That’s what

Genesis is about. We’ve destroyed 56% of the world’s natural resources as a species. We’re just indifferent, insensitive, greedy, vile, human beings to do this to something precious. But there is still 44% of it left. Hopefully, through the power and strength and beauty of these images, we will hopefully change. I mean, he changed it for himself in where he was born. He’s created this now new idyllic paradise, which was destroyed. So, if he can do it and plant two million trees, why can’t... And he set up a foundation and it’s a pilot study for other people from all over the world to go and see

Institute de Terra and see what he’s done and hopefully go back to their own communities and do the same for them. So, it’s a very optimistic, romantic, hopeful, positive thing.

AF: But, also, it’s the influence he might have on young photographers...for them to be inspired, to go out and try to make statements about their own personal feelings about the environment and culture.

PF: Absolutely.

AF: Do you think it has been a conscious decision of his to not, in a sense, throw himself in a war zone the way James Nachtwey has? Or, do you think there have been moments of human darkness...things he’s photographed that he has said to himself, “I don’t want people to know this happens. I don’t want people to know human beings treat each other like this. I don’t want to show...”

PF: No, he’s done that. He’s done that. He was in Rwanda. He’s seen those atrocities. He’s documented those atrocities.

AF: I haven’t seen much of that work then.

PF: I mean, absolutely. He’s seen people dying in front of him and documented that. From the series of the Sahel. I mean, there’s a father carrying his dead child. It’s incredibly powerful. So, he’s been there and he’s done it. He has seen that side of [PAUSE] incredible cruelty, incredible desperation, but he’s managed to come through it and survived it, and still believes...

AF:

AF: He’s an extraordinary optimist.

PF: I mean, that’s an incredible power and a gift. Most people would have given up. Most people would say, “I can’t do this. I can’t handle this. It’s all futile.” But he’s got this human resilience. I mean, we are hopefully a species that can survive whatever extreme is put on us, whatever extremities we are pushed through. I mean, there are people who came out of Auschwitz and survived and led productive lives.

AF: Hugely...

PF: Hugely productive lives, and influenced other people. What is Elie Wiesel about? I mean, the human spirit is strong. It’s sad that, on the one hand, you have incredible vile-Hitler, Stalin, incredible people-and you have Mother Teresa and you have someone like Salgado or Gandhi. I mean, there’s good and there’s bad.

AF: He’s been spoken of as a Gandhi with a camera, right?

PF: He would be embarrassed by that. But, you have to respect that and admire that and serve it.

AF: But for me, it’s not only this extraordinary dedication that he has, because other photojournalists can share in that dedication. They’ve led dedicated lives. They’ll go to war zones and dangerous areas. They can appreciate Yosemite Park as much as anybody and try to come up with an image that has spirituality to it. But to have the combination that Salgado has, with this extraordinary dedication to making the world a better place, getting us to recognize our potential. But he also has an amazing personal eye. I feel, myself, the thing that defines a great photographer, more than anything else, is their eye.

PF: Yes.

AF: I was wondering about the size of Salgado’s photographs displayed in your gallery. For example, is the size of an image something you’ll discuss together? Or, does he say, “Peter, I want this print to be this size, and not that size.” Or, do you make those decisions?

PF: I choose the images that I feel communicate to me the most- in the sizes that they communicate to me.

AF: So, then generally speaking, you choose. When you request a print from him, you will request that print in a certain size?

PF: I mean, he’s not dogmatic and says, “Peter, you can only have this print in this size.” No, he’s very collaborative in that sense of [PAUSE] allowing me to curate my own show. He’s secure enough to do that.

AF: But when he does his major exhibitions with the museums, like in London and Rome, does he give the curators the same autonomy ?

PF: No. Together with Lélia his wife, I think they design the shows. They’re given the specs of this is the space where we want to host your show. They very carefully design the shows for the museum.

AF:

AF: Do you feel that he’s ever expressed an interest in going into filmmaking as a documentary filmmaker? Has he ever gone outside of his comfort zone being a brilliant still photographer?

PF: I don’t think he has the desire to do that. He knows that, I think, filmmaking is a very collaborative process, especially in terms of the economics of the film business and the marketing aspects of the film business. I mean...

AF: It’s a whole other universe.

PF: It’s a whole other universe. You have to be blessed by so many people. When somebody gives you $50 million to make a movie, it comes with strings attached.

AF: Oh, of course.

PF: I don’t think he’s...

AF: I was thinking more in the documentary sense than dramatic films. You’ve known him almost 30 years now?

PF: 25 years.

AF: Have there been any hidden wonders or pearls of wisdom that you’ve realized after these 25 years of collaboration? Have any surprises come to you over all these years in terms of understanding his work on a deeper level, or knowing him?

PF: I’m surprised at the longevity of it. I’m surprised at the stamina of it. That it keeps going, and will keep going. I think, when you say somebody is a force of nature, which has almost become clichéd now, I think he is. I think he’s got incredible energy and spirit.

AF: How do you think the photography world will ultimately see his position in history?

PF: I think he’s one of the most important practitioners of this medium. I think he’s up there with Stieglitz and Cartier-Bresson and Strand and Eugene Smith. I think he’s one of a handful of truly gifted Mozarts.

AF: We’ve talked on and off over the years, comparing Josef Koudelka to Salgado. I know you’re also a big fan of Koudelka...

PF: Love Koudelka’s work.

AF: I am greatly inspired by Koudelka’s work. But you said to me something very interesting once, that Koudelka was-and I don’t want to misquote you if I use it-but it was something like “Koudelka’s photographing his dreams”. It’s a different playing field that Koudelka is working with, in some ways than Salgado’s. You felt Salgado is more tied to reality then Koudelka, if I recall correctly.

PF: I think maybe Koudelka’s canvas or focus is more contained. I think the range of the subjects that Salgado embraces is possibly larger. I mean, but this is not a competition.

AF: Exactly....each is a visionary in their own right. They’re probably friends.

PF: They are both extraordinarily gifted, great, great photographers. Almost in a way, who’s better: Mozart or Beethoven? It’s when you get to that level of “giants”.

AF: It’s something almost Kafkaesque for me about Koudelka’s work. He has gone on to, or into another area of exploration as a photographer, a different psychology, different than Salgado in some way.

PF: They’re both quite great artists. They’re both great photographers, but there is something about Sebastião’s ability to negotiate the real world.

AF: Right. That’s what I think you were talking about.

PF: I mean, I think to be able to fulfill. It’s okay to have a vision. A lot of great, creative people have visions. But then what stops them is the inability to translate that vision on strictly practical terms to get it done. I mean, this man is in a way like David Lean. He’s making epic projects, but he’s doing it almost single-handedly. That’s another level of commitment, talent, whatever you call it, that very few people have.

AF:

AF: How much does he scrutinize his prints?

PF: I think he’s very much hands on every single print.

AF: Has he been working with the same printer for a long time?

PF: Now that he’s started to make larger prints. I know that was a very difficult process for him. It took him years to find the right collaborators.

AF: Was it mostly in Paris where he worked?

PF: Mostly in Paris. So, he’s very technically savvy. He knows how to bring the best out of [PAUSE] everybody around him. He’s charismatic. He’s demanding, but he’s collaborative. I mean, that’s a real talent as well.

AF: Yes. Unbelievable.

PF: To know what you’re good at, what you’re bad at, and whose help you need? I mean Cartier-Bresson is the same. Bresson never went into a darkroom after 1937. So, he found printers who could interpret his own negatives better than he could. That’s humility to be able to admit what you’re good at and what you’re not good at and bring together the team that can raise your game. That’s talent.

AF: And a negative is like a screenplay. It needs interpretation. It has to be brought to life. As you know, you can print negatives so differently, it can make all the difference in how the audience experiences your photographs.

PF: So, to see him dialog with his printers is also extraordinary...

AF: Has he photographed very much in America? In the United States of America?

PF: Well, you can see some of it in

Genesis. The Colorado images, the Alaska images are some of the best work in

Genesis. So, yes. He took the shot of Reagan being shot. You remember that?

AF: OH... That’s right.

PF: That’s a very famous photograph. He was a working photojournalist.

AF: So now he and his wife are taking full responsibility for his whole archive?

PF: They have become autonomous.

AF: That’s incredible. Have you ever watched him go over his contact sheets?

PF: I have.

AF: How does he look at them, if I might ask? Does he use a magnifying glass when he looks at them?

PF: Yes. He looks in a loupe; he’s making notes; everything is carefully documented. I mean, he’s very hands on.

AF: He’s like an engineer.

PF: He’s a fanatic. He’s brilliant, I mean, in the way he perceives. I think physically, he’s now 68 years old. To keep doing this kind of work, walking the six days to find some remote village. He’s not being driven in a jeep. He’s literally walking to get to some place. I think, as any of us, as we all get older, the physical concerns become more apparent.

AF: Was he ever injured seriously on any assignment?

PF: He’s had some bad accidents. He’s had some near-escapes. He’s had some near-death escapes. Absolutely.

AF: Can you give me any examples?

PF: I believe he was in a plane crash. The plane he was in crashed. It’s a miracle he survived that. I think that’s probably the strongest...

AF: So, he’s a cat as well. He’s got nine lives on top of it all.

PF: He’s got nine lives. You have to. I mean, look. He’s been to every corner of the world seven times on this project, and put himself in extreme situations that you and I would just-any normal person would say, “Okay. No, I can’t do that. Enough”

AF: It’s too dangerous.

PF: There’s a very interesting documentary that has been shot by his son and Wim Wenders, which will be coming out at the end of the year.

AF: I can’t wait to see that.

PF: I’ve seen segments of it. It’s extraordinary. You understand what it takes to get these images. It will be a whole fresh insight into it .

AF: Is he able to discuss his process? I know he discusses his objectives very clearly about what he’s hoping to accomplish with his photographs. But, have you found him being able to, in a sense, open up and get more internal, personalize his process?

PF: He does a lot of research. He researches his subjects. He’ll know so much before he gets to any of these locations. He will have consulted anybody he can ask.

AF: Oh, really? That’s interesting.

PF: So, he goes in prepared, analytically prepared. He understands what he’s getting himself into. Of course, he’s open to surprises and changes, but he does his homework. He doesn’t just turn up at one of these remote locations without having done a lot of research.

AF: So, now he can travel freely to Brazil?

PF: He’s a god in Brazil. I mean, at his opening exhibition, the ex-president of Brazil flew 22 hours just to open his exhibition as a token of respect and friendship. That’s an extraordinary...

AF: Yes, that’s impressive for a photographer to be honored like that...

PF: He’s one-of-a-kind. I feel honored and proud that we’ve got the show.

AF: Well, I have a feeling he feels honored and proud that he has you.

PF: It's been a great marriage...

AF: Well, I will toast to you, Peter. Thank you very much for sharing your insights today...

The Sebastião Salgado GENESIS Exhibition runs through November 30, 2013 at the Peter Fetterman gallery

Sebastiao Salgado is a Brazilian-born photographer, who began his career as an economist. Today he is considered a living legend in the sphere of photography. He has committed himself to long-term projects, all of which are substantial in nature. He connects with his subjects on a deeply personal level, and is totally absorbed in black and white photography. His work is held in major museum collections worldwide and he is also credited with numerous photographic books. Recently he finished an impressive project titled GENESIS, the result of an epic eight- year expedition to rediscover the mountains, deserts, oceans, and the animals and peoples that have so far escaped the imprint of modern culture and technology.

Peter Fetterman is an internationally recognized Fine Art Photography dealer, and is currently exhibiting many of Sebastiao Salgado’s photographs from the project “GENESIS” at his gallery, which is located at Bergamot Station in Santa Monica. I had an opportunity to interview Peter about his long association and friendship with Sebastião Salgado to learn more about this exceptional photographer.

AF: Peter, before we get started, I wanted to personally congratulate you on your quarter of a century success and the dedication you’ve shown with your fine Photography Gallery located here in Los Angeles.

PF: Thank you... 25 incredible years...

AF: By bringing significant photography, both vintage and contemporary to the Los Angeles community and also by educating and supporting not only the collectors and engaging with them, but what you’ve done for the photographers you’ve exhibited through the years, the sales you’ve made on their behalf and by promoting the art of photography in general with such passion.

PF: It’s kind of you to say that.

Sebastiao Salgado is a Brazilian-born photographer, who began his career as an economist. Today he is considered a living legend in the sphere of photography. He has committed himself to long-term projects, all of which are substantial in nature. He connects with his subjects on a deeply personal level, and is totally absorbed in black and white photography. His work is held in major museum collections worldwide and he is also credited with numerous photographic books. Recently he finished an impressive project titled GENESIS, the result of an epic eight- year expedition to rediscover the mountains, deserts, oceans, and the animals and peoples that have so far escaped the imprint of modern culture and technology.

Peter Fetterman is an internationally recognized Fine Art Photography dealer, and is currently exhibiting many of Sebastiao Salgado’s photographs from the project “GENESIS” at his gallery, which is located at Bergamot Station in Santa Monica. I had an opportunity to interview Peter about his long association and friendship with Sebastião Salgado to learn more about this exceptional photographer.

AF: Peter, before we get started, I wanted to personally congratulate you on your quarter of a century success and the dedication you’ve shown with your fine Photography Gallery located here in Los Angeles.

PF: Thank you... 25 incredible years...

AF: By bringing significant photography, both vintage and contemporary to the Los Angeles community and also by educating and supporting not only the collectors and engaging with them, but what you’ve done for the photographers you’ve exhibited through the years, the sales you’ve made on their behalf and by promoting the art of photography in general with such passion.

PF: It’s kind of you to say that.

AF: Well, it’s true. It’s all true. I have a few questions about the current exhibition you’re hosting by photographer Sebastiao Salgado. So we might was well just jump right into it..... When did you first become aware of Sebastiao Salgado’s work?

PF: I think it was about 23, 24 years ago. I started to look at the work. I think it was 1984 when the New York Times published Salgado's “Gold Mine series”. I think when I saw that Figure 8 print, that was a remarkable experience for me. Because who could believe something like this was going on in the times in which we’re living. It looks totally medieval. It looks like these people are just building the pyramids. So, the human condition ant-like. I mean, it’s an extraordinary image.

AF: That series also, when I first saw it, was extremely moving to me. I never forgot it either. The one image of the young miner holding the muzzle of the guard’s machine gun, his determination and courage to do that... The recorded physicality of the men and how he (Salgado) just brought you into their world, and Salgado’s personal vision. We can talk more about his vision later, but there are so many things I want to ask you about Salgado. What do you personally find so important about his work? I know you have such great respect for what he’s accomplished in his life.

AF: Well, it’s true. It’s all true. I have a few questions about the current exhibition you’re hosting by photographer Sebastiao Salgado. So we might was well just jump right into it..... When did you first become aware of Sebastiao Salgado’s work?

PF: I think it was about 23, 24 years ago. I started to look at the work. I think it was 1984 when the New York Times published Salgado's “Gold Mine series”. I think when I saw that Figure 8 print, that was a remarkable experience for me. Because who could believe something like this was going on in the times in which we’re living. It looks totally medieval. It looks like these people are just building the pyramids. So, the human condition ant-like. I mean, it’s an extraordinary image.

AF: That series also, when I first saw it, was extremely moving to me. I never forgot it either. The one image of the young miner holding the muzzle of the guard’s machine gun, his determination and courage to do that... The recorded physicality of the men and how he (Salgado) just brought you into their world, and Salgado’s personal vision. We can talk more about his vision later, but there are so many things I want to ask you about Salgado. What do you personally find so important about his work? I know you have such great respect for what he’s accomplished in his life.

PF: Well, he has enormous commitment and enormous passion. When you’re around him, he just communicates that and it inspires you. It pushes you to limits of (SIGH)... It pushes you to do the best you can do. Because, in a way you’re serving someone who has a real gift and who is a real master. It’s inspiring to be around people like that. Somebody who is greatly positive, who is so focused, who is so dedicated, who doesn’t complain, who doesn’t badmouth anybody, but just does it. That’s inspiring.

AF: Yes... Right... and I was wondering, because I know there’s a period in his life-that he came from a country that was horribly corrupt politically, the military was killing their own citizens, local opposition leaders would just disappear from sight, there was a dictator in charge at the time in Brazil (Salgado’s home country). I guess at a certain point in his own life, he decided it was best for him to leave or face unimaginable circumstances including being murdered by the regime.

PF: He had to leave. He is a committed anti-government person. He saw what was going around in this corrupt regime, and had to leave. Otherwise, he’d be killed.

AF: Sadly during that time a typical Latin American situation. If you look at Juan Peron in Argentina or Anastasio Somosa in Nicaragua... they all had death squads.

PF: Yes... death squads. The disappeared people. We take so much for granted here. I mean, we can walk down the street without being kidnapped or shot or killed, hopefully, by a government agent.

AF: But I was wondering something about that. Do you think artists that come from countries that are so oppressive... because Josef Koudelka also grew up under an oppressive Communist regime in Czechoslovakia, different then the oppressive government of Brazil, but still quite harsh. Do you think it gives them more of an appreciation for the right to express themselves freely as artists? When they finally break away? To visually be able to explore their world without fear of death or imprisonment, to make their statements from the heart?

PF: It must instill in you something. I mean, it instills in you humanity, a respect for people, a respect for life. So Yes... it gives you a freedom. It gives you incredible creative freedom. You want to tell a story. I think everything is motivated by some kind of advocacy, especially in Sebastião’s work.

[caption id="attachment_2696" align="aligncenter" width="600"]

PF: Well, he has enormous commitment and enormous passion. When you’re around him, he just communicates that and it inspires you. It pushes you to limits of (SIGH)... It pushes you to do the best you can do. Because, in a way you’re serving someone who has a real gift and who is a real master. It’s inspiring to be around people like that. Somebody who is greatly positive, who is so focused, who is so dedicated, who doesn’t complain, who doesn’t badmouth anybody, but just does it. That’s inspiring.

AF: Yes... Right... and I was wondering, because I know there’s a period in his life-that he came from a country that was horribly corrupt politically, the military was killing their own citizens, local opposition leaders would just disappear from sight, there was a dictator in charge at the time in Brazil (Salgado’s home country). I guess at a certain point in his own life, he decided it was best for him to leave or face unimaginable circumstances including being murdered by the regime.

PF: He had to leave. He is a committed anti-government person. He saw what was going around in this corrupt regime, and had to leave. Otherwise, he’d be killed.

AF: Sadly during that time a typical Latin American situation. If you look at Juan Peron in Argentina or Anastasio Somosa in Nicaragua... they all had death squads.

PF: Yes... death squads. The disappeared people. We take so much for granted here. I mean, we can walk down the street without being kidnapped or shot or killed, hopefully, by a government agent.

AF: But I was wondering something about that. Do you think artists that come from countries that are so oppressive... because Josef Koudelka also grew up under an oppressive Communist regime in Czechoslovakia, different then the oppressive government of Brazil, but still quite harsh. Do you think it gives them more of an appreciation for the right to express themselves freely as artists? When they finally break away? To visually be able to explore their world without fear of death or imprisonment, to make their statements from the heart?

PF: It must instill in you something. I mean, it instills in you humanity, a respect for people, a respect for life. So Yes... it gives you a freedom. It gives you incredible creative freedom. You want to tell a story. I think everything is motivated by some kind of advocacy, especially in Sebastião’s work.

[caption id="attachment_2696" align="aligncenter" width="600"] © Sebastiao Salgado / Amazonas Images[/caption]

AF: I was thinking about...

PF: Spread the word. Tell the truth. I mean, writers tell the truth. Sometimes they are put in prison for it or killed for it- shot for it, or put out into some gulag in Siberia. We’re talking about our lifetimes, the large number of dissidents who were tortured, killed.

AF: How does Sebastiao Salgado, the artist, (you think) see himself? Because most of what he talks about in his lectures, and he’s such a concerned and committed activist, he speaks about the environment, humanity, and culture. He rarely refers to himself as an artist. However I was wondering, on the Fine Arts side of photography, here’s a man that has an extraordinary eye, a phenomenal eye, I think one of the things that I personally respond to so strongly about his work is his keen sense of light, which is fundamental for any great photographer to understand. His awareness of light is extraordinary, his sense of the decisive moment also, in my mind, is right up there with Cartier-Bresson’s actually. But I was wondering about your own personal observations. How would you compare Salgado’s work to Bresson’s work for example?

PF: Well, I don’t think he considers himself an artist. I think that term is put on him by other people. I think he considers himself a storyteller, a photographer, as somebody who has a mission to tell stories and explain the world to us.

AF: Of course, you see him as an artist. In your own mind, you see him as an artist.

PF: I mean, I think you cannot do that kind of consistent body of work over 40 years, and with that quality of the work, unless you have a special gift. I mean, everybody can be a composer. Everybody can be a writer, but there are very few Mozarts and there are very few Dickenses or Hemingways or whatever. I mean, everybody wants to be everything. The technology allows everyone to be everything.

[caption id="attachment_2684" align="aligncenter" width="600"]

© Sebastiao Salgado / Amazonas Images[/caption]

AF: I was thinking about...

PF: Spread the word. Tell the truth. I mean, writers tell the truth. Sometimes they are put in prison for it or killed for it- shot for it, or put out into some gulag in Siberia. We’re talking about our lifetimes, the large number of dissidents who were tortured, killed.

AF: How does Sebastiao Salgado, the artist, (you think) see himself? Because most of what he talks about in his lectures, and he’s such a concerned and committed activist, he speaks about the environment, humanity, and culture. He rarely refers to himself as an artist. However I was wondering, on the Fine Arts side of photography, here’s a man that has an extraordinary eye, a phenomenal eye, I think one of the things that I personally respond to so strongly about his work is his keen sense of light, which is fundamental for any great photographer to understand. His awareness of light is extraordinary, his sense of the decisive moment also, in my mind, is right up there with Cartier-Bresson’s actually. But I was wondering about your own personal observations. How would you compare Salgado’s work to Bresson’s work for example?

PF: Well, I don’t think he considers himself an artist. I think that term is put on him by other people. I think he considers himself a storyteller, a photographer, as somebody who has a mission to tell stories and explain the world to us.

AF: Of course, you see him as an artist. In your own mind, you see him as an artist.

PF: I mean, I think you cannot do that kind of consistent body of work over 40 years, and with that quality of the work, unless you have a special gift. I mean, everybody can be a composer. Everybody can be a writer, but there are very few Mozarts and there are very few Dickenses or Hemingways or whatever. I mean, everybody wants to be everything. The technology allows everyone to be everything.

[caption id="attachment_2684" align="aligncenter" width="600"] © Sebastiao Salgado / Amazonas Images[/caption]

AF: It’s just kind of a dangerous area, I think, to try to talk about photo journalism in the art of photography. When does a document, like the classic sense of the narrative document in photography, become a work of art? How does it suddenly transcend to being more than just a document of a time and a place? It somehow speaks to much higher levels of...

PF: I think it affects people emotionally. I think it changes people. You are one person before you are exposed to that piece of art, and you’re another person afterwards. That to me has always been the definition of what makes something great. What makes a great novel? A lot of novels-there’s probably 2,000 published every month-but what makesMadame Bovary or Crime and Punishment, or whatever the novel is. You’re haunted by it. It’s something that becomes part of you that you can’t forget. So, the thing about Salgado is, you can’t really forget these photographs. The fact that we’re still talking about them thirty years after they’ve been created and will be talking about them. They’re in the history books. So, that’s what distinguishes him from every other person. Other people may take one or two good photographs in their career. I mean, truly good ones. But, to consistently-I suppose in baseball terms-hit the home run every-so many times. There has to be some God-given talent.

AF: Don’t you also think part of his extraordinary commitment to his vision is his patience to stay with the story, to get to know the people? Can you talk a little bit about that?

© Sebastiao Salgado / Amazonas Images[/caption]

AF: It’s just kind of a dangerous area, I think, to try to talk about photo journalism in the art of photography. When does a document, like the classic sense of the narrative document in photography, become a work of art? How does it suddenly transcend to being more than just a document of a time and a place? It somehow speaks to much higher levels of...

PF: I think it affects people emotionally. I think it changes people. You are one person before you are exposed to that piece of art, and you’re another person afterwards. That to me has always been the definition of what makes something great. What makes a great novel? A lot of novels-there’s probably 2,000 published every month-but what makesMadame Bovary or Crime and Punishment, or whatever the novel is. You’re haunted by it. It’s something that becomes part of you that you can’t forget. So, the thing about Salgado is, you can’t really forget these photographs. The fact that we’re still talking about them thirty years after they’ve been created and will be talking about them. They’re in the history books. So, that’s what distinguishes him from every other person. Other people may take one or two good photographs in their career. I mean, truly good ones. But, to consistently-I suppose in baseball terms-hit the home run every-so many times. There has to be some God-given talent.

AF: Don’t you also think part of his extraordinary commitment to his vision is his patience to stay with the story, to get to know the people? Can you talk a little bit about that?

PF: I think, for example, let’s go back to the famous Gold Mining series. Salgado wasn’t the first photojournalist to hit upon that specific gold mine in Northern Brazil. I think other photojournalists had been there. They had been there for a day. They took a shot. They leave. He, because of his training as an economist, was fascinated by the whole infrastructure. He understood the story. He became one of those people. I believe he didn’t take a photograph for several weeks until he really understood what was going on. He became anonymous. He became one of those miners. He ate with them.

AF: Yes. But, even in the selections you’ve made from Genesis, that you now have currently hanging in your gallery, the work that he did with the native Siberian Eskimo population the “Nenets” in Russia, Salgado showed the same type of commitment, right? He stayed there for a very long time and became part of the tribe so to speak, gained their confidence and documented their daily routines and rituals.

PF: Absolutely. He was there for three months in the freezing cold in the middle of Siberia becoming one of these people. As I think I told you the story earlier, he was there with a lot of expensive outerwear gear on him. He was freezing cold. He couldn’t work. Even that, it was so cold that his clothing couldn’t protect him, the natives, the Nenets made a fur coat for him, which allowed him to become one of them, to sustain himself with them, and able to work. That’s a degree of dedication and commitment that very few people would put themselves through.

AF: But, it also shows how, on a trust level, the people that he works with have faith in him. That’s so important. I mean, it’s everything for a photographer to have the trust of the people that he’s working with. Especially some kind of a subculture where you don’t really understand these people’s lives and you’re asking them to let you photograph their undisclosed personal moments.

PF: He can’t communicate with them by language. He has to communicate with them by empathy. He becomes one of the people that he’s photographing because he understands their story. That’s why it works. I mean, no one’s paying him to do this. He’s not on assignment. No one has assigned him to do this. I mean, what he’s brilliant about is, because of his training as an economist, is he’s able to mobilize the resources that will enable a project like this to even materialize. Now, that’s a special talent as well.

AF: If I understood him correctly in the lecture that he gave at the Hammer Museum a few years ago, he said that he felt that his background, by being an economist and being, in a certain sense, from academia, that it gave him a perspective different than if he had grown up in the art world.

PF: Well, he understands the real world. I think to be a really great artist, a great photographer, you’ve got to have a broader understanding of the world we live in, rather than just some specific subject. That’s because it helps you to interpret it for other people, to communicate it.

[caption id="attachment_2685" align="aligncenter" width="600"]

PF: I think, for example, let’s go back to the famous Gold Mining series. Salgado wasn’t the first photojournalist to hit upon that specific gold mine in Northern Brazil. I think other photojournalists had been there. They had been there for a day. They took a shot. They leave. He, because of his training as an economist, was fascinated by the whole infrastructure. He understood the story. He became one of those people. I believe he didn’t take a photograph for several weeks until he really understood what was going on. He became anonymous. He became one of those miners. He ate with them.

AF: Yes. But, even in the selections you’ve made from Genesis, that you now have currently hanging in your gallery, the work that he did with the native Siberian Eskimo population the “Nenets” in Russia, Salgado showed the same type of commitment, right? He stayed there for a very long time and became part of the tribe so to speak, gained their confidence and documented their daily routines and rituals.

PF: Absolutely. He was there for three months in the freezing cold in the middle of Siberia becoming one of these people. As I think I told you the story earlier, he was there with a lot of expensive outerwear gear on him. He was freezing cold. He couldn’t work. Even that, it was so cold that his clothing couldn’t protect him, the natives, the Nenets made a fur coat for him, which allowed him to become one of them, to sustain himself with them, and able to work. That’s a degree of dedication and commitment that very few people would put themselves through.

AF: But, it also shows how, on a trust level, the people that he works with have faith in him. That’s so important. I mean, it’s everything for a photographer to have the trust of the people that he’s working with. Especially some kind of a subculture where you don’t really understand these people’s lives and you’re asking them to let you photograph their undisclosed personal moments.

PF: He can’t communicate with them by language. He has to communicate with them by empathy. He becomes one of the people that he’s photographing because he understands their story. That’s why it works. I mean, no one’s paying him to do this. He’s not on assignment. No one has assigned him to do this. I mean, what he’s brilliant about is, because of his training as an economist, is he’s able to mobilize the resources that will enable a project like this to even materialize. Now, that’s a special talent as well.

AF: If I understood him correctly in the lecture that he gave at the Hammer Museum a few years ago, he said that he felt that his background, by being an economist and being, in a certain sense, from academia, that it gave him a perspective different than if he had grown up in the art world.

PF: Well, he understands the real world. I think to be a really great artist, a great photographer, you’ve got to have a broader understanding of the world we live in, rather than just some specific subject. That’s because it helps you to interpret it for other people, to communicate it.

[caption id="attachment_2685" align="aligncenter" width="600"] © Sebastiao Salgado / Amazonas Images[/caption]

AF: Referencing that to his project Genesis, a project dedicated to showing the beauty of our planet, reversing the damage done to it, and preserving it for the future, I’m assuming he’s still passionately committed to its conception, and in a sense his life’s work has really been committed to it.

PF: He tends to do these eight- to ten -years epic projects. Genesis is the last of them, the most recent of them.

© Sebastiao Salgado / Amazonas Images[/caption]

AF: Referencing that to his project Genesis, a project dedicated to showing the beauty of our planet, reversing the damage done to it, and preserving it for the future, I’m assuming he’s still passionately committed to its conception, and in a sense his life’s work has really been committed to it.

PF: He tends to do these eight- to ten -years epic projects. Genesis is the last of them, the most recent of them.

AF: So, do you think he’s been successful in that so far? In the sense of trying to get people to elevate their awareness of what the earth is really about? The magnificence of the earth, to preserve certain cultures, to preserve... There’s the whole history of the “Concerned Photographer” going way, way back, before Salgado, with early 20th century photographers like Jacob Riis and Lewis Hine doing remarkable work, and later photographers like Eugene Smith or the Magnum photographers, Werner Bischoff, Robert Capa and people like them, made an effort to try to make it a healthier world by showing you human conditions that needed to be changed, but they also made visible through the art of photography various elements of our planet that needed to be preserved and appreciated.

What I’m wondering is, and this is a tough question again because, there’s been a huge history of photography’s efforts to make our world a better place to live in, to make it a more loving place to live in, to be more respectful of the gifts of the universe, everything that we hold dear to us as human beings. Has GENESIS been successful in that admirable pursuit?

PF: Well, he’s done this. But he’s done this also allied with a very pragmatic application of it. So, he set up this rain forest project called Institute de Terra. This is an area of land that he grew up in. When he grew up in it, it was pristine. He was surrounded by beauty. He was surrounded by a nurturing nature. Of course, that’s all being ruined, destroyed now. So, what he’s done, he’s managed to raise the money and show the world what we can do. So, he’s planted single-handedly, he and his wife, two million trees and re-forested this area in which he grew up.

AF: Is it true that his family asked him to more or less take over the farm where he grew up?

PF: Yes. He grew up on this farm. He’s the eldest; he’s the only son in the family. It was agreed that he would have this farm and try and save it, and try to save the area, which he was doing. He’s managed to do that. So, not only does he put himself in these extreme situations to actually photograph as “an artist,” but then he takes what he’s learned and then, with another part of his brain, figures out how to plant two million trees and what it takes to do that, which is an incredible other energy level.

[caption id="attachment_2695" align="aligncenter" width="600"]

AF: So, do you think he’s been successful in that so far? In the sense of trying to get people to elevate their awareness of what the earth is really about? The magnificence of the earth, to preserve certain cultures, to preserve... There’s the whole history of the “Concerned Photographer” going way, way back, before Salgado, with early 20th century photographers like Jacob Riis and Lewis Hine doing remarkable work, and later photographers like Eugene Smith or the Magnum photographers, Werner Bischoff, Robert Capa and people like them, made an effort to try to make it a healthier world by showing you human conditions that needed to be changed, but they also made visible through the art of photography various elements of our planet that needed to be preserved and appreciated.

What I’m wondering is, and this is a tough question again because, there’s been a huge history of photography’s efforts to make our world a better place to live in, to make it a more loving place to live in, to be more respectful of the gifts of the universe, everything that we hold dear to us as human beings. Has GENESIS been successful in that admirable pursuit?

PF: Well, he’s done this. But he’s done this also allied with a very pragmatic application of it. So, he set up this rain forest project called Institute de Terra. This is an area of land that he grew up in. When he grew up in it, it was pristine. He was surrounded by beauty. He was surrounded by a nurturing nature. Of course, that’s all being ruined, destroyed now. So, what he’s done, he’s managed to raise the money and show the world what we can do. So, he’s planted single-handedly, he and his wife, two million trees and re-forested this area in which he grew up.

AF: Is it true that his family asked him to more or less take over the farm where he grew up?

PF: Yes. He grew up on this farm. He’s the eldest; he’s the only son in the family. It was agreed that he would have this farm and try and save it, and try to save the area, which he was doing. He’s managed to do that. So, not only does he put himself in these extreme situations to actually photograph as “an artist,” but then he takes what he’s learned and then, with another part of his brain, figures out how to plant two million trees and what it takes to do that, which is an incredible other energy level.

[caption id="attachment_2695" align="aligncenter" width="600"] © Sebastiao Salgado / Amazonas Images[/caption]

AF: Right... But his wife, it seems, is very helpful to him in accomplishing these goals...

PF: Oh, his wife is...

AF: And they’ve been married a really long time.

PF: They’ve been married for 40 years. She’s a trained architect. She’s a trained graphic designer. She’s a very practical hands-on partner. He admits without Lélia, he would probably never have been able to achieve any of these projects. So, it’s lucky that an artist has a great person who they can trust and stands behind them and helps them. They’re a wonderful couple in tandem.

[caption id="attachment_2694" align="aligncenter" width="600"]

© Sebastiao Salgado / Amazonas Images[/caption]

AF: Right... But his wife, it seems, is very helpful to him in accomplishing these goals...

PF: Oh, his wife is...

AF: And they’ve been married a really long time.

PF: They’ve been married for 40 years. She’s a trained architect. She’s a trained graphic designer. She’s a very practical hands-on partner. He admits without Lélia, he would probably never have been able to achieve any of these projects. So, it’s lucky that an artist has a great person who they can trust and stands behind them and helps them. They’re a wonderful couple in tandem.

[caption id="attachment_2694" align="aligncenter" width="600"] © Sebastiao Salgado / Amazonas Images[/caption]

AF: I read he was quoted as saying, “I hope that a person who visits my exhibitions and the person who comes out are not quite the same.” What do you think he meant by that, in his terms?

PF: He means that you now respect the land. You respect humanity. You change your behavioral patterns, because he helps us to connect... That’s what’s really powerful about an artist like Sebastião Salgado If you can connect with a lot of people and change their behavior, hopefully.

AF: Why do you think he continues to work in black and white?

PF: Because it’s more real for him. He’s telling a story. He realizes that that’s his gift. If you were to take the same image in color, it wouldn’t have the same impact. Can you imagine seeing a movie like Raging Bull now in color? It just wouldn’t work.

[caption id="attachment_2690" align="aligncenter" width="600"]

© Sebastiao Salgado / Amazonas Images[/caption]

AF: I read he was quoted as saying, “I hope that a person who visits my exhibitions and the person who comes out are not quite the same.” What do you think he meant by that, in his terms?

PF: He means that you now respect the land. You respect humanity. You change your behavioral patterns, because he helps us to connect... That’s what’s really powerful about an artist like Sebastião Salgado If you can connect with a lot of people and change their behavior, hopefully.

AF: Why do you think he continues to work in black and white?

PF: Because it’s more real for him. He’s telling a story. He realizes that that’s his gift. If you were to take the same image in color, it wouldn’t have the same impact. Can you imagine seeing a movie like Raging Bull now in color? It just wouldn’t work.

[caption id="attachment_2690" align="aligncenter" width="600"] © Sebastiao Salgado / Amazonas Images[/caption]

AF: Right, right... But it’s interesting because he’s very connected to reality, what’s going on with our planet, that he has chosen, in a way, to show his incredible respect for this in black and white, which actually abstracts reality. It’s more of an abstraction of reality.

PF: It creates a power.

AF: Yes. But it’s interesting, from the artistic standpoint, in my mind, that he’s been very dedicated and pure about his vision by staying in black and white, especially now with all the new technology in digital.

PF: So, in a way he’s a throwback. I mean, he’s a classical black and white photographer in the tradition of Bresson or Strand, or Ansel Adams. Can you imagine Ansel Adams’ photographs all in color? His most celebrated, iconic images.

AF: Well, no, but Adams did actually explore color and shoot color, as did Weston, and even Bruce Davidson, who is a great street photographer.

PF: Yes, Subway series, absolutely.

AF: I mean, some of them do decide to go to color a little bit occasionally. Gordon Parks, I think, did a beautiful series of work in color.

PF: Yes. And Ernst Haas did his best work in color. I think everybody realizes what their instrument is as an artist, what’s their best instrument, their best...

AF: Is Salgado very good at editing his own work?

PF: [PAUSE] That’s a tough question.

AF: Well, a lot of people feel photographers are very bad at editing their own work. I mean, I’ve spoken to a number of curators in museums, and people like yourself, that have worked around photographers and sold photography for a long, long time. Many of them feel that photographers are not necessarily always their best own editors.

PF: I would go along with that.

Q:You would?

PF: I would. I mean, not to take anything away from the person who creates the work, but it’s true of writers. I mean, why do a lot of great writers have great book editors? They work with their publisher. There’s a book editor who they collaborate with. [SIGH] I think there is a degree of collaboration. You can get too close to it.

AF: Now, you made the selection yourself of what you have of Salgado’s work, here in your gallery exhibit, correct?

PF: Correct.

© Sebastiao Salgado / Amazonas Images[/caption]

AF: Right, right... But it’s interesting because he’s very connected to reality, what’s going on with our planet, that he has chosen, in a way, to show his incredible respect for this in black and white, which actually abstracts reality. It’s more of an abstraction of reality.

PF: It creates a power.

AF: Yes. But it’s interesting, from the artistic standpoint, in my mind, that he’s been very dedicated and pure about his vision by staying in black and white, especially now with all the new technology in digital.

PF: So, in a way he’s a throwback. I mean, he’s a classical black and white photographer in the tradition of Bresson or Strand, or Ansel Adams. Can you imagine Ansel Adams’ photographs all in color? His most celebrated, iconic images.

AF: Well, no, but Adams did actually explore color and shoot color, as did Weston, and even Bruce Davidson, who is a great street photographer.

PF: Yes, Subway series, absolutely.

AF: I mean, some of them do decide to go to color a little bit occasionally. Gordon Parks, I think, did a beautiful series of work in color.

PF: Yes. And Ernst Haas did his best work in color. I think everybody realizes what their instrument is as an artist, what’s their best instrument, their best...

AF: Is Salgado very good at editing his own work?

PF: [PAUSE] That’s a tough question.

AF: Well, a lot of people feel photographers are very bad at editing their own work. I mean, I’ve spoken to a number of curators in museums, and people like yourself, that have worked around photographers and sold photography for a long, long time. Many of them feel that photographers are not necessarily always their best own editors.

PF: I would go along with that.

Q:You would?