Fredric Roberts is an extraordinary man who abandoned a lucrative career on Wall Street to pursue his dream of becoming a photographer and traveling the world. He instantly  distinguished himself with a powerful vision. Today, his photographs are exhibited in numerous galleries, have won prestigious awards, and are published in three books.

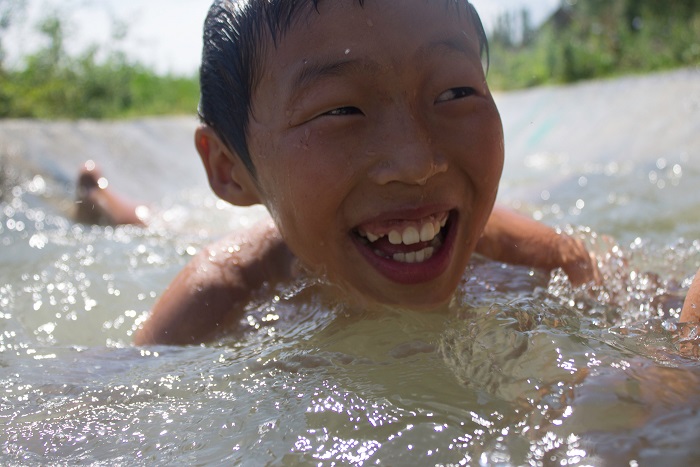

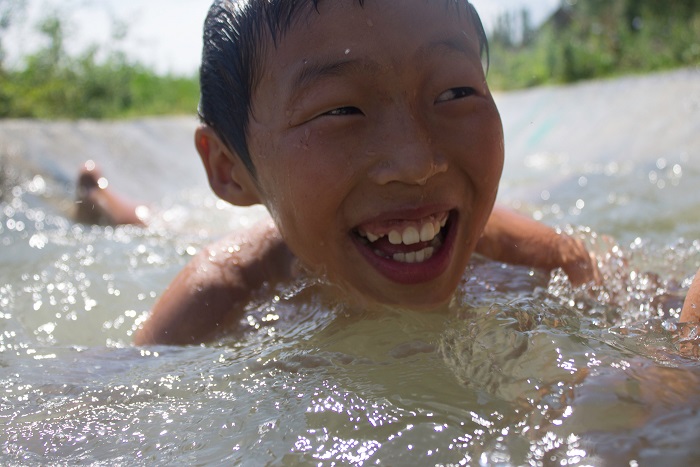

Currently, his remarkable journey has transformed into creating workshops to teach photography to high school students in various countries like India, Bhutan, Kyrgyzstan and more are planned. With a team of instructors, Canon digital cameras, laptop computers and Lightroom software, these workshops provide an incredible experience in learning the fundamentals of photography. His goal is to teach these kids to express themselves visually and to set them on a path to becoming committed, professional photographers who will help make the planet a healthier, more benevolent place to live.

In my interview with Roberts, he discussed in detail his amazing transformation from Wall Street to his exceptional work as a photographer and, finally, to the current incarnation leading workshops for teenagers in other countries.

Q: So right away, I was thinking, what inspired you to become a photographer?

A: Starting right out of Yale I went to Wall Street, and was trained by Lehman Brothers when Lehman Brothers was fabulous and classy. Then they moved me to Los Angeles in 1971, New Year’s Day. In 1976, I incubated my own firm, and in 1980 I went out on my own. I was doing mergers and private financing—a business, which in those days, people did not go out on their own to do. By ’86, I had had a moderate amount of success, but I was not happy. The ’80s changed the business substantially, and I wasn’t thrilled about it.

distinguished himself with a powerful vision. Today, his photographs are exhibited in numerous galleries, have won prestigious awards, and are published in three books.

Currently, his remarkable journey has transformed into creating workshops to teach photography to high school students in various countries like India, Bhutan, Kyrgyzstan and more are planned. With a team of instructors, Canon digital cameras, laptop computers and Lightroom software, these workshops provide an incredible experience in learning the fundamentals of photography. His goal is to teach these kids to express themselves visually and to set them on a path to becoming committed, professional photographers who will help make the planet a healthier, more benevolent place to live.

In my interview with Roberts, he discussed in detail his amazing transformation from Wall Street to his exceptional work as a photographer and, finally, to the current incarnation leading workshops for teenagers in other countries.

Q: So right away, I was thinking, what inspired you to become a photographer?

A: Starting right out of Yale I went to Wall Street, and was trained by Lehman Brothers when Lehman Brothers was fabulous and classy. Then they moved me to Los Angeles in 1971, New Year’s Day. In 1976, I incubated my own firm, and in 1980 I went out on my own. I was doing mergers and private financing—a business, which in those days, people did not go out on their own to do. By ’86, I had had a moderate amount of success, but I was not happy. The ’80s changed the business substantially, and I wasn’t thrilled about it.

I had a friend who worked in the travel business who said, “Gee, we just got permits for Tibet; the first people who are going to be able to see Tibet. Would you like to go? I can get you a permit and get you in.” I said, “Fabulous,” because I wanted to get away to think over my life. So I went away for six weeks. I went to Thailand, China, and Tibet. A couple of weeks before I left, somebody said, “Do you own a camera?” And I said, “No, I don’t.” They said, “Well, you’d better go buy one.” So I went into Samy’s relatives, at Bel-Air. I walked in and I must have had a huge bull’s-eye on me that said “Schmuck With A Credit Card.” And so they sold me this expensive Canon 35mm camera with the lenses and a million rolls of slide film. And I didn’t know anything. I’m on the plane flying to Bangkok with all this stuff laid out on a tray in front of me with a book trying to figure out where to put the battery.

And so, for six weeks I just went out on my own and shot pictures. When I came back, I didn’t know what to do with them. There was a course at UCLA taught by two National Geographic photographers; a husband and wife.

I had a friend who worked in the travel business who said, “Gee, we just got permits for Tibet; the first people who are going to be able to see Tibet. Would you like to go? I can get you a permit and get you in.” I said, “Fabulous,” because I wanted to get away to think over my life. So I went away for six weeks. I went to Thailand, China, and Tibet. A couple of weeks before I left, somebody said, “Do you own a camera?” And I said, “No, I don’t.” They said, “Well, you’d better go buy one.” So I went into Samy’s relatives, at Bel-Air. I walked in and I must have had a huge bull’s-eye on me that said “Schmuck With A Credit Card.” And so they sold me this expensive Canon 35mm camera with the lenses and a million rolls of slide film. And I didn’t know anything. I’m on the plane flying to Bangkok with all this stuff laid out on a tray in front of me with a book trying to figure out where to put the battery.

And so, for six weeks I just went out on my own and shot pictures. When I came back, I didn’t know what to do with them. There was a course at UCLA taught by two National Geographic photographers; a husband and wife.

I went there, and I brought my slides. They looked at the work, and the husband said to me, “Where did you learn how to photograph?” And I said, “Nowhere. I didn’t know anything. I didn’t even know where to put the battery.” And he said, “Well, we think you’re really good, and we’d like to teach you.”

So I went to their house for the first session, and I was there for four hours. And they were going crazy for all the pictures that I’d taken. I was supposed to come back the second week, but between Week 1 and Week 2, a couple things happened.

I went there, and I brought my slides. They looked at the work, and the husband said to me, “Where did you learn how to photograph?” And I said, “Nowhere. I didn’t know anything. I didn’t even know where to put the battery.” And he said, “Well, we think you’re really good, and we’d like to teach you.”

So I went to their house for the first session, and I was there for four hours. And they were going crazy for all the pictures that I’d taken. I was supposed to come back the second week, but between Week 1 and Week 2, a couple things happened.

First, I had decided on this trip that, even though I didn’t have a lot of money, I was going to retire; that I had enough money and if I lived modestly, I could retire. I’d always done a lot of charity work, and I figured I could spend the rest of my life doing charity work.

But the second thing that happened during that week was that I discovered that somebody had stolen all of my money – which is a story that is much too long to tell.

First, I had decided on this trip that, even though I didn’t have a lot of money, I was going to retire; that I had enough money and if I lived modestly, I could retire. I’d always done a lot of charity work, and I figured I could spend the rest of my life doing charity work.

But the second thing that happened during that week was that I discovered that somebody had stolen all of my money – which is a story that is much too long to tell.

So I went back to these people’s house and I gathered up all my slides. And I said to them, “Frankly I’m no longer thinking about retiring and taking up photography. I’m thinking about committing suicide.” And I took the camera and the lenses and the slides and threw them in a bag and threw them in a closet and did not look at them for 14 years.

Q: So what year is that now, when you put these things away?

A: 1986.

Q: 1986?

A: A lot of things happened between 1986 and 2000, many of which were positive, including the fact that people were so impressed with how I dealt with the fraud, that had not only ensnared me but a lot of other people, that I was elected chairman of the whole industry. I was elected Chairman of Wall Street, and I had a lot of notoriety and so forth. And I continued to do my charity work. Starting in ’89, I built at the Los Angeles Music Center what is I think, the most successful scholarship program in the country for high school students gifted in the arts - called the Music Center Spotlight Awards.

Later in the late ’90s I worked on a small committee that raised a large percentage of the money to build the Walt Disney Concert Hall. So I’ve always done a lot of charity work.

Then came 2000, and I felt as though I was financially secure enough to retire again. Only this time I really did it. And somebody said to me, “Didn’t you do photography once a long time ago?” And I said, “Oh, yeah. I forgot about that.” So I went back to look for this fellow, and he had died of prostate cancer. So I said, “I guess that’s the end of my photography.”

Q: This was the professor at UCLA?

A: Yes.

Q: The National Geographic guy?

A: Yes. And I said, “Well, I guess that’s the end of that.” And they said, “No, there are these workshops in Santa Fe. You should go.” So I called the workshops in Santa Fe, and they said, “We have a beginners’ course that starts with, “Where do you put the battery in the camera.” And it starts in about two weeks, and I think somebody just dropped out. We have one place available. Do you want to go?” And I said, “Sure.” I had nothing to do. I was retired.

So I went back to these people’s house and I gathered up all my slides. And I said to them, “Frankly I’m no longer thinking about retiring and taking up photography. I’m thinking about committing suicide.” And I took the camera and the lenses and the slides and threw them in a bag and threw them in a closet and did not look at them for 14 years.

Q: So what year is that now, when you put these things away?

A: 1986.

Q: 1986?

A: A lot of things happened between 1986 and 2000, many of which were positive, including the fact that people were so impressed with how I dealt with the fraud, that had not only ensnared me but a lot of other people, that I was elected chairman of the whole industry. I was elected Chairman of Wall Street, and I had a lot of notoriety and so forth. And I continued to do my charity work. Starting in ’89, I built at the Los Angeles Music Center what is I think, the most successful scholarship program in the country for high school students gifted in the arts - called the Music Center Spotlight Awards.

Later in the late ’90s I worked on a small committee that raised a large percentage of the money to build the Walt Disney Concert Hall. So I’ve always done a lot of charity work.

Then came 2000, and I felt as though I was financially secure enough to retire again. Only this time I really did it. And somebody said to me, “Didn’t you do photography once a long time ago?” And I said, “Oh, yeah. I forgot about that.” So I went back to look for this fellow, and he had died of prostate cancer. So I said, “I guess that’s the end of my photography.”

Q: This was the professor at UCLA?

A: Yes.

Q: The National Geographic guy?

A: Yes. And I said, “Well, I guess that’s the end of that.” And they said, “No, there are these workshops in Santa Fe. You should go.” So I called the workshops in Santa Fe, and they said, “We have a beginners’ course that starts with, “Where do you put the battery in the camera.” And it starts in about two weeks, and I think somebody just dropped out. We have one place available. Do you want to go?” And I said, “Sure.” I had nothing to do. I was retired. So I went to Santa Fe, and I went to my first class. It’s a one-week workshop, and I brought my slides. And they looked at my slides, and they said, “Where did you study photography?” And I said, “Nowhere.” And they said, “Well, we think you’re a prodigy. Maybe you should keep doing this.” So the next thing I knew I took another workshop and another, and another. In total I took ten workshops. And now I’m on the Board of Advisers of the Santa Fe Workshops, which I think are fantastic and…

Q: Yes. I’ve heard good things about them.

A: And Reid Callanan has become a very close friend of mine.

Q: Let me… forgive me for interrupting. I’m just curious. When you first started photographing, were you working with a digital camera or a film camera?

A: I worked with slides.

Q: Oh. So your first experience out was with film?

A: Yes, with slides.

Q: With transparencies, right?

A: Yes, all the way through the first workshops in Santa Fe, which is I think extremely good training.

Q: Definitely.

A: Because slides are so unforgiving.

Q: Exactly.

A: So when I was shooting slides, everybody said, “Well, you don’t know about the zone system, and you were never in a darkroom.” Like I was disadvantaged.

So I went to Santa Fe, and I went to my first class. It’s a one-week workshop, and I brought my slides. And they looked at my slides, and they said, “Where did you study photography?” And I said, “Nowhere.” And they said, “Well, we think you’re a prodigy. Maybe you should keep doing this.” So the next thing I knew I took another workshop and another, and another. In total I took ten workshops. And now I’m on the Board of Advisers of the Santa Fe Workshops, which I think are fantastic and…

Q: Yes. I’ve heard good things about them.

A: And Reid Callanan has become a very close friend of mine.

Q: Let me… forgive me for interrupting. I’m just curious. When you first started photographing, were you working with a digital camera or a film camera?

A: I worked with slides.

Q: Oh. So your first experience out was with film?

A: Yes, with slides.

Q: With transparencies, right?

A: Yes, all the way through the first workshops in Santa Fe, which is I think extremely good training.

Q: Definitely.

A: Because slides are so unforgiving.

Q: Exactly.

A: So when I was shooting slides, everybody said, “Well, you don’t know about the zone system, and you were never in a darkroom.” Like I was disadvantaged.

Q: Right, right.

A: But now I feel the same way about guys who never shot slides because slides, I think, are a fabulous discipline.

Q: Absolutely.

A: It wasn’t until 2005 that I started shooting digital. So, I took these workshops, and the next thing I knew a friend in New York looked at my work and said, “Gee, you should have a gallery look at these.” And another friend of mine said, “Gee, a publisher should look at these.” And suddenly I had a gallery show and a book and then awards and then another book and then more gallery shows and then museum shows. And soon, my work was in several major collections.

Q: So, you had no experiences of photographing, growing up as a child or a teenager?

A: Essentially, zero. I owned a camera that I used once a year. I didn’t know anything. Santa Fe really taught me, from the ground up. Whatever I am, formally, I owe to them. Whatever I was informally, on my own I guess, I owe to me, which I did in ’86 before I ever heard of Santa Fe. The fact is that they really helped me crystallize whatever it was that I had in my head and whatever talent I had.

Q: What do you think it is, that defines photography as an art form, that separates it from the other arts?

A: I think it’s more difficult now because everybody with a cell phone can take a perfectly exposed photograph. So everybody thinks they’re a photographer. Also, cameras are so sophisticated and automatic that everybody can do it. But there is still an art to it. Everybody knows how to write. Everybody went to the first, second, and third grade, and they know how to write, in the mechanical sense of writing script or block letters. This is what I tell the kids in the workshops that I teach, “We’ll teach you, the same way your first grade teacher taught you, how to shape letters. First you learn how to shape letters, and then you learn how to put them together into short words. Then you write longer words; you write sentences, and then you learn spelling and punctuation and syntax.

Q: Right, right.

A: But now I feel the same way about guys who never shot slides because slides, I think, are a fabulous discipline.

Q: Absolutely.

A: It wasn’t until 2005 that I started shooting digital. So, I took these workshops, and the next thing I knew a friend in New York looked at my work and said, “Gee, you should have a gallery look at these.” And another friend of mine said, “Gee, a publisher should look at these.” And suddenly I had a gallery show and a book and then awards and then another book and then more gallery shows and then museum shows. And soon, my work was in several major collections.

Q: So, you had no experiences of photographing, growing up as a child or a teenager?

A: Essentially, zero. I owned a camera that I used once a year. I didn’t know anything. Santa Fe really taught me, from the ground up. Whatever I am, formally, I owe to them. Whatever I was informally, on my own I guess, I owe to me, which I did in ’86 before I ever heard of Santa Fe. The fact is that they really helped me crystallize whatever it was that I had in my head and whatever talent I had.

Q: What do you think it is, that defines photography as an art form, that separates it from the other arts?

A: I think it’s more difficult now because everybody with a cell phone can take a perfectly exposed photograph. So everybody thinks they’re a photographer. Also, cameras are so sophisticated and automatic that everybody can do it. But there is still an art to it. Everybody knows how to write. Everybody went to the first, second, and third grade, and they know how to write, in the mechanical sense of writing script or block letters. This is what I tell the kids in the workshops that I teach, “We’ll teach you, the same way your first grade teacher taught you, how to shape letters. First you learn how to shape letters, and then you learn how to put them together into short words. Then you write longer words; you write sentences, and then you learn spelling and punctuation and syntax.  So the farther you go in school, you learn more about the more artistic aspects of language. But the fact is, if you don’t have anything to say, it doesn’t matter that you know how to write. And today, just like with cameras, you can use a word processor. You don’t even have to know how to form letters and write with a pen. You can sit down at a word processor that’ll check your spelling and fix your punctuation. But if you have nothing to say, it’s irrelevant. And it’s the same thing with photography. If you have nothing to say, then anybody - just like anybody -can sit down at a word processor, anybody can pick up a camera and take a well-exposed picture.

So I think it’s all about the content. And, yes, will people look at a beautiful picture better than they will at a picture that’s badly exposed or badly composed? Yes, they want to look at a pretty picture. But the fact is a pretty picture in and of itself is not enough. It’s an aesthetic experience. And I think that photography is no different.

Q: Yes. Well clearly, there’s the technique involved. I guess what I was trying to say…

A: No, no, it’s not that… What I’m saying is it’s not so much about technique.

So the farther you go in school, you learn more about the more artistic aspects of language. But the fact is, if you don’t have anything to say, it doesn’t matter that you know how to write. And today, just like with cameras, you can use a word processor. You don’t even have to know how to form letters and write with a pen. You can sit down at a word processor that’ll check your spelling and fix your punctuation. But if you have nothing to say, it’s irrelevant. And it’s the same thing with photography. If you have nothing to say, then anybody - just like anybody -can sit down at a word processor, anybody can pick up a camera and take a well-exposed picture.

So I think it’s all about the content. And, yes, will people look at a beautiful picture better than they will at a picture that’s badly exposed or badly composed? Yes, they want to look at a pretty picture. But the fact is a pretty picture in and of itself is not enough. It’s an aesthetic experience. And I think that photography is no different.

Q: Yes. Well clearly, there’s the technique involved. I guess what I was trying to say…

A: No, no, it’s not that… What I’m saying is it’s not so much about technique.

Q: Right.

A: It’s like when you learn how to drive a car, you’re worried about steering and braking and parking and all that. But after you know how to drive a car and it becomes second nature, it’s about where you’re going. It’s not about driving the car anymore.

Q: Precisely.

A: Or riding a bike, same thing. Once you don’t fall off and break your leg, it’s about where you are going. Well, it’s the same thing with photography. It’s what you are doing with this language because we teach these kids… we teach photography as a language.

Q: Right.

A: It’s like when you learn how to drive a car, you’re worried about steering and braking and parking and all that. But after you know how to drive a car and it becomes second nature, it’s about where you’re going. It’s not about driving the car anymore.

Q: Precisely.

A: Or riding a bike, same thing. Once you don’t fall off and break your leg, it’s about where you are going. Well, it’s the same thing with photography. It’s what you are doing with this language because we teach these kids… we teach photography as a language.

Q: Let’s back up just a second, and maybe you can explain what the workshops are about, and how the idea came to you to do the workshops.

A: Okay. Well, here was this photography career that sprang out of me almost wholly formed, vastly refined by the Santa Fe workshops. And I was always a traveler. My business took me around the world, since a lot of what I did was international. I always liked traveling. Moreover, I was always surrounded by people who defined themselves by money. I mean, Wall Street in general is guys chasing after money all the time. And what I found (particularly in third world countries which is where I, out of sheer serendipity wound up) is that people had tremendously rich lives despite having no money. I met a lot of subsistence farmers who live in villages where they have incredible family lives and great relationships with their neighbors; community lives. They were very diligent, very honest and very hard working and wonderful to their kids. And their kids were wonderful to them. You had four generations living in one house, and everybody was taking care of each other. They didn’t have two nickels to rub together, but they were wonderful people and generous to a fault. You walk through a village in the middle of some third world country where people are really subsistence farmers, and the first thing they do is invite you in for some tea, or food, or lunch, or breakfast, or dinner. I live in Los Angeles. You could come to my street and you could walk up and down that street for ten years, and nobody would come out and say, “Hey, do you want to come in for coffee and a bagel?”

Q: Forgive me for laughing!

A: Right. But, I mean, they’d call the cops and say,

Q: Yes, yes…

A: “There’s some strange guy out here walking around, and I don’t know what he’s doing here.”

Q: Right.

A: That’s the difference. I didn’t know that I had a point of view with my photography. I didn’t realize it. Somebody at Santa Fe once said, “You don’t have to have a point of view. But if you have one, your photography will be better.” And after shooting for a few years, I looked at my stuff and I said, “You know, there is something that’s sort of subliminal. There is a subliminal message here and that is that money doesn’t make you rich.” My books took on this theme.

Q: Yes, I know that.

A: My three books start with an old religious text that says, “Who is rich? The person who’s happy with what he has.” You can look at my work and see that, or you can look at my work and not see that. But I hope that the message is in there; that there’s more to life than just making money.

Q: Let’s back up just a second, and maybe you can explain what the workshops are about, and how the idea came to you to do the workshops.

A: Okay. Well, here was this photography career that sprang out of me almost wholly formed, vastly refined by the Santa Fe workshops. And I was always a traveler. My business took me around the world, since a lot of what I did was international. I always liked traveling. Moreover, I was always surrounded by people who defined themselves by money. I mean, Wall Street in general is guys chasing after money all the time. And what I found (particularly in third world countries which is where I, out of sheer serendipity wound up) is that people had tremendously rich lives despite having no money. I met a lot of subsistence farmers who live in villages where they have incredible family lives and great relationships with their neighbors; community lives. They were very diligent, very honest and very hard working and wonderful to their kids. And their kids were wonderful to them. You had four generations living in one house, and everybody was taking care of each other. They didn’t have two nickels to rub together, but they were wonderful people and generous to a fault. You walk through a village in the middle of some third world country where people are really subsistence farmers, and the first thing they do is invite you in for some tea, or food, or lunch, or breakfast, or dinner. I live in Los Angeles. You could come to my street and you could walk up and down that street for ten years, and nobody would come out and say, “Hey, do you want to come in for coffee and a bagel?”

Q: Forgive me for laughing!

A: Right. But, I mean, they’d call the cops and say,

Q: Yes, yes…

A: “There’s some strange guy out here walking around, and I don’t know what he’s doing here.”

Q: Right.

A: That’s the difference. I didn’t know that I had a point of view with my photography. I didn’t realize it. Somebody at Santa Fe once said, “You don’t have to have a point of view. But if you have one, your photography will be better.” And after shooting for a few years, I looked at my stuff and I said, “You know, there is something that’s sort of subliminal. There is a subliminal message here and that is that money doesn’t make you rich.” My books took on this theme.

Q: Yes, I know that.

A: My three books start with an old religious text that says, “Who is rich? The person who’s happy with what he has.” You can look at my work and see that, or you can look at my work and not see that. But I hope that the message is in there; that there’s more to life than just making money.

So when I retired in 2000, I certainly was not as rich as all the other guys in my business. But I didn’t care. I had enough for me. There’s nothing in my life that I can’t afford to do that I want to do. So I feel totally satisfied about where I am. But what happened was that after awhile the photography, with all the success and all the awards and all the shows and all the good feedback and all the good feelings, eventually had sort of diminishing returns. It became like work again. Would people buy the work or not buy the work? Were people going to sell the work properly or not sell the work properly? Was I going to get paid in the end or not get paid in the end? What about my books? Would they be properly promoted? Who was going to sell them? And after awhile I just said to myself, “I don’t need this. Photography is not going to make me rich, and it’s not going to make me poor. The only reason to do it is because I really love doing it.”

Q: So it didn’t diminish your joy of actually shooting and going places, correct?

A: Not the photography itself. Interestingly, two years ago I went to the Kumbh Mela. I don’t know if you’re familiar with that. It is a once-every-12-years incredible Hindu festival where 40 million people come periodically over a two-month period; 40 million, okay? That’s not a typo, and that’s not an exaggeration. They come and they bathe in the Ganges, and they wash away their sins. I mean, 2 million people go to the Hajj in Mecca, and everybody gets excited about it. This is 20 times more people. I was there for six weeks living in a tent; albeit a tent with a toilet and a shower. It was a tent. And I was there and experiencing that. To experience it live with a camera in your hand to me is a more enriching experience than without a camera in my hand, although I don’t always photograph everything I see and love. I always think the best camera you have is your eyes, and the best recording device you have is your brain. But often, being able to photograph things and having the ability to use a camera and shoot pictures enhances the experience for me. So I loved being there, and I loved taking pictures of it. I haven’t figured out yet, as an example, what I’m going to do with that work. We’ll see.

So when I retired in 2000, I certainly was not as rich as all the other guys in my business. But I didn’t care. I had enough for me. There’s nothing in my life that I can’t afford to do that I want to do. So I feel totally satisfied about where I am. But what happened was that after awhile the photography, with all the success and all the awards and all the shows and all the good feedback and all the good feelings, eventually had sort of diminishing returns. It became like work again. Would people buy the work or not buy the work? Were people going to sell the work properly or not sell the work properly? Was I going to get paid in the end or not get paid in the end? What about my books? Would they be properly promoted? Who was going to sell them? And after awhile I just said to myself, “I don’t need this. Photography is not going to make me rich, and it’s not going to make me poor. The only reason to do it is because I really love doing it.”

Q: So it didn’t diminish your joy of actually shooting and going places, correct?

A: Not the photography itself. Interestingly, two years ago I went to the Kumbh Mela. I don’t know if you’re familiar with that. It is a once-every-12-years incredible Hindu festival where 40 million people come periodically over a two-month period; 40 million, okay? That’s not a typo, and that’s not an exaggeration. They come and they bathe in the Ganges, and they wash away their sins. I mean, 2 million people go to the Hajj in Mecca, and everybody gets excited about it. This is 20 times more people. I was there for six weeks living in a tent; albeit a tent with a toilet and a shower. It was a tent. And I was there and experiencing that. To experience it live with a camera in your hand to me is a more enriching experience than without a camera in my hand, although I don’t always photograph everything I see and love. I always think the best camera you have is your eyes, and the best recording device you have is your brain. But often, being able to photograph things and having the ability to use a camera and shoot pictures enhances the experience for me. So I loved being there, and I loved taking pictures of it. I haven’t figured out yet, as an example, what I’m going to do with that work. We’ll see.

Q: Yes, I understand, now getting back to the workshops,

A: To the workshops.

Q: … how the workshops happened?

A: So here I am with this career that superficially looks really good, but I’m starting to feel less and less good about it. About four years ago somebody came up to me and said, “Would you like to do a workshop? There’s an NGO in India, and they’re looking to do a workshop.” And I said, “Well, you know, it’s…”

Q: Forgive me. What is an NGO?

A: Non-Government Organization. It’s basically a charity.

Q: Right, excuse me.

A: Like the Red Cross.

Q: Yes, I understand, now getting back to the workshops,

A: To the workshops.

Q: … how the workshops happened?

A: So here I am with this career that superficially looks really good, but I’m starting to feel less and less good about it. About four years ago somebody came up to me and said, “Would you like to do a workshop? There’s an NGO in India, and they’re looking to do a workshop.” And I said, “Well, you know, it’s…”

Q: Forgive me. What is an NGO?

A: Non-Government Organization. It’s basically a charity.

Q: Right, excuse me.

A: Like the Red Cross.

Q: I just wanted to be clear about it.

A: Right. So I said, “Great. Great.” It was consistent with what I was doing at the Music Center. It was consistent with my life. So I went there, and I set it up. I raised some money, and I bought equipment. I bought 20 cameras, and I bought four MacBook Pros. I put together a faculty, and we flew over and we taught our first workshop to Indian kids. I always thought strategically, and I had sort of a plan that was beginning to percolate in my head that was becoming more refined as I did it. I wanted half boys and half girls because I wanted a gender mix. And in the third world countries, girls are generally…

Q: Right… Not treated the same?

A: …marginalized.

Q: …equal. That’s right.

Q: I just wanted to be clear about it.

A: Right. So I said, “Great. Great.” It was consistent with what I was doing at the Music Center. It was consistent with my life. So I went there, and I set it up. I raised some money, and I bought equipment. I bought 20 cameras, and I bought four MacBook Pros. I put together a faculty, and we flew over and we taught our first workshop to Indian kids. I always thought strategically, and I had sort of a plan that was beginning to percolate in my head that was becoming more refined as I did it. I wanted half boys and half girls because I wanted a gender mix. And in the third world countries, girls are generally…

Q: Right… Not treated the same?

A: …marginalized.

Q: …equal. That’s right.

A: Right, marginalized. And I wanted half city and half country kids because I wanted a cultural mix of kids who didn’t normally intermingle. It worked out extremely well. The work was wonderful but the NGO really did nothing with the work and so I was put off by that. I came back and did a second workshop the following year that included bringing the original kids back for a special three-day advanced workshop in which, additionally, we gave them very advanced Lightroom skills on the computers.

Q: I’m just curious about something; had these students ever taken pictures before?

A: No.

Q: Had they ever held cameras before?

A: No.

Q: Did they have any language at all, or skills in computers . . . Anything?

A: No.

Q: …for you to build on? Nothing?

A: No.

Q: Really?

A: Yes. And that’s a huge advantage.

Q: It’s a huge advantage? Can you explain that?

A: Huge advantage because… But I’ll get to that.

A: Right, marginalized. And I wanted half city and half country kids because I wanted a cultural mix of kids who didn’t normally intermingle. It worked out extremely well. The work was wonderful but the NGO really did nothing with the work and so I was put off by that. I came back and did a second workshop the following year that included bringing the original kids back for a special three-day advanced workshop in which, additionally, we gave them very advanced Lightroom skills on the computers.

Q: I’m just curious about something; had these students ever taken pictures before?

A: No.

Q: Had they ever held cameras before?

A: No.

Q: Did they have any language at all, or skills in computers . . . Anything?

A: No.

Q: …for you to build on? Nothing?

A: No.

Q: Really?

A: Yes. And that’s a huge advantage.

Q: It’s a huge advantage? Can you explain that?

A: Huge advantage because… But I’ll get to that.

Q: Right.

A: So we came back the second year, and we did an advanced workshop with those first 20 kids, and then we did a new beginners workshop with 20 new kids. Sadly, I realized that the NGO was not really using the students’ work, and I was very turned off. So I tried to move the workshop to another venue but it was too complicated. So I just said to myself, “You know what? This was a nice exercise. It turned out in one respect very well; in another respect not so well. I’m just going to stop. That’s the end of it.” I checked the box, and it was over.

Miraculously a year later, a very large charitable institution called me and said, “We heard about your workshops. We want you to do this. We’re a big operation. We’re several hundred million dollars in volume and…”

Q: Was this an American charity?

A: This was an American charity—worldwide charity, but it was the American member of the board. So I said, “Okay, fine. I like the idea. If I’m with somebody who’s substantial, that makes life easier for me.” So I raised some more money and was going to do it, and then I found out that they take a large portion of money out of the budget for their own overhead charges. In fact,

Q: Right.

A: So we came back the second year, and we did an advanced workshop with those first 20 kids, and then we did a new beginners workshop with 20 new kids. Sadly, I realized that the NGO was not really using the students’ work, and I was very turned off. So I tried to move the workshop to another venue but it was too complicated. So I just said to myself, “You know what? This was a nice exercise. It turned out in one respect very well; in another respect not so well. I’m just going to stop. That’s the end of it.” I checked the box, and it was over.

Miraculously a year later, a very large charitable institution called me and said, “We heard about your workshops. We want you to do this. We’re a big operation. We’re several hundred million dollars in volume and…”

Q: Was this an American charity?

A: This was an American charity—worldwide charity, but it was the American member of the board. So I said, “Okay, fine. I like the idea. If I’m with somebody who’s substantial, that makes life easier for me.” So I raised some more money and was going to do it, and then I found out that they take a large portion of money out of the budget for their own overhead charges. In fact,

Q: Just to be clear, did they want you to come to the table with money you had already raised on your own?

A: Yes.

Q: So they wanted to participate in money and funds you had already…?

A: Raised, and they were going to take money off the top. And then they billed us for all kinds of additional expenses. In order to mitigate this, I set up my own 501(c)(3). I took the money into my own foundation. I added some of my own money. I added some of other people’s money. I was committed to two workshops with them, which I completed.

Q: Right.

A: But now I’ve found great partners; wonderful partners really. And I’m thrilled. So now we have incredible opportunities. We have NGO partners around the world. We have more than we can handle. We have more opportunities to do workshops than we have capacity for.

Q: Just to be clear, did they want you to come to the table with money you had already raised on your own?

A: Yes.

Q: So they wanted to participate in money and funds you had already…?

A: Raised, and they were going to take money off the top. And then they billed us for all kinds of additional expenses. In order to mitigate this, I set up my own 501(c)(3). I took the money into my own foundation. I added some of my own money. I added some of other people’s money. I was committed to two workshops with them, which I completed.

Q: Right.

A: But now I’ve found great partners; wonderful partners really. And I’m thrilled. So now we have incredible opportunities. We have NGO partners around the world. We have more than we can handle. We have more opportunities to do workshops than we have capacity for.

Q: Great!

A: We have plenty of financial capacity. And thanks to Samy’s we have plenty of equipment.

Q: Fantastic!

A: We have plenty of kids. The work that the kids produce is extraordinary. Everybody who sees the kids’ work says, “This is unbelievable; literally unbelievable.” And it doesn’t matter whether it’s the local NGOs, the press . . . Anyone in the U.S. who looks at the slide shows says, “This is impossible. This could not have been done by third world high school students who never touched a camera before.”

Q: I’m just curious about something; had these students ever taken pictures before?

A: No.

Q: Great!

A: We have plenty of financial capacity. And thanks to Samy’s we have plenty of equipment.

Q: Fantastic!

A: We have plenty of kids. The work that the kids produce is extraordinary. Everybody who sees the kids’ work says, “This is unbelievable; literally unbelievable.” And it doesn’t matter whether it’s the local NGOs, the press . . . Anyone in the U.S. who looks at the slide shows says, “This is impossible. This could not have been done by third world high school students who never touched a camera before.”

Q: I’m just curious about something; had these students ever taken pictures before?

A: No.

Q: Had they ever held cameras before?

A: No.

Q: Did they have any language at all, or skills in computers . . . Anything?

A: No.

Q: …for you to build on? Nothing?

A: No.

Q: Really?

A: Yes. And that’s a huge advantage.

Q: It’s a huge advantage? Can you explain that?

A: Huge advantage because… But I’ll get to that.

Q: Right.

A: So we came back the second year, and we did an advanced workshop with those first 20 kids, and then we did a new beginners workshop with 20 new kids. Sadly, I realized that the NGO was not really using the students’ work, and I was very turned off. So I tried to move the workshop to another venue but it was too complicated. So I just said to myself, “You know what? This was a nice exercise. It turned out in one respect very well; in another respect not so well. I’m just going to stop. That’s the end of it.” I checked the box, and it was over.

Miraculously a year later, a very large charitable institution called me and said, “We heard about your workshops. We want you to do this. We’re a big operation. We’re several hundred million dollars in volume and…”

Q: Had they ever held cameras before?

A: No.

Q: Did they have any language at all, or skills in computers . . . Anything?

A: No.

Q: …for you to build on? Nothing?

A: No.

Q: Really?

A: Yes. And that’s a huge advantage.

Q: It’s a huge advantage? Can you explain that?

A: Huge advantage because… But I’ll get to that.

Q: Right.

A: So we came back the second year, and we did an advanced workshop with those first 20 kids, and then we did a new beginners workshop with 20 new kids. Sadly, I realized that the NGO was not really using the students’ work, and I was very turned off. So I tried to move the workshop to another venue but it was too complicated. So I just said to myself, “You know what? This was a nice exercise. It turned out in one respect very well; in another respect not so well. I’m just going to stop. That’s the end of it.” I checked the box, and it was over.

Miraculously a year later, a very large charitable institution called me and said, “We heard about your workshops. We want you to do this. We’re a big operation. We’re several hundred million dollars in volume and…”

Q: That was a question I had. Why did you choose high school age?

A: Well, this is what I learned with my scholarship program at the Music Center. High school kids are at a very pivotal point in their life. It’s great. When I was in grade school and I was in the third, fourth grade…

They take you to see a ballet or something, and you have this vague notion of what a ballet is. But if you’re 14-years-old and you go to a ballet and it impresses you, you’re going to really think about it. It could be a life-changer. We literally changed the lives of the kids who were in the scholarship program at the Music Center. So it’s a very formative time of their lives, and it’s a moment at which, if you can impress them with a concept or give them a skill that they can use, they will really leverage it at that point.

Q: That’s a very good answer. What kind of equipment do the kids get to work with?

A: We use Canon Rebels with an 18–55 lens, which is an unfortunate lens, but it’s what they come with. It’s what we could afford in the beginning when l bought them. Now, thanks to Samy, we have a great relationship with Canon.

Q: Samy is enthusiastically committed to what you’re doing and helping you with your workshops.

A: We teach with 20 cameras, and we leave four cameras behind. The goal is not to have kids have a fabulous one-week experience and then leave and have the air go out of the balloon. We want these kids to have a skill that they will use throughout their life.

Q: That was a question I had. Why did you choose high school age?

A: Well, this is what I learned with my scholarship program at the Music Center. High school kids are at a very pivotal point in their life. It’s great. When I was in grade school and I was in the third, fourth grade…

They take you to see a ballet or something, and you have this vague notion of what a ballet is. But if you’re 14-years-old and you go to a ballet and it impresses you, you’re going to really think about it. It could be a life-changer. We literally changed the lives of the kids who were in the scholarship program at the Music Center. So it’s a very formative time of their lives, and it’s a moment at which, if you can impress them with a concept or give them a skill that they can use, they will really leverage it at that point.

Q: That’s a very good answer. What kind of equipment do the kids get to work with?

A: We use Canon Rebels with an 18–55 lens, which is an unfortunate lens, but it’s what they come with. It’s what we could afford in the beginning when l bought them. Now, thanks to Samy, we have a great relationship with Canon.

Q: Samy is enthusiastically committed to what you’re doing and helping you with your workshops.

A: We teach with 20 cameras, and we leave four cameras behind. The goal is not to have kids have a fabulous one-week experience and then leave and have the air go out of the balloon. We want these kids to have a skill that they will use throughout their life.

Q: Maybe even become professional photographers?

A: We are thrilled if they become professionals, and occasionally they do. But even more important than that (although that in a third world country is enormously important) is that they have the ability to literally change their world, because they can use these cameras in very powerful ways. They can tell stories. They can tell the story of the NGO after we leave. They can tell the story of healthcare or education or nutrition or micro-finance or electrical power in rural areas. They can tell any story.

We don’t go where there’s strife, and we don’t shoot stories of that strife. We don’t shoot stories that are political in nature. We shoot humanitarian stories or global stories.

Q: So the kids get an assignment in a sense?

A: They get three assignments during the week, and if you want I can go through the template of the workshop.

Q: Maybe even become professional photographers?

A: We are thrilled if they become professionals, and occasionally they do. But even more important than that (although that in a third world country is enormously important) is that they have the ability to literally change their world, because they can use these cameras in very powerful ways. They can tell stories. They can tell the story of the NGO after we leave. They can tell the story of healthcare or education or nutrition or micro-finance or electrical power in rural areas. They can tell any story.

We don’t go where there’s strife, and we don’t shoot stories of that strife. We don’t shoot stories that are political in nature. We shoot humanitarian stories or global stories.

Q: So the kids get an assignment in a sense?

A: They get three assignments during the week, and if you want I can go through the template of the workshop.

Q: Yes, please.

A: The workshop is a one-week workshop. It generally starts - and I say “generally” because everything is flexible in life, as you know, especially in photography - we start on Sunday; we end on Saturday. We say it’s a one-week workshop, but actually there’s only five days of instruction. So we give them these cameras on Day 1, Sunday morning, and they can only shoot on manual mode, period.

Q: Yes, please.

A: The workshop is a one-week workshop. It generally starts - and I say “generally” because everything is flexible in life, as you know, especially in photography - we start on Sunday; we end on Saturday. We say it’s a one-week workshop, but actually there’s only five days of instruction. So we give them these cameras on Day 1, Sunday morning, and they can only shoot on manual mode, period.

Q: Quickly, how do you deal with the language issues, concerning the instruction?

A: We have translators, and sometimes it’s complex because we have kids who speak the national language. Then sometimes the country kids speak a tribal language or a local language. So in India we had people speaking Hindi and people speaking Garasia. In Tajikistan we had people speaking Russian and people speaking Tajik. In Kyrgyzstan we had people speaking Russian; we had people speaking Kyrgyz. So you had two simultaneous translators going on while your lecturing, and it’s hard to tell a joke.

Q: Quickly, how do you deal with the language issues, concerning the instruction?

A: We have translators, and sometimes it’s complex because we have kids who speak the national language. Then sometimes the country kids speak a tribal language or a local language. So in India we had people speaking Hindi and people speaking Garasia. In Tajikistan we had people speaking Russian and people speaking Tajik. In Kyrgyzstan we had people speaking Russian; we had people speaking Kyrgyz. So you had two simultaneous translators going on while your lecturing, and it’s hard to tell a joke.

Q: (LAUGHTER)

A: You know what I mean? By the time the punch line comes out, nobody knows what you said, and you forget what you said. So it’s hard. Anyway, Sunday and Monday we teach them the basics of photography, and you’d be astounded at how fast these kids pick up manual photography.

Q: Like the concept of an exposure, and what it means?

A: Absolutely. Such as the relationship between shutter speed and blurring and freezing action, and the concept of aperture and depth of field. Interestingly, at the end of the week we accumulate some of their best pictures for a special slide show of their best of the week, and several of those pictures come from the first day because they’re completely unfiltered.

Q: (LAUGHTER)

A: You know what I mean? By the time the punch line comes out, nobody knows what you said, and you forget what you said. So it’s hard. Anyway, Sunday and Monday we teach them the basics of photography, and you’d be astounded at how fast these kids pick up manual photography.

Q: Like the concept of an exposure, and what it means?

A: Absolutely. Such as the relationship between shutter speed and blurring and freezing action, and the concept of aperture and depth of field. Interestingly, at the end of the week we accumulate some of their best pictures for a special slide show of their best of the week, and several of those pictures come from the first day because they’re completely unfiltered.

Q: interesting.

A: These kids have a person inside them who is their creative genie. If they have something to say, it’s going to come out. We teach them how to express themselves visually, and it comes out. So Sunday and Monday is all about the camera and exercises and exposure. And they get it very quickly.

Q: So that represents a full day’s class?

A: Full day. We start at 8:00 in the morning usually and sometimes we’d go to 8:00, 9:00, 10:00 at night. It’s a long day. And it’s a longer day if you’re my age or the age of the rest of the faculty because we’re 12 hours off on the jetlag, we’ve been flying for 24 hours to get there. We have a couple days to prepare, and now suddenly we’re up at a breakfast at 6:00 a.m. organizing our day that goes on until 10:00 p.m. Then people get on their computers and try and call home and do things and then go to sleep. It’s exhausting. It’s exhausting for the kids, and it’s exhausting for the faculty. But it’s an exhilarating exhaustion.

Q: I can imagine!

A: It’s so stimulating. There’s no way really to describe it. So then comes Tuesday, and Tuesday is the first of three stories. The stories are determined before we leave for the workshop. The NGO gives us the three stories, which we analyze very carefully before we go. The stories have to be compelling visually, because there are no words. There are no captions. There’s no text. This isn’t like some video where somebody shoots a picture of a leaf and then talks for an hour about agriculture. If it isn’t visual, if you can’t say it visually, you’re not saying it. If you look at the slide shows that the kids have done and you look at things like everything from sending them to preschools where it’s fun to look at kids playing on jungle gyms and digging in sandpits, to having them go into emergency rooms where people were literally dying in front of them. Some of these stories are very powerful, and some of them are very meaningful - like delivering electrical power, hydroelectric power to the rural areas of Tajikistan. That’s a critical piece of infrastructure that the NGO is providing for the country. So these kids are telling really powerful stories.

Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday they get a half a day of classroom work, and then we send them out to tell stories, to shoot stories. When I said we only give them five days of instruction, now we’re at Thursday. That’s the end of the fifth day.

On Friday we send them out on a free shoot. We give them something that the NGO wants, that’s not necessarily story-related, such as “We have a school here; would you take pretty pictures of the school?” So we do that. We send them out on that, and the faculty then spends Friday editing the slide show all day and all night. And we create slide shows that are best of work of the kids from each group. What I neglected to tell you is that on Day 1 we divide the kids into four groups of five, and we’re very careful to try and divide them up between boys and girls and city and country.

Q: Do you notice a difference between the students from the country and the ones from the city?

A: Absolutely.

Q: In how they view things and how they express themselves?

A: But the fact is that the mix works very well. The kids from the city think they’re very sophisticated and the kids from the country start out feeling sort of socially insecure. As soon as the city kid finds out that the kid from the country has an incredible eye and has taken some fabulous pictures, suddenly the roles are reversed.

Q: He’s got a new respect for the…?

A: He’s got a new respect for him. They work together, and then help each other out. Then suddenly they’re friends, and it’s a very powerful formula. And so we’re sticking with this formula.

Q: How are the kids selected?

A: The NGO selects them based on the template that we give them. The first piece of the template is boys and girls, city and country. Then we want as little previous photographic experience as possible, but some interest in the subject matter. So if we’re going to shoot the Aga Khan stories or the Bhutan Foundation stories or the Asia Foundation stories or whatever, we want the kids to be interested in the subject matter. Whether it’s the environment or healthcare, nutrition, livestock, farming procedures, microfinance, rural electrification - whatever it is, we want the kids to be interested in it. And they vet those kids based on that. Maybe they have them do an essay, or they have them come in and be interviewed. But we’re only talking about 20 kids, so it’s not hard.

Q: interesting.

A: These kids have a person inside them who is their creative genie. If they have something to say, it’s going to come out. We teach them how to express themselves visually, and it comes out. So Sunday and Monday is all about the camera and exercises and exposure. And they get it very quickly.

Q: So that represents a full day’s class?

A: Full day. We start at 8:00 in the morning usually and sometimes we’d go to 8:00, 9:00, 10:00 at night. It’s a long day. And it’s a longer day if you’re my age or the age of the rest of the faculty because we’re 12 hours off on the jetlag, we’ve been flying for 24 hours to get there. We have a couple days to prepare, and now suddenly we’re up at a breakfast at 6:00 a.m. organizing our day that goes on until 10:00 p.m. Then people get on their computers and try and call home and do things and then go to sleep. It’s exhausting. It’s exhausting for the kids, and it’s exhausting for the faculty. But it’s an exhilarating exhaustion.

Q: I can imagine!

A: It’s so stimulating. There’s no way really to describe it. So then comes Tuesday, and Tuesday is the first of three stories. The stories are determined before we leave for the workshop. The NGO gives us the three stories, which we analyze very carefully before we go. The stories have to be compelling visually, because there are no words. There are no captions. There’s no text. This isn’t like some video where somebody shoots a picture of a leaf and then talks for an hour about agriculture. If it isn’t visual, if you can’t say it visually, you’re not saying it. If you look at the slide shows that the kids have done and you look at things like everything from sending them to preschools where it’s fun to look at kids playing on jungle gyms and digging in sandpits, to having them go into emergency rooms where people were literally dying in front of them. Some of these stories are very powerful, and some of them are very meaningful - like delivering electrical power, hydroelectric power to the rural areas of Tajikistan. That’s a critical piece of infrastructure that the NGO is providing for the country. So these kids are telling really powerful stories.

Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday they get a half a day of classroom work, and then we send them out to tell stories, to shoot stories. When I said we only give them five days of instruction, now we’re at Thursday. That’s the end of the fifth day.

On Friday we send them out on a free shoot. We give them something that the NGO wants, that’s not necessarily story-related, such as “We have a school here; would you take pretty pictures of the school?” So we do that. We send them out on that, and the faculty then spends Friday editing the slide show all day and all night. And we create slide shows that are best of work of the kids from each group. What I neglected to tell you is that on Day 1 we divide the kids into four groups of five, and we’re very careful to try and divide them up between boys and girls and city and country.

Q: Do you notice a difference between the students from the country and the ones from the city?

A: Absolutely.

Q: In how they view things and how they express themselves?

A: But the fact is that the mix works very well. The kids from the city think they’re very sophisticated and the kids from the country start out feeling sort of socially insecure. As soon as the city kid finds out that the kid from the country has an incredible eye and has taken some fabulous pictures, suddenly the roles are reversed.

Q: He’s got a new respect for the…?

A: He’s got a new respect for him. They work together, and then help each other out. Then suddenly they’re friends, and it’s a very powerful formula. And so we’re sticking with this formula.

Q: How are the kids selected?

A: The NGO selects them based on the template that we give them. The first piece of the template is boys and girls, city and country. Then we want as little previous photographic experience as possible, but some interest in the subject matter. So if we’re going to shoot the Aga Khan stories or the Bhutan Foundation stories or the Asia Foundation stories or whatever, we want the kids to be interested in the subject matter. Whether it’s the environment or healthcare, nutrition, livestock, farming procedures, microfinance, rural electrification - whatever it is, we want the kids to be interested in it. And they vet those kids based on that. Maybe they have them do an essay, or they have them come in and be interviewed. But we’re only talking about 20 kids, so it’s not hard.

Q: I see.

A: So, Friday we’re editing. They’re out doing their free shoot. They come back Friday afternoon; they download. For graduation, we have each kid pick their absolute favorite image of the week, and we make prints. We go to a local print shop and work on their color balance and so forth, and we make sure that they’re really good. Today you can go almost anywhere and find a good photo print shop. Then we make prints; two copies of each of the kids’ favorite print. On Friday afternoon we bring them back, and we have them sign the prints and it is a very emotional experience.

Q: So, are these 8x10s, basically?

A: Oh, bigger.

Q: Bigger?

A: Bigger, yes. They’re like 16 x 20s.

Q: Okay. So you give the kids hard copy prints of what they…

A: Hard copy prints. But when they come in to sign those prints and they see their prints for the first time, they’re crying. We’re crying.

Q: Wow!

A: The staff is crying. Everybody’s crying. There’s a lot of crying. There may be no crying in baseball, but there’s a lot of crying in these workshops.

Q: Do these kids go home at night and then come back? Or do you put them up for the duration of the workshop?

A: Rarely they do go home, but generally we don’t like them to, so we put them up. Usually we put them up in a hostel or we put them up in a school dormitory. But we take really good care of them. And the cultures that we’re dealing with are such that girls of that age do not sleep in the same building with boys. So we go through a huge process of…

Q: I see.

A: So, Friday we’re editing. They’re out doing their free shoot. They come back Friday afternoon; they download. For graduation, we have each kid pick their absolute favorite image of the week, and we make prints. We go to a local print shop and work on their color balance and so forth, and we make sure that they’re really good. Today you can go almost anywhere and find a good photo print shop. Then we make prints; two copies of each of the kids’ favorite print. On Friday afternoon we bring them back, and we have them sign the prints and it is a very emotional experience.

Q: So, are these 8x10s, basically?

A: Oh, bigger.

Q: Bigger?

A: Bigger, yes. They’re like 16 x 20s.

Q: Okay. So you give the kids hard copy prints of what they…

A: Hard copy prints. But when they come in to sign those prints and they see their prints for the first time, they’re crying. We’re crying.

Q: Wow!

A: The staff is crying. Everybody’s crying. There’s a lot of crying. There may be no crying in baseball, but there’s a lot of crying in these workshops.

Q: Do these kids go home at night and then come back? Or do you put them up for the duration of the workshop?

A: Rarely they do go home, but generally we don’t like them to, so we put them up. Usually we put them up in a hostel or we put them up in a school dormitory. But we take really good care of them. And the cultures that we’re dealing with are such that girls of that age do not sleep in the same building with boys. So we go through a huge process of…

Q: Separation…

A: …convincing the mothers that it’s okay to let their daughters come with us. Then we have to show them the security measures and the chaperoning systems and so forth. I’m used to it. In fact, I know more than the NGOs do. They’re amazed. The local people are amazed that I understand their culture better than they do so that I can show them how to thread the needle.

Q: What has been the biggest surprise for you personally about this experience? I mean, did anything come about that you absolutely didn’t expect?

A: How good the kids are.

Q: Really?

A: How good the kids are. The kids are so good that…

Q: As photographers?

A: As photographers, as storytellers, as creative people . . . not just artists, but expressive artists.

Q: Do you show them celebrated and historical photo essays in class, done by other famous photographers, like Eugene Smith?

A: We show them our own work.

Q: Really? Your own work?

A: And to a certain extent they mimic our work a little bit. But the fact is that our work and the work that they’re asked to do is really different. For instance, I have a book on India. I have a book on Burma. I have a book on South Asia.

Q: I was looking at those.

A: Right.

Q: The looked great on the Internet!

A: Thank you. I’m reasonably accomplished, and I’m the only American ever to have won the Best Foreign Photographer for India award.

Q: And you do all your own editing yourself? Do you work with an editor?

A: I have people who help me—I mean, curators who will help me curate my books.

Q: Sure.

A: The fact is that I’m not in Tajikistan shooting; I’ve been to Bhutan before several times. But I didn’t shoot hospitals and traditional healthcare and early childhood development centers. These kids are shooting stories that they’ve never seen us shoot, and yet they’re using our technique, and the things that we’re teaching them, in their own way. They’re learning how to write their own recipes and cook their own soup.

Q: Do you critique their work?

A: Absolutely; every day, every single day.

Q: Are you critical? I mean, do you give them a really hard and detailed critique?

A: Yes, I do. Some people are softer. You have four instructors. When I said we divide the kids into four groups, each group has a dedicated instructor.

Q: Oh, I see. Okay.

A: Each group has a dedicated instructor and that provides two things. (1) The kids have somewhere to go instantly if they’re having a problem or if they need advice in terms of, “I can’t get this depth of field thing to work”, “I don’t know what’s the matter,” “why is everything blurry,” “why is this happening”, “why was it too light,” that kind of thing. So they can go immediately to their instructor, and that person will help them. And also, the instructor can look at what they’re doing and say, “Let me see your camera. What are you doing?”

Q: Do the instructors go out with the students and accompany them into the field?

A: Yes, into the field. That’s what they’re really there for and also to work on the edit. The other thing is that we need these groups. You can’t go into a little clinic room with more than five kids. Sometimes five kids are too many for a little room. They get in each other’s way. Dividing into these groups is really very, very important.

Q: Do you draw straws? How do you decide?

A: I sit and I say, okay, we’re going to divide up the girls and the boys and the country and the city, and we don’t want people who are friends, and…

Q: You’ve been on every single one of the workshops, correct?

A: Every one. I go to every one.

Q: Separation…

A: …convincing the mothers that it’s okay to let their daughters come with us. Then we have to show them the security measures and the chaperoning systems and so forth. I’m used to it. In fact, I know more than the NGOs do. They’re amazed. The local people are amazed that I understand their culture better than they do so that I can show them how to thread the needle.

Q: What has been the biggest surprise for you personally about this experience? I mean, did anything come about that you absolutely didn’t expect?

A: How good the kids are.

Q: Really?

A: How good the kids are. The kids are so good that…

Q: As photographers?

A: As photographers, as storytellers, as creative people . . . not just artists, but expressive artists.

Q: Do you show them celebrated and historical photo essays in class, done by other famous photographers, like Eugene Smith?

A: We show them our own work.

Q: Really? Your own work?

A: And to a certain extent they mimic our work a little bit. But the fact is that our work and the work that they’re asked to do is really different. For instance, I have a book on India. I have a book on Burma. I have a book on South Asia.

Q: I was looking at those.

A: Right.

Q: The looked great on the Internet!

A: Thank you. I’m reasonably accomplished, and I’m the only American ever to have won the Best Foreign Photographer for India award.

Q: And you do all your own editing yourself? Do you work with an editor?

A: I have people who help me—I mean, curators who will help me curate my books.

Q: Sure.

A: The fact is that I’m not in Tajikistan shooting; I’ve been to Bhutan before several times. But I didn’t shoot hospitals and traditional healthcare and early childhood development centers. These kids are shooting stories that they’ve never seen us shoot, and yet they’re using our technique, and the things that we’re teaching them, in their own way. They’re learning how to write their own recipes and cook their own soup.

Q: Do you critique their work?

A: Absolutely; every day, every single day.

Q: Are you critical? I mean, do you give them a really hard and detailed critique?

A: Yes, I do. Some people are softer. You have four instructors. When I said we divide the kids into four groups, each group has a dedicated instructor.

Q: Oh, I see. Okay.

A: Each group has a dedicated instructor and that provides two things. (1) The kids have somewhere to go instantly if they’re having a problem or if they need advice in terms of, “I can’t get this depth of field thing to work”, “I don’t know what’s the matter,” “why is everything blurry,” “why is this happening”, “why was it too light,” that kind of thing. So they can go immediately to their instructor, and that person will help them. And also, the instructor can look at what they’re doing and say, “Let me see your camera. What are you doing?”

Q: Do the instructors go out with the students and accompany them into the field?

A: Yes, into the field. That’s what they’re really there for and also to work on the edit. The other thing is that we need these groups. You can’t go into a little clinic room with more than five kids. Sometimes five kids are too many for a little room. They get in each other’s way. Dividing into these groups is really very, very important.

Q: Do you draw straws? How do you decide?

A: I sit and I say, okay, we’re going to divide up the girls and the boys and the country and the city, and we don’t want people who are friends, and…

Q: You’ve been on every single one of the workshops, correct?

A: Every one. I go to every one.

Q: And you’ve done four or five of them?

A: I’ve done eight.

Q: Oh, eight. Sorry, I thought it was less.

A: Yes, eight so far. And we’re planning to do four per year, going forward.

Q: And what are the new ones coming up?

A: We just got back from Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. Before that, we were in Bhutan for the second time. We went to Tajikistan for the second time and did an advanced workshop, and then the beginners in Kyrgyzstan. In October we’re going to Hyderabad in the south of India, and in January to do our first one in the U.S. ever.

Q: Yes, I was wondering about that, because it’s such a dynamic formula you’re working with and applying. American kids coming from inner city poverty in Detroit and a million other cities could really benefit.

A: Right. Well, we have limitations, and I’ll get to that because that’s a challenge in these workshops, as well. So let me talk about continuity, because that’s important. The formula here, as I said, is not to have a fabulous week and then walk away and leave. It’s not just leaving the cameras behind, which we do. We leave four cameras behind now, which, now that we have that many cameras, we can do. And we leave two installations of Lightroom, as I told you, so that the kids can continue to do file management.

Q: I assume that’s with computers, obviously.

A: That’s with computers that already exist there. We don’t leave them new computers. But the NGO has them, and they figure out strategically the locations for them. They figure out a sort of library lending system on the cameras, and they maintain them. But that’s not enough. We come back the following year, and we bring back the original 20 kids. And we hold a three-day really tough, no-holds-barred advanced workshop. And when you asked before how tough are the critiques; I can assure you, for that advanced class it’s as tough as any critiques at any photo course.

Q: So all-20 kids come back for the . . .

A: If we can get them. Sometimes, yes.

Q: If you can get them?

A: Yes, sometimes. There’s always something that happens.

Q: Sure, of course

A: But generally, we get all 20 kids. And…

Q: The same professors also?

A: Sometimes, but not always, because that’s another problem that we’ll talk about, which is scheduling. Scheduling is a huge problem for these workshops. So we bring them back, one of the things that distinguish the advanced from the beginning workshop is (1) the level of critique. First of all, there are no stories; there are themes. We give them a more creative environment. So instead of saying, “Today we’re going to shoot prenatal mothers in a clinic,” its - one day is nature, one day is architecture, and one day is people. And we take them to locations where they can do that.

Q: With the same basic equipment they had the first time?

A: Same exact equipment. And then we invite the NGO staff in because we have the four cameras left over from the year before, plus we have the four new cameras that we’re bringing this year. So we have 28 cameras in total. So we can invite their staff to come because what we’re really trying to do, is to create a self-generating structure that maintains itself over time. Now at the end of the three days we try and pick some of those kids who are really good as teaching assistants, and we have them join us for 20 new beginning kids who start a day later.

Q: And you’ve done four or five of them?

A: I’ve done eight.

Q: Oh, eight. Sorry, I thought it was less.

A: Yes, eight so far. And we’re planning to do four per year, going forward.

Q: And what are the new ones coming up?

A: We just got back from Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. Before that, we were in Bhutan for the second time. We went to Tajikistan for the second time and did an advanced workshop, and then the beginners in Kyrgyzstan. In October we’re going to Hyderabad in the south of India, and in January to do our first one in the U.S. ever.

Q: Yes, I was wondering about that, because it’s such a dynamic formula you’re working with and applying. American kids coming from inner city poverty in Detroit and a million other cities could really benefit.

A: Right. Well, we have limitations, and I’ll get to that because that’s a challenge in these workshops, as well. So let me talk about continuity, because that’s important. The formula here, as I said, is not to have a fabulous week and then walk away and leave. It’s not just leaving the cameras behind, which we do. We leave four cameras behind now, which, now that we have that many cameras, we can do. And we leave two installations of Lightroom, as I told you, so that the kids can continue to do file management.

Q: I assume that’s with computers, obviously.

A: That’s with computers that already exist there. We don’t leave them new computers. But the NGO has them, and they figure out strategically the locations for them. They figure out a sort of library lending system on the cameras, and they maintain them. But that’s not enough. We come back the following year, and we bring back the original 20 kids. And we hold a three-day really tough, no-holds-barred advanced workshop. And when you asked before how tough are the critiques; I can assure you, for that advanced class it’s as tough as any critiques at any photo course.

Q: So all-20 kids come back for the . . .

A: If we can get them. Sometimes, yes.

Q: If you can get them?

A: Yes, sometimes. There’s always something that happens.

Q: Sure, of course

A: But generally, we get all 20 kids. And…

Q: The same professors also?

A: Sometimes, but not always, because that’s another problem that we’ll talk about, which is scheduling. Scheduling is a huge problem for these workshops. So we bring them back, one of the things that distinguish the advanced from the beginning workshop is (1) the level of critique. First of all, there are no stories; there are themes. We give them a more creative environment. So instead of saying, “Today we’re going to shoot prenatal mothers in a clinic,” its - one day is nature, one day is architecture, and one day is people. And we take them to locations where they can do that.

Q: With the same basic equipment they had the first time?

A: Same exact equipment. And then we invite the NGO staff in because we have the four cameras left over from the year before, plus we have the four new cameras that we’re bringing this year. So we have 28 cameras in total. So we can invite their staff to come because what we’re really trying to do, is to create a self-generating structure that maintains itself over time. Now at the end of the three days we try and pick some of those kids who are really good as teaching assistants, and we have them join us for 20 new beginning kids who start a day later.

Q: That’s a great idea!