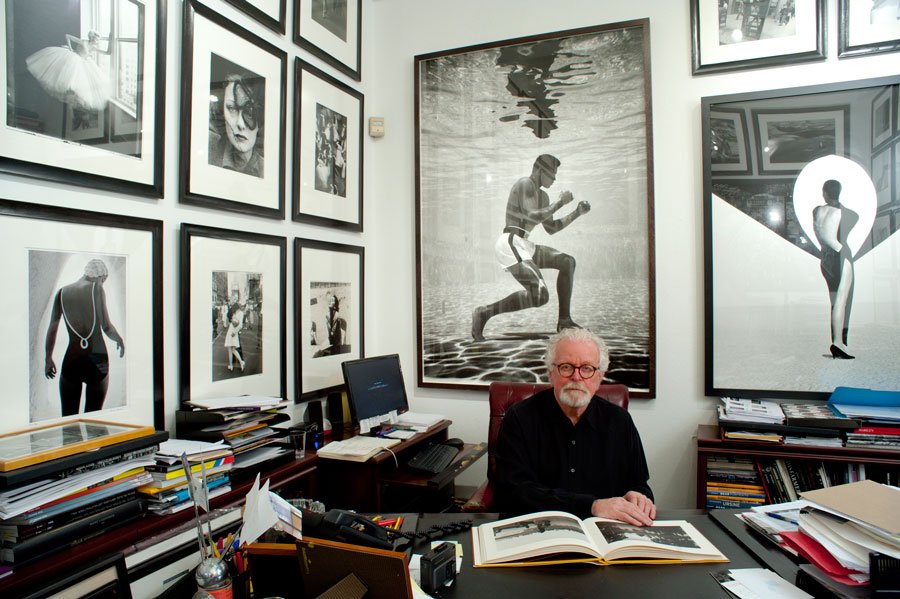

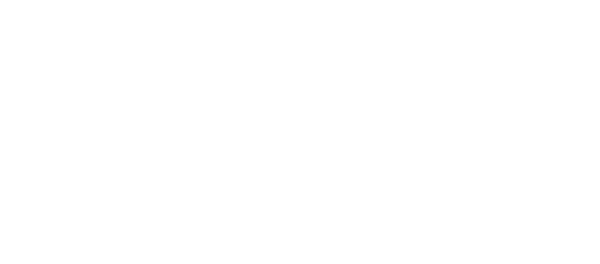

David Fahey is considered one of the most respected photo dealers in the United States. He is the director and co-owner of the Fahey-Kline gallery located on La Brea avenue in Los Angeles.  He has been exhibiting and selling fine art photography for over forty years. David Fahey has accomplished all of this with remarkable dedication, energy, and integrity.

Through the many years he had the great foresight to photograph the numerous and talented photographers he enjoyed working with, by asking each one of them to sit for a portrait- taken by him. With these timely portraits of Photographers, David Fahey has created a significant and personal body of work.

Q: Today we’re going to talk about the photographic portraits David Fahey has made of these celebrated and historically influential photographers. I wanted to ask you a few starting questions; how did this series begin? What motivated you to do it, and when did you start it?

A: Sure…. Well, I’ve been making photographs for the past 40 years. My subject matter has primarily been portraits of artists. These images that I’ve made were done during studio visits, on trips with artists, on vacations, in our Gallery or in my informal studio in the garage behind the Gallery.

AF: I remember; you photographed me there actually, many years ago.

A: Right… I have an undergraduate degree in Photo Communications; it’s Communications with an emphasis on Photography. And when I finished that I went back to school, and went through the whole Art program. This was at Cal State Fullerton, and I received a Masters of Art with an emphasis on Creative Photography.

He has been exhibiting and selling fine art photography for over forty years. David Fahey has accomplished all of this with remarkable dedication, energy, and integrity.

Through the many years he had the great foresight to photograph the numerous and talented photographers he enjoyed working with, by asking each one of them to sit for a portrait- taken by him. With these timely portraits of Photographers, David Fahey has created a significant and personal body of work.

Q: Today we’re going to talk about the photographic portraits David Fahey has made of these celebrated and historically influential photographers. I wanted to ask you a few starting questions; how did this series begin? What motivated you to do it, and when did you start it?

A: Sure…. Well, I’ve been making photographs for the past 40 years. My subject matter has primarily been portraits of artists. These images that I’ve made were done during studio visits, on trips with artists, on vacations, in our Gallery or in my informal studio in the garage behind the Gallery.

AF: I remember; you photographed me there actually, many years ago.

A: Right… I have an undergraduate degree in Photo Communications; it’s Communications with an emphasis on Photography. And when I finished that I went back to school, and went through the whole Art program. This was at Cal State Fullerton, and I received a Masters of Art with an emphasis on Creative Photography.

Q: Do you remember who your professors were?

A: It was Darryl Curran, Eileen Cowin.

AF: Interesting…all locals…

A: Yes, all locals- I initially went to a junior college and then I dropped out for a semester figuring I needed to make some money, because I had an apartment in Belmont Shores and figured by the time the Draft Board caught up to me (during the Vietnam war) I would be back in school, that was my initial plan. But what happened right after I dropped out, within two weeks I got a draft notice. And so, I got drafted. So when I finished my service in Vietnam, I came back and you could get out a little early if you were going back to college, so then I enrolled to go to Cal State Fullerton.

Q: So what year were you actually in Viet Nam?

A: I was in Viet Nam in 1969 and ’70.

Q: And were you in the Army?

A: I was in the Army, the 25th Infantry. We were kind of stationed up along the Cambodian border. We were in the jungle; I mean we were not in a base or anything. We were kind of in the middle of nowhere. That was in 1969. And then, you know, a little army history. We were the first unit into Cambodia, when Nixon—

Q: Was that legal or illegal then?

A: It was legal because it was the time when there was an excursion into Cambodia and they were bombing Cambodia for a month in May. We were the first to actually enter into Cambodia. And that’s when Kent State happened; it was protesting that invasion.

AF: I remember that really well. The killing of Students at Kent State, by the National Guardsmen, was a shocking tragedy.

A: And so it really was an invasion of sorts, and it was a very different situation in those days because the Viet Cong- they were entrenched in Cambodia because they weren’t expecting to be attacked. And so, it was a different scene in Cambodia than it was in Viet Nam in those years- because it was a lot more intense.

Q: Did you take any pictures while you were in Vietnam?

A: Yes… I have a number of snap shots I took there, but I wasn’t there as a photographer, I just for some reason, I had taken my camera and I managed to take some pictures.

Q: Do you have a recollection of the first, in a sense, serious portrait that you did of a photographer? What year might that have been, or around when? What would you guess, late ‘60s, early ‘70s?

A: Well I was photographing—you know, during this whole time before Vietnam and after Vietnam, so I’d go to the Troubadour nightclub in West Hollywood and I photographed musicians, because I was a musician. And I went up to Doug Weston, who was the owner of the Troubadour and said, “If I can get in free I’ll photograph the musicians for you.” And he said, “Absolutely.” He took me downstairs and introduced me to the ticket girl and the manager.

AF: Boy, how times have changed…

A: Yeah… And he said, “This guy gets in for free”. And so, I lived across the street on Rangeley, which is the street south of Melrose but right below the Troubadour. On every Wednesday and Thursday night, when the acts were all opening, I would go over there. And sometimes major acts like Bonnie Raitt and Jackson Browne performed there. Sometimes I would be there and there’d be 30 people in the audience, and so I went to all of these shows and I photographed. Of course I got in before everybody, so I sat right in the front, near center stage and photographed them all.

[caption id="attachment_2134" align="aligncenter" width="600"]

Q: Do you remember who your professors were?

A: It was Darryl Curran, Eileen Cowin.

AF: Interesting…all locals…

A: Yes, all locals- I initially went to a junior college and then I dropped out for a semester figuring I needed to make some money, because I had an apartment in Belmont Shores and figured by the time the Draft Board caught up to me (during the Vietnam war) I would be back in school, that was my initial plan. But what happened right after I dropped out, within two weeks I got a draft notice. And so, I got drafted. So when I finished my service in Vietnam, I came back and you could get out a little early if you were going back to college, so then I enrolled to go to Cal State Fullerton.

Q: So what year were you actually in Viet Nam?

A: I was in Viet Nam in 1969 and ’70.

Q: And were you in the Army?

A: I was in the Army, the 25th Infantry. We were kind of stationed up along the Cambodian border. We were in the jungle; I mean we were not in a base or anything. We were kind of in the middle of nowhere. That was in 1969. And then, you know, a little army history. We were the first unit into Cambodia, when Nixon—

Q: Was that legal or illegal then?

A: It was legal because it was the time when there was an excursion into Cambodia and they were bombing Cambodia for a month in May. We were the first to actually enter into Cambodia. And that’s when Kent State happened; it was protesting that invasion.

AF: I remember that really well. The killing of Students at Kent State, by the National Guardsmen, was a shocking tragedy.

A: And so it really was an invasion of sorts, and it was a very different situation in those days because the Viet Cong- they were entrenched in Cambodia because they weren’t expecting to be attacked. And so, it was a different scene in Cambodia than it was in Viet Nam in those years- because it was a lot more intense.

Q: Did you take any pictures while you were in Vietnam?

A: Yes… I have a number of snap shots I took there, but I wasn’t there as a photographer, I just for some reason, I had taken my camera and I managed to take some pictures.

Q: Do you have a recollection of the first, in a sense, serious portrait that you did of a photographer? What year might that have been, or around when? What would you guess, late ‘60s, early ‘70s?

A: Well I was photographing—you know, during this whole time before Vietnam and after Vietnam, so I’d go to the Troubadour nightclub in West Hollywood and I photographed musicians, because I was a musician. And I went up to Doug Weston, who was the owner of the Troubadour and said, “If I can get in free I’ll photograph the musicians for you.” And he said, “Absolutely.” He took me downstairs and introduced me to the ticket girl and the manager.

AF: Boy, how times have changed…

A: Yeah… And he said, “This guy gets in for free”. And so, I lived across the street on Rangeley, which is the street south of Melrose but right below the Troubadour. On every Wednesday and Thursday night, when the acts were all opening, I would go over there. And sometimes major acts like Bonnie Raitt and Jackson Browne performed there. Sometimes I would be there and there’d be 30 people in the audience, and so I went to all of these shows and I photographed. Of course I got in before everybody, so I sat right in the front, near center stage and photographed them all.

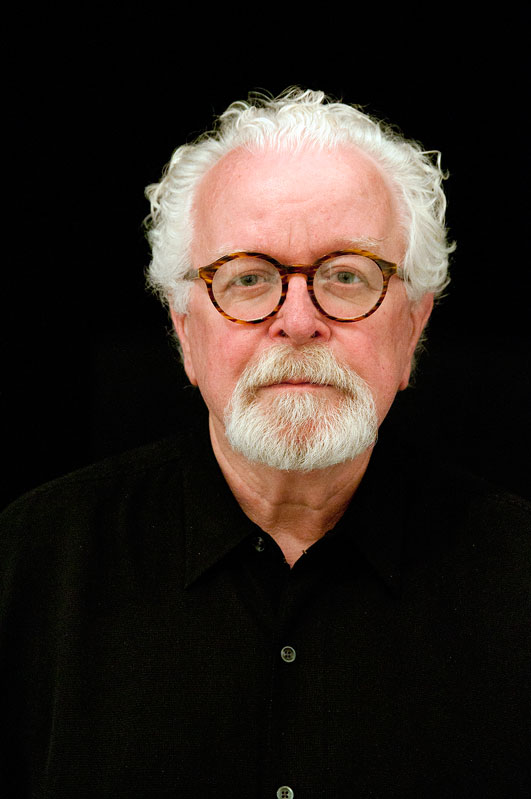

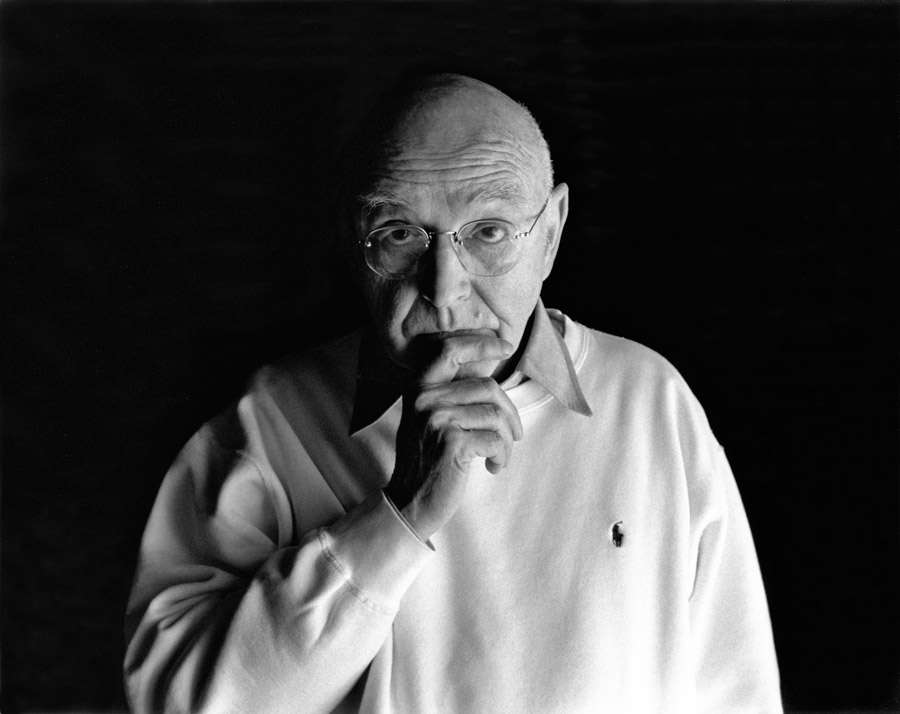

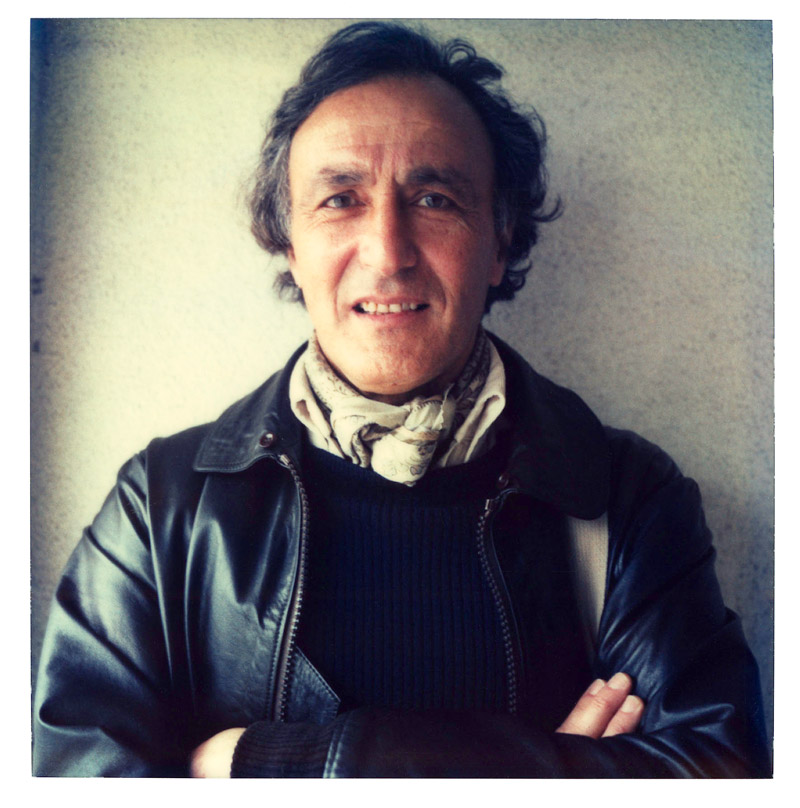

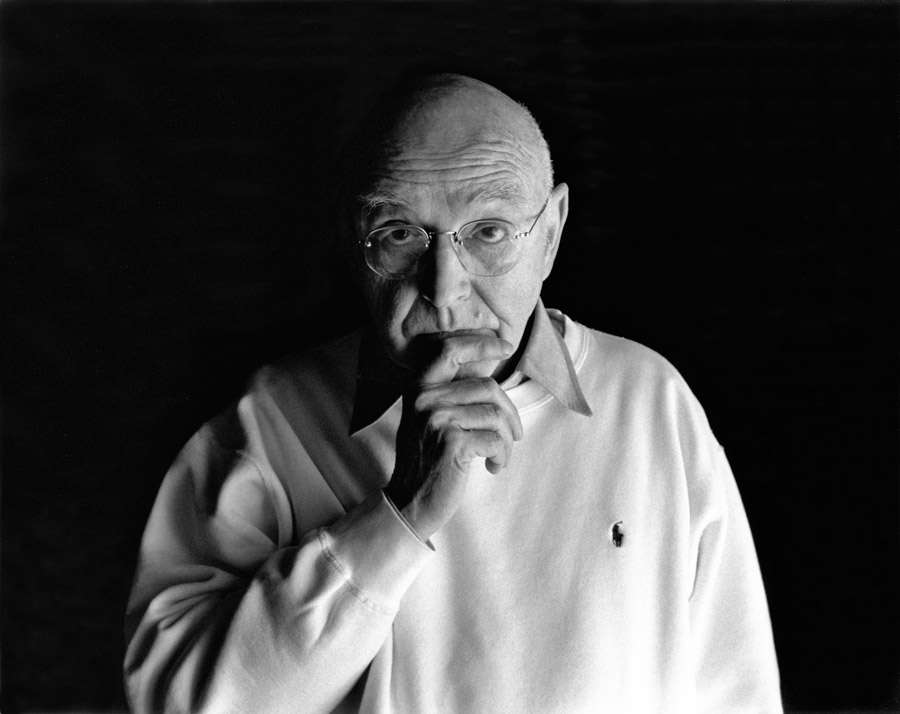

[caption id="attachment_2134" align="aligncenter" width="600"] Portrait of Peter Beard by David Fahey[/caption]

Q: Do you still have the negatives from any of those sessions?

A: I have all that stuff somewhere in my garage. And so, I was doing that before I went to Vietnam and even after I got back.

AF: How nice.

A: I wish I had made better pictures and I wish I’d have gone backstage, you know, upstairs where the musicians hung out. I was a little timid maybe back in those days. I didn’t want to be intrusive and I felt I was lucky to do what I got to do and I didn’t want to get in the way. But, I got to practice my photography skills. So, my first pictures were -

Q: And those were not easy situations to shoot in, with the stage lighting, right?

A: Back in those days you were shooting film, it’s all low light, sometimes there was no light, and it was just difficult all the time.

Q: Do you remember the first photographer you actually, kind of seriously, did a portrait of?

A: Very good question.

Q: Or a couple that may come to mind perhaps?

A: Yes…it would have been when I was in graduate school, I started working at the G. Ray Hawkins Gallery, and after a month I was made the Director of Contemporary Photography at the G. Ray Hawkins Gallery. There were many photographers that were coming in and passing through. And so at that time, what I did is, I just decided well- you know, I always never knew what Brett Weston looked like or—

AF: Or a lot of them…

A: A lot of them. I didn’t know Lee Witkin, who was a dealer, the first LA dealer—and all these people; I didn’t know what they looked like. And so, I thought, well, I’m going to take pictures of these people because maybe someday, down the road, people will want to know what they looked like- back in those days.

AF: Of course…

A: And so, I started to take them outside, in front of the door of the gallery, because it was sort of a plain backdrop and I would shoot SX70 Polaroid portraits. And so I did a whole series of these.

Q: So, what year are we talking about?

A: This was in the ’70’s, from ’75 to ’83, probably. I shot from ’75 to ’80 at the Melrose location, down by Café Figaro. And then from ’80 to ’83 or ’84, we did them at the newer space, at the other end of Melrose, close to La Brea ave. It just became a regular thing I would do with the photographers. What I did is, I did one portrait of them- that I took- that was a head and shoulders shot, straight on. And then I said, “okay, I want you to set up the next picture, you tell me how you want me to photograph you and give me your camera pose”, that was sort of the idea; my interpretation of how I was photographing, and their interpretation of how they wanted me to photograph them. Everybody’s different. Irving Penn for example, his two pictures look exactly the same because the idea was in the first picture; he knew exactly how he wanted it to look. The second picture, he knew exactly how he wanted to look; it was the same. Avedon, the first picture I took was different than the one he set up which was he had me move in closer, he put his glasses up on his forehead and that was the picture, and so, each one was a little different. Now, when you look at the whole series, you really don’t notice a big difference between the first and the second pictures.

Q: Did you pretty much stay with that method, throughout all the different sessions, over all the years?

A: Yes… There were two backdrops; the front of the door and then at the other space I did shoot in this little entryway, because it had good side- light. You’ll see in the pictures.

[caption id="attachment_2149" align="aligncenter" width="600"]

Portrait of Peter Beard by David Fahey[/caption]

Q: Do you still have the negatives from any of those sessions?

A: I have all that stuff somewhere in my garage. And so, I was doing that before I went to Vietnam and even after I got back.

AF: How nice.

A: I wish I had made better pictures and I wish I’d have gone backstage, you know, upstairs where the musicians hung out. I was a little timid maybe back in those days. I didn’t want to be intrusive and I felt I was lucky to do what I got to do and I didn’t want to get in the way. But, I got to practice my photography skills. So, my first pictures were -

Q: And those were not easy situations to shoot in, with the stage lighting, right?

A: Back in those days you were shooting film, it’s all low light, sometimes there was no light, and it was just difficult all the time.

Q: Do you remember the first photographer you actually, kind of seriously, did a portrait of?

A: Very good question.

Q: Or a couple that may come to mind perhaps?

A: Yes…it would have been when I was in graduate school, I started working at the G. Ray Hawkins Gallery, and after a month I was made the Director of Contemporary Photography at the G. Ray Hawkins Gallery. There were many photographers that were coming in and passing through. And so at that time, what I did is, I just decided well- you know, I always never knew what Brett Weston looked like or—

AF: Or a lot of them…

A: A lot of them. I didn’t know Lee Witkin, who was a dealer, the first LA dealer—and all these people; I didn’t know what they looked like. And so, I thought, well, I’m going to take pictures of these people because maybe someday, down the road, people will want to know what they looked like- back in those days.

AF: Of course…

A: And so, I started to take them outside, in front of the door of the gallery, because it was sort of a plain backdrop and I would shoot SX70 Polaroid portraits. And so I did a whole series of these.

Q: So, what year are we talking about?

A: This was in the ’70’s, from ’75 to ’83, probably. I shot from ’75 to ’80 at the Melrose location, down by Café Figaro. And then from ’80 to ’83 or ’84, we did them at the newer space, at the other end of Melrose, close to La Brea ave. It just became a regular thing I would do with the photographers. What I did is, I did one portrait of them- that I took- that was a head and shoulders shot, straight on. And then I said, “okay, I want you to set up the next picture, you tell me how you want me to photograph you and give me your camera pose”, that was sort of the idea; my interpretation of how I was photographing, and their interpretation of how they wanted me to photograph them. Everybody’s different. Irving Penn for example, his two pictures look exactly the same because the idea was in the first picture; he knew exactly how he wanted it to look. The second picture, he knew exactly how he wanted to look; it was the same. Avedon, the first picture I took was different than the one he set up which was he had me move in closer, he put his glasses up on his forehead and that was the picture, and so, each one was a little different. Now, when you look at the whole series, you really don’t notice a big difference between the first and the second pictures.

Q: Did you pretty much stay with that method, throughout all the different sessions, over all the years?

A: Yes… There were two backdrops; the front of the door and then at the other space I did shoot in this little entryway, because it had good side- light. You’ll see in the pictures.

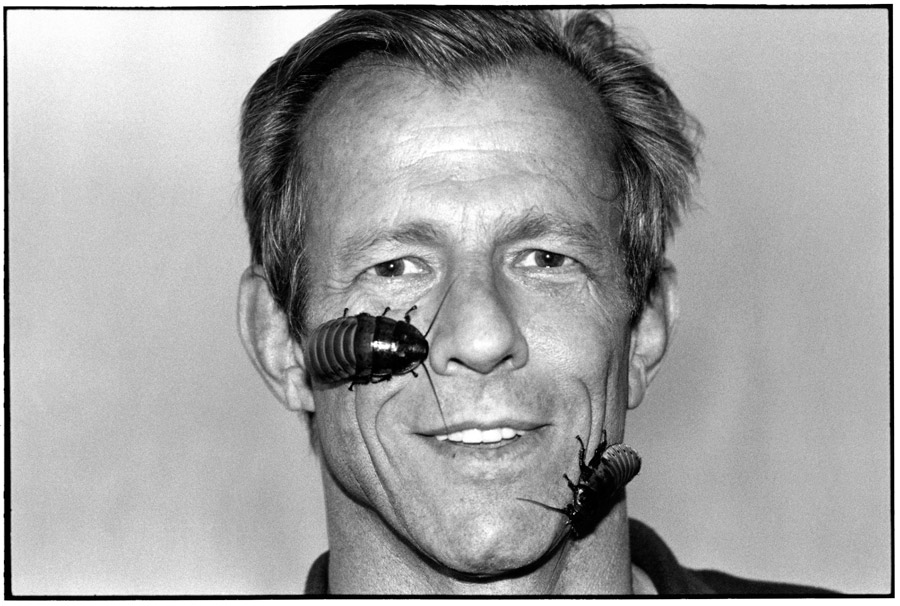

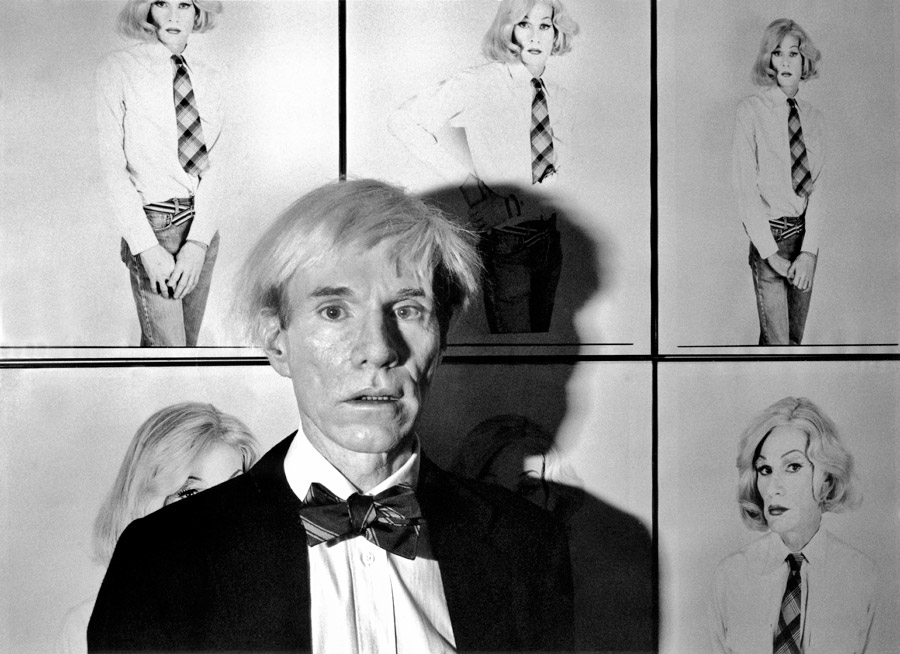

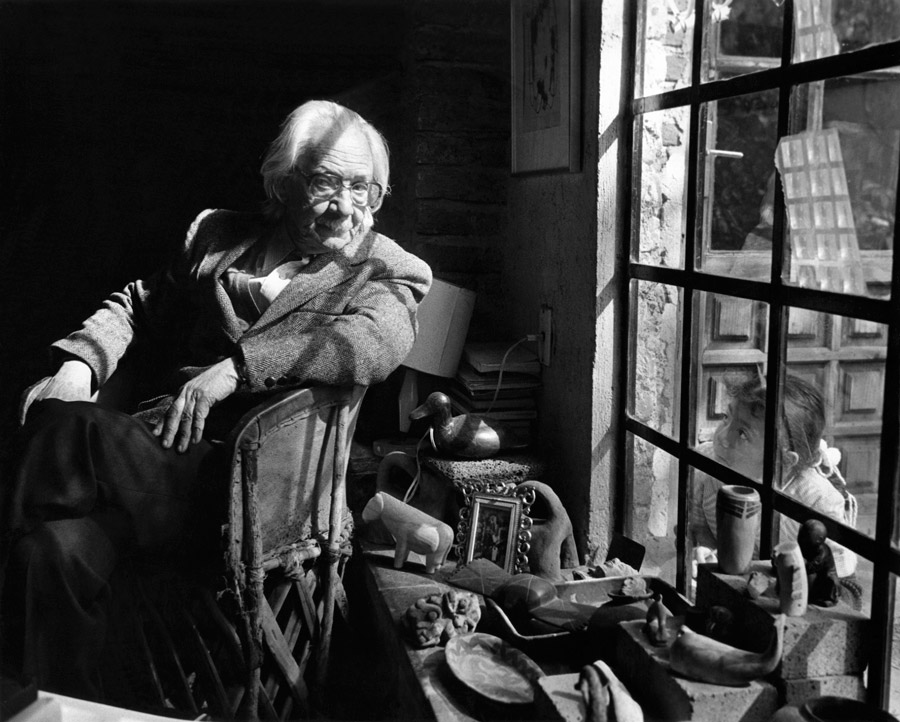

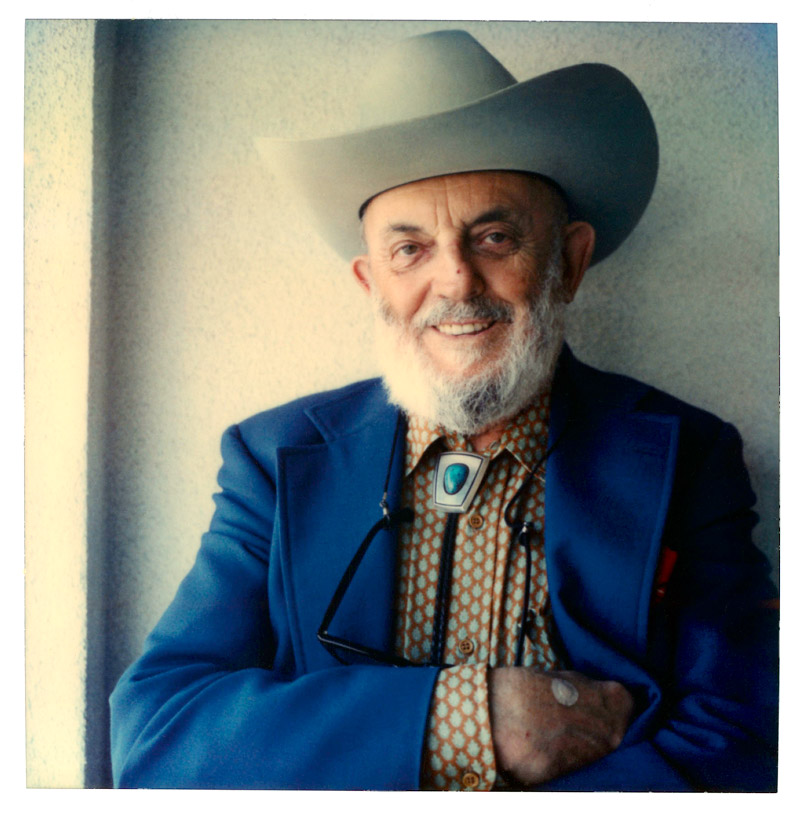

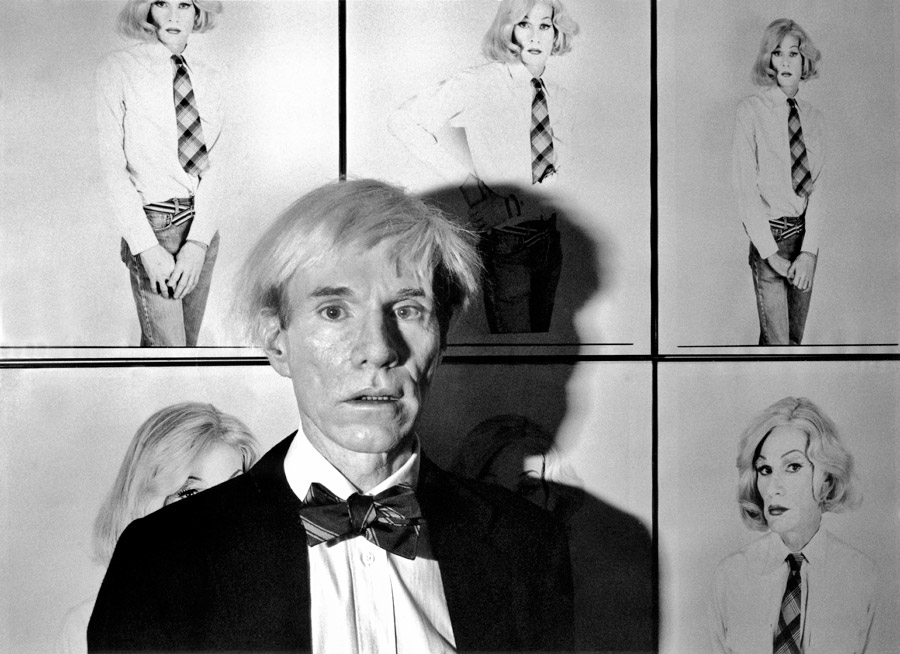

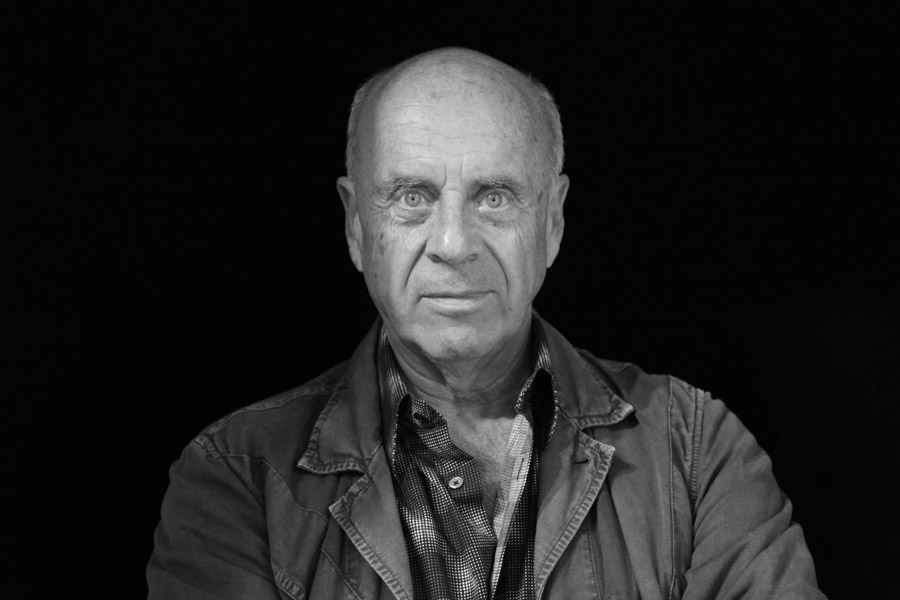

[caption id="attachment_2149" align="aligncenter" width="600"] Portrait of Andy Warhol by David Fahey[/caption]

Q: You know, I’ve been thinking about the questions I wanted to pose to you today, and I was wondering, more in a general sense, because you’ve been involved now for so many years with really significant photographers, I was wondering if you feel there exists some connective tissue, some commonality, some thread that runs through the personalities of all these extraordinary photographers? The ones you’ve been photographing through the years. Do you feel there is something that connects all of us? Is there something that you could describe, that you would say you could put your finger on? Like, they all share a certain…character trait?

A: Well, all creative people have the same kind of sensibility, I think, in that they’re curious people, they’re engaging. They want to explore and they’re very—can be provocative as personalities. Some people are quiet that way and some people are kind of passive-aggressive that way and then some people are in your face that way. But the commonality would be this very intriguing kind of person that was in front of my camera, for example--

Q: Like a certain dynamic?

A: A dynamic, some kind of quality, they were picture-makers. They knew what the cameras could do and they knew how they wanted to look in front of the cameras. Most of them were very aware of being photographed, certainly, because that’s their business and they know what that whole process means. And I was deliberately—I never said I want to do a picture of you tomorrow. So, I never wanted to give them an advance notice that they were going to be photographed. I wanted to be very spontaneous and I wanted it to be—every picture I made was an experiment. I never tried—even though it sounds formulaic at the beginning, later on I wanted it to be very spontaneous because I didn’t want them to prepare or to worry about it, or dress a certain way. I just wanted them to be as they are. And so, as I say, I always mention, it was not setting out to make a picture, it was not me, hair and makeup and an assistant for a half-a-day or a day shooting somewhere in a great location. It was me… with five minutes—

AF: One-on-one.

A: One-on-one, a grab shot. I was using whatever light I could. You know, I even photographed people in the bathroom here. I photographed people in the garage. I photographed people on vacation when we were just going somewhere, in the airport for example, or whatever it was, or if I visited their home. So, it was all very different in that way, to try to catch them—

Q: Were most of the photographers agreeable? Did any of them say, no, I want to go home and change? Did any of them say I’m not comfortable with this?

A: No… you know it’s funny, but oddly enough I don’t think there’s one photographer that really disagreed, because I’m not very confrontational and I don’t think I come off as threatening and problematic— And I think, actually when people meet you—I believe this too—when they meet you, within a few minutes they know whether or not they can trust you or not. If you have a conversation with them they know, “I’m going to trust this guy or I’m not.” And, of course, some of them I had longer relationships and more established relationships with. Some of them I’d met and in five minutes I said, “Hey, let me take your picture.” But I think intuitively they knew, hey, I could trust this guy. He’s not going to do something crazy and make me look ridiculous.

Q: When you met a photographer whose work that you were familiar with, before you actually met them, it could be a super famous photographer or maybe someone not that well-known, but you knew of their work, when you met them did you feel or find that their personalities matched their work in some way, that there was a clear relationship between what kind of a personality they had and the kinds of photographs that they made? I mean, I guess the question also is two-sided. Did you ever meet any of them that you felt were really quite different than what you anticipated they might be like or were very, very different? For example, when you met Peter-Joel Witkin, were you surprised at his personality or the instincts that you had about what kind of person he was or did you have a preconceived idea? Because he’s kind of dark, I mean, he’s got some very dark images.

A: The answer is both. I mean, I had a preconceived idea of who he was and what he was about because I had researched him. And then, of course, when you have the actual encounter, it’s a whole different experience; there are all new things. There are some aspects you don’t—there are nuances that you don’t see and you can’t read about- that you absorb once you’re in front of that person. The other little piece of information—and this is something you know—was that for, I don’t know, three or four years as Hawkins’ Gallery I did this photo bulletin. So—do you remember that?

[caption id="attachment_2135" align="alignright" width="205"]

Portrait of Andy Warhol by David Fahey[/caption]

Q: You know, I’ve been thinking about the questions I wanted to pose to you today, and I was wondering, more in a general sense, because you’ve been involved now for so many years with really significant photographers, I was wondering if you feel there exists some connective tissue, some commonality, some thread that runs through the personalities of all these extraordinary photographers? The ones you’ve been photographing through the years. Do you feel there is something that connects all of us? Is there something that you could describe, that you would say you could put your finger on? Like, they all share a certain…character trait?

A: Well, all creative people have the same kind of sensibility, I think, in that they’re curious people, they’re engaging. They want to explore and they’re very—can be provocative as personalities. Some people are quiet that way and some people are kind of passive-aggressive that way and then some people are in your face that way. But the commonality would be this very intriguing kind of person that was in front of my camera, for example--

Q: Like a certain dynamic?

A: A dynamic, some kind of quality, they were picture-makers. They knew what the cameras could do and they knew how they wanted to look in front of the cameras. Most of them were very aware of being photographed, certainly, because that’s their business and they know what that whole process means. And I was deliberately—I never said I want to do a picture of you tomorrow. So, I never wanted to give them an advance notice that they were going to be photographed. I wanted to be very spontaneous and I wanted it to be—every picture I made was an experiment. I never tried—even though it sounds formulaic at the beginning, later on I wanted it to be very spontaneous because I didn’t want them to prepare or to worry about it, or dress a certain way. I just wanted them to be as they are. And so, as I say, I always mention, it was not setting out to make a picture, it was not me, hair and makeup and an assistant for a half-a-day or a day shooting somewhere in a great location. It was me… with five minutes—

AF: One-on-one.

A: One-on-one, a grab shot. I was using whatever light I could. You know, I even photographed people in the bathroom here. I photographed people in the garage. I photographed people on vacation when we were just going somewhere, in the airport for example, or whatever it was, or if I visited their home. So, it was all very different in that way, to try to catch them—

Q: Were most of the photographers agreeable? Did any of them say, no, I want to go home and change? Did any of them say I’m not comfortable with this?

A: No… you know it’s funny, but oddly enough I don’t think there’s one photographer that really disagreed, because I’m not very confrontational and I don’t think I come off as threatening and problematic— And I think, actually when people meet you—I believe this too—when they meet you, within a few minutes they know whether or not they can trust you or not. If you have a conversation with them they know, “I’m going to trust this guy or I’m not.” And, of course, some of them I had longer relationships and more established relationships with. Some of them I’d met and in five minutes I said, “Hey, let me take your picture.” But I think intuitively they knew, hey, I could trust this guy. He’s not going to do something crazy and make me look ridiculous.

Q: When you met a photographer whose work that you were familiar with, before you actually met them, it could be a super famous photographer or maybe someone not that well-known, but you knew of their work, when you met them did you feel or find that their personalities matched their work in some way, that there was a clear relationship between what kind of a personality they had and the kinds of photographs that they made? I mean, I guess the question also is two-sided. Did you ever meet any of them that you felt were really quite different than what you anticipated they might be like or were very, very different? For example, when you met Peter-Joel Witkin, were you surprised at his personality or the instincts that you had about what kind of person he was or did you have a preconceived idea? Because he’s kind of dark, I mean, he’s got some very dark images.

A: The answer is both. I mean, I had a preconceived idea of who he was and what he was about because I had researched him. And then, of course, when you have the actual encounter, it’s a whole different experience; there are all new things. There are some aspects you don’t—there are nuances that you don’t see and you can’t read about- that you absorb once you’re in front of that person. The other little piece of information—and this is something you know—was that for, I don’t know, three or four years as Hawkins’ Gallery I did this photo bulletin. So—do you remember that?

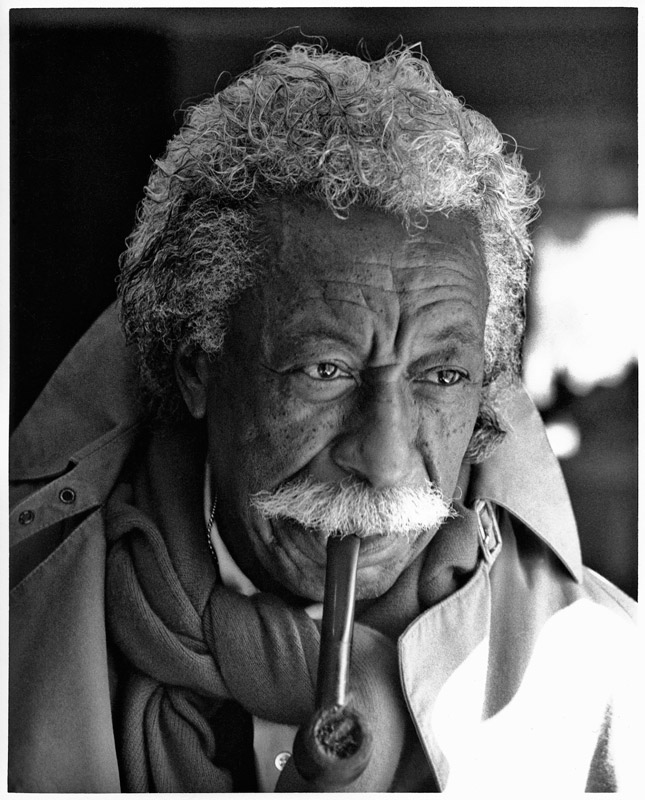

[caption id="attachment_2135" align="alignright" width="205"] Portrait of Harry Benson by David Fahey[/caption]

AF: Yes, I was in it.

A: And so, I did—that’s right.

AF: You wrote one about me.

A: Yes… I did very intensive research and I wrote an original biography on every person.

AF: I remember that.

A: They were brief. I did research so I kind of knew their personalities beforehand. And I do a great deal of reading, so I knew whom these people were, even before I met them.

Q: Any dramatic surprises on any of them?

A: Not really, I mean, I would say in answer to your question, I’d say the quieter photographers make quieter pictures, you know. That would be the only real kind of notable observation I could make about that. You know, more methodical, quiet, studied pictures as opposed to someone who needs a very vibrant personality in order to make fashion photographs or editorial portraits

AF: Like Harry Benson for example?

A: Yes, like Harry, or anybody that’s working with the public on a regular basis, needs to be engaging and creative and very inventive.

AF: And obviously someone like the great rock & roll photographer Jim Marshall…

A: Yes, like Jim Marshall or any of those photographers that worked with a broad range of personalities, they have to have a certain-without question- have a certain kind of quality. I’ve always been intrigued by artists and their images and how they actually looked. In the beginning, I felt others might also be interested in how these individuals appear and present themselves in front of the camera as well. I set out to photograph and make an encyclopedic record of my time and experiences in the world of photography. And getting back to what I said earlier and something that Francis Bacon said, “that chance and accidents are the most fertile things at any artist’s disposal.” And so, I would deliberately try to create a situation where it was going to be a spontaneous, a chance kind of encounter.

AF: Which is very intuitive …

A: Yes, and so you’re just—capturing a certain serendipity, it was one of my objectives. Most of these portraits were made spontaneously. No assistants and no preconceived planning and very little time. I enjoyed working within these parameters; I felt that was the most exciting and challenging part. It was a problem I had to solve. I always welcomed the challenge to capture the spirit and personality of these unique subjects.

Q: Were there times you felt that you wanted to go back and do it again, that you missed something?

A: Oh yeah.

Q: And did you have many opportunities where you actually could go back and try another setup?

[caption id="attachment_2147" align="alignleft" width="200"]

Portrait of Harry Benson by David Fahey[/caption]

AF: Yes, I was in it.

A: And so, I did—that’s right.

AF: You wrote one about me.

A: Yes… I did very intensive research and I wrote an original biography on every person.

AF: I remember that.

A: They were brief. I did research so I kind of knew their personalities beforehand. And I do a great deal of reading, so I knew whom these people were, even before I met them.

Q: Any dramatic surprises on any of them?

A: Not really, I mean, I would say in answer to your question, I’d say the quieter photographers make quieter pictures, you know. That would be the only real kind of notable observation I could make about that. You know, more methodical, quiet, studied pictures as opposed to someone who needs a very vibrant personality in order to make fashion photographs or editorial portraits

AF: Like Harry Benson for example?

A: Yes, like Harry, or anybody that’s working with the public on a regular basis, needs to be engaging and creative and very inventive.

AF: And obviously someone like the great rock & roll photographer Jim Marshall…

A: Yes, like Jim Marshall or any of those photographers that worked with a broad range of personalities, they have to have a certain-without question- have a certain kind of quality. I’ve always been intrigued by artists and their images and how they actually looked. In the beginning, I felt others might also be interested in how these individuals appear and present themselves in front of the camera as well. I set out to photograph and make an encyclopedic record of my time and experiences in the world of photography. And getting back to what I said earlier and something that Francis Bacon said, “that chance and accidents are the most fertile things at any artist’s disposal.” And so, I would deliberately try to create a situation where it was going to be a spontaneous, a chance kind of encounter.

AF: Which is very intuitive …

A: Yes, and so you’re just—capturing a certain serendipity, it was one of my objectives. Most of these portraits were made spontaneously. No assistants and no preconceived planning and very little time. I enjoyed working within these parameters; I felt that was the most exciting and challenging part. It was a problem I had to solve. I always welcomed the challenge to capture the spirit and personality of these unique subjects.

Q: Were there times you felt that you wanted to go back and do it again, that you missed something?

A: Oh yeah.

Q: And did you have many opportunities where you actually could go back and try another setup?

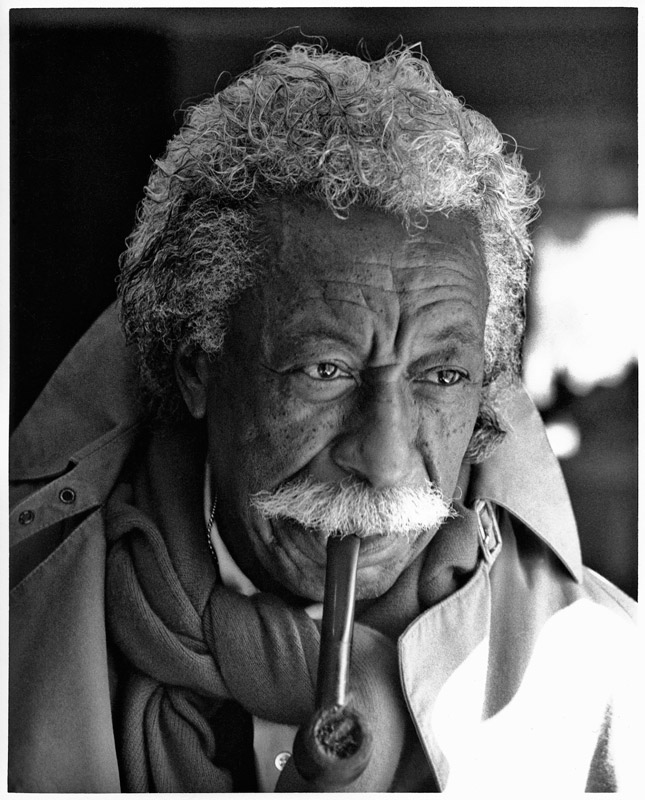

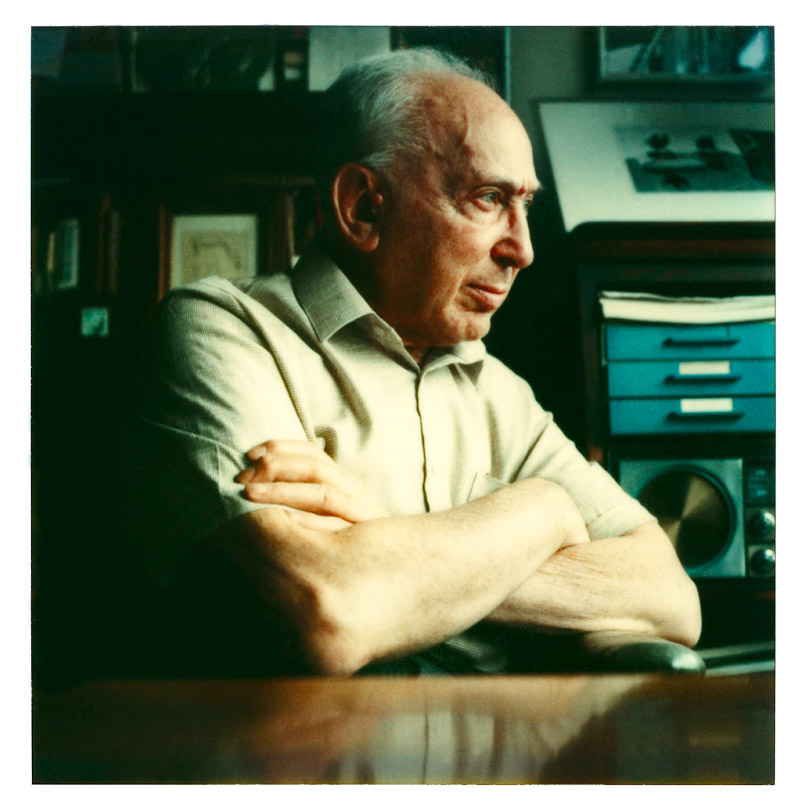

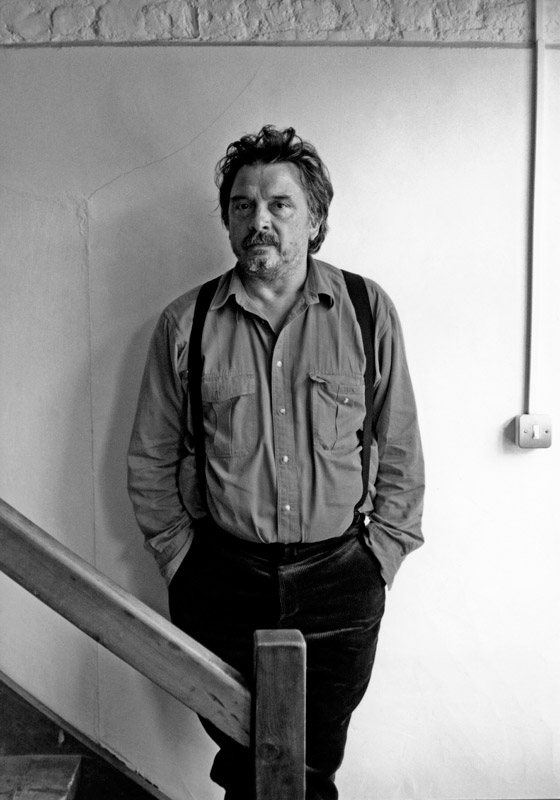

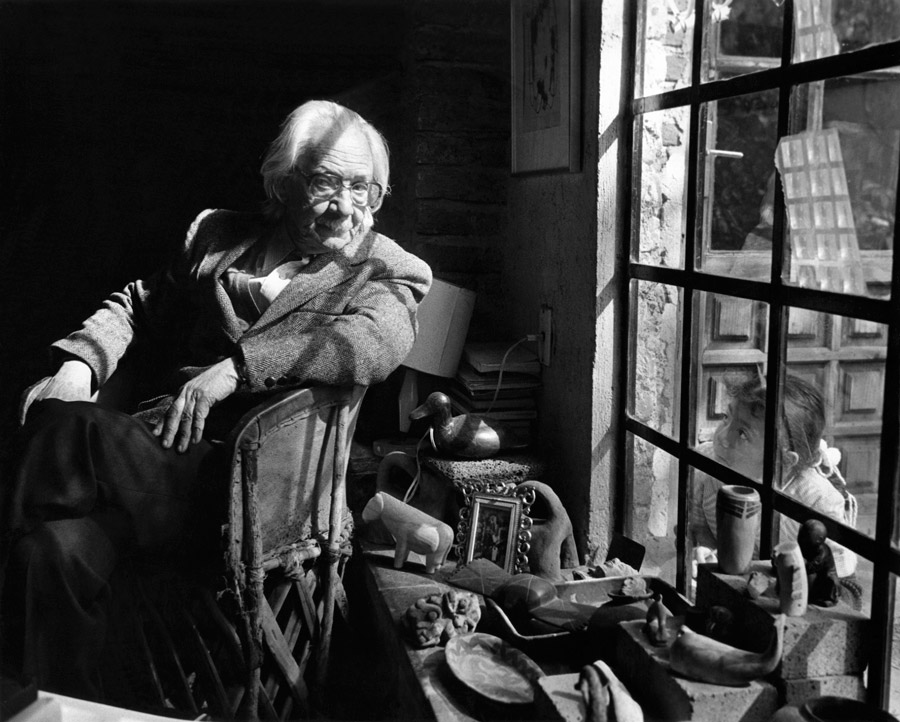

[caption id="attachment_2147" align="alignleft" width="200"] Portrait of Gordon Parks by David Fahey[/caption]

A: Yes and no. Once again, it’s what I said earlier, that every photograph was an experiment. I always loved using different cameras, and so I would frequently do that. And sometimes I wouldn’t be as adept as I could have been with a camera, and so my exposures were a little funky or I could have done something a little differently to make the pictures a little better technically. But then I thought, well, you know, it’s not about making them perfect. It’s about making them. It’s about the time and the moment. And so, I just sort of embraced that variable that changed from time to time. You know, a powerful portrait is created with cooperation and it’s the collaboration between the subject and the photographer. Each responds to signals from the other. The ability to give and receive these signals determines the success of the sitting. The way a person stands or sits often discloses the way a person thinks, thus revealing the posture of the mind.

[caption id="attachment_2133" align="alignright" width="200"]

Portrait of Gordon Parks by David Fahey[/caption]

A: Yes and no. Once again, it’s what I said earlier, that every photograph was an experiment. I always loved using different cameras, and so I would frequently do that. And sometimes I wouldn’t be as adept as I could have been with a camera, and so my exposures were a little funky or I could have done something a little differently to make the pictures a little better technically. But then I thought, well, you know, it’s not about making them perfect. It’s about making them. It’s about the time and the moment. And so, I just sort of embraced that variable that changed from time to time. You know, a powerful portrait is created with cooperation and it’s the collaboration between the subject and the photographer. Each responds to signals from the other. The ability to give and receive these signals determines the success of the sitting. The way a person stands or sits often discloses the way a person thinks, thus revealing the posture of the mind.

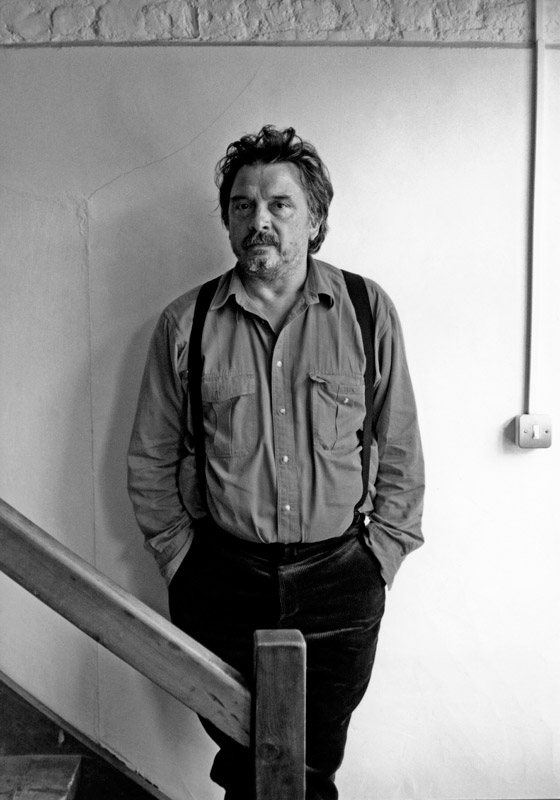

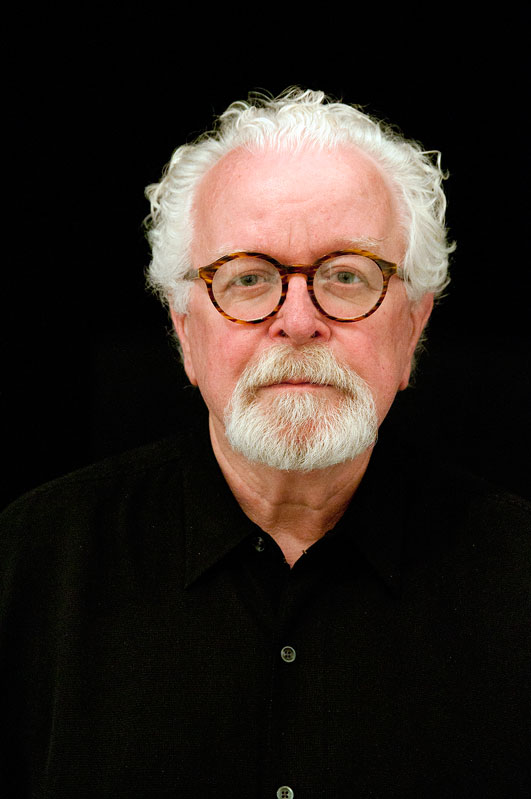

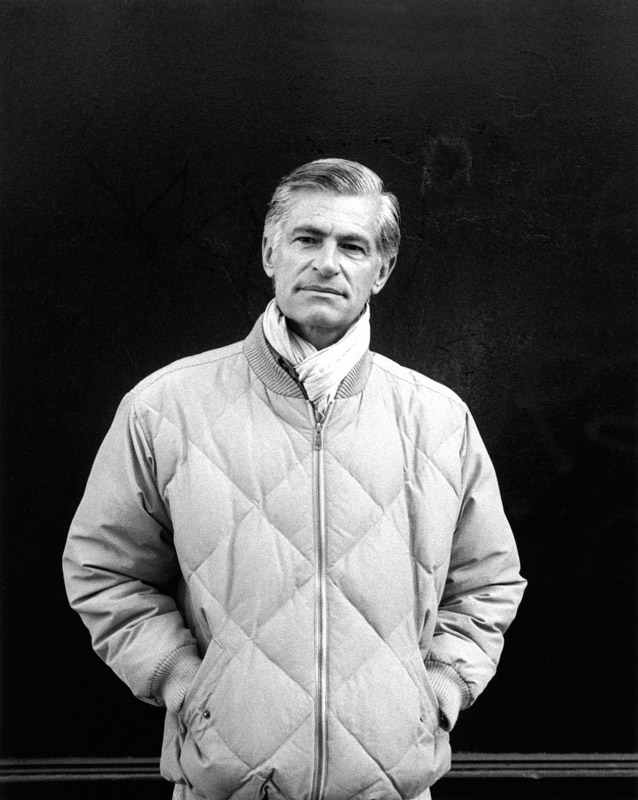

[caption id="attachment_2133" align="alignright" width="200"] Portrait of David Bailey by David Fahey[/caption]

Q: I was curious about something. Did you find through the years, the photographers you did portraits of, did they enjoy talking about and explaining their process? Were some very guarded and others much more open about that? Or did you find, in general, that most of them were excited about talking about their work and enjoyed it?

A: Well, I never did that when I was actually taking the pictures, because I was really focused on me getting what I needed to get, and so it was a conversation, an engagement I could have with them that might relate to their pictures, but not always. It could just relate to the moment we were in or what we were doing that night or if we were going out to dinner or whatever it was, in the course of my making pictures.

Q: Well, certain artists are comfortable talking about their process. I was just wondering in general, because over all the different photographers you’ve worked with, have you found that a lot of them celebrated that? That they enjoyed talking about their process? Or were they were very guarded about it?

A: Well, some could talk about it, and would, and some had difficulty discussing their process. You know how it is, most visual artists, their standard line is, “Let the work speak for itself.”

AF: Well, ultimately that is true…

[caption id="attachment_2145" align="alignleft" width="200"]

Portrait of David Bailey by David Fahey[/caption]

Q: I was curious about something. Did you find through the years, the photographers you did portraits of, did they enjoy talking about and explaining their process? Were some very guarded and others much more open about that? Or did you find, in general, that most of them were excited about talking about their work and enjoyed it?

A: Well, I never did that when I was actually taking the pictures, because I was really focused on me getting what I needed to get, and so it was a conversation, an engagement I could have with them that might relate to their pictures, but not always. It could just relate to the moment we were in or what we were doing that night or if we were going out to dinner or whatever it was, in the course of my making pictures.

Q: Well, certain artists are comfortable talking about their process. I was just wondering in general, because over all the different photographers you’ve worked with, have you found that a lot of them celebrated that? That they enjoyed talking about their process? Or were they were very guarded about it?

A: Well, some could talk about it, and would, and some had difficulty discussing their process. You know how it is, most visual artists, their standard line is, “Let the work speak for itself.”

AF: Well, ultimately that is true…

[caption id="attachment_2145" align="alignleft" width="200"] Portrait of James Nachtwey by David Fahey[/caption]

A: Yes, that is true, but what would happen is-you know when I was doing interviews with them, sure, we would get into that in a big way and I would try to penetrate that veil as much as I could, and actually if you have a very non-assertive response that’s really revealing in and of itself too. And so, I kind of liked to play with that, quite a bit in terms of my interviewing. And I’ve done probably 80 interviews with photographers.

Q: When making decisions over which photographs you would select, to go along with the interview you had done about them, what criteria would you use? What would drive your personal choices about your own work?

A: You mean the edit?

AF: Well, I also want to talk about how you have said- that you, personally, have found that photographers are notoriously horrible at editing their own work.

A: Oh… for sure.

AF: I want to talk about that, because it’s a very interesting observation you’ve made. I was wondering what basis you make that conclusion from?

A: I guess it’s based on the fact that I’ve been a dealer since 1975. I’ve worked with artists; I’ve done over 50 books. I’ve edited and sequenced over 50 books. I’ve edited and sequenced probably 1,000 exhibitions, major exhibitions and I’ve done them, you know, in different locations.

Q: A thousand, really? Over 1,000 exhibitions?

A: At least a thousand, yes… I mean, I think I introduced, and this is something I figured out maybe seven, eight years ago—that I had shown and introduced over 500, 600 artists—this was like seven years ago. But in terms of exhibitions, I’ve done even more--you know, it’s like anything, if you do something 1,000 times you get pretty good at it. It’s just unavoidable. You just become a little bit of an expert about that. And so, it’s like sequencing the show we have on now. Nobody could have sequenced them better; it’s just the best it could ever be sequenced, period. And I’ve had artists come in and say, “Oh, I want to switch this around, I want to do this,” and inevitably they go back to what I selected originally, because it’s just the best sequencing for the art work. You know, it’s just how it works, and that just comes from experience. But your question was about editing.

Q: When you went over your contact sheets, looking over the portraits you did of the different photographers, inspecting them frame by frame, did you select by instinct? Did you pick the picture you thought was the most visually interesting? Or select the one you thought revealed their character better than the other ones, or all the above?

A: Yes. The thing is, that I’ve always said, is that most photographers are bad editors of their work; not all, but many. And some are very sharp and right on it, dead on every time.

[caption id="attachment_2150" align="alignright" width="233"]

Portrait of James Nachtwey by David Fahey[/caption]

A: Yes, that is true, but what would happen is-you know when I was doing interviews with them, sure, we would get into that in a big way and I would try to penetrate that veil as much as I could, and actually if you have a very non-assertive response that’s really revealing in and of itself too. And so, I kind of liked to play with that, quite a bit in terms of my interviewing. And I’ve done probably 80 interviews with photographers.

Q: When making decisions over which photographs you would select, to go along with the interview you had done about them, what criteria would you use? What would drive your personal choices about your own work?

A: You mean the edit?

AF: Well, I also want to talk about how you have said- that you, personally, have found that photographers are notoriously horrible at editing their own work.

A: Oh… for sure.

AF: I want to talk about that, because it’s a very interesting observation you’ve made. I was wondering what basis you make that conclusion from?

A: I guess it’s based on the fact that I’ve been a dealer since 1975. I’ve worked with artists; I’ve done over 50 books. I’ve edited and sequenced over 50 books. I’ve edited and sequenced probably 1,000 exhibitions, major exhibitions and I’ve done them, you know, in different locations.

Q: A thousand, really? Over 1,000 exhibitions?

A: At least a thousand, yes… I mean, I think I introduced, and this is something I figured out maybe seven, eight years ago—that I had shown and introduced over 500, 600 artists—this was like seven years ago. But in terms of exhibitions, I’ve done even more--you know, it’s like anything, if you do something 1,000 times you get pretty good at it. It’s just unavoidable. You just become a little bit of an expert about that. And so, it’s like sequencing the show we have on now. Nobody could have sequenced them better; it’s just the best it could ever be sequenced, period. And I’ve had artists come in and say, “Oh, I want to switch this around, I want to do this,” and inevitably they go back to what I selected originally, because it’s just the best sequencing for the art work. You know, it’s just how it works, and that just comes from experience. But your question was about editing.

Q: When you went over your contact sheets, looking over the portraits you did of the different photographers, inspecting them frame by frame, did you select by instinct? Did you pick the picture you thought was the most visually interesting? Or select the one you thought revealed their character better than the other ones, or all the above?

A: Yes. The thing is, that I’ve always said, is that most photographers are bad editors of their work; not all, but many. And some are very sharp and right on it, dead on every time.

[caption id="attachment_2150" align="alignright" width="233"] Portrait of Joel Peter Witkin by David Fahey[/caption]

Q: Like whom for example?

A: Well, Herb Ritts was very good.

Q: Herb was?

A: Yes, Herb was very good. He was completely on it. And Joel-Peter Witkin is someone who is really particular about his selections, a very good editor- he knows how to do it as well. And you can name a whole list of people. But generally, many photographers miss great pictures. You can go through contact sheets and find a great picture of theirs and they go, “well, I didn’t think that was anything” and that becomes the biggest selling picture that they’ve ever had. I can tell you, Steve Shapiro for example, I found one of his biggest selling pictures that he never printed before and it became a very successful picture. You know, I edited that first book of Steve’s. And so, the photographers, you know, you’re close to the images and you have a different criteria and you’re seeing it and looking at it from a different perspective. And so, you’re not really—and also you maybe shot it for a magazine, but the picture that’s really more revealing is the one that doesn’t get used by the magazine. And so it’s a matter of going back and looking and really examining everything. Now, when I make that statement about most photographers don’t have the ability to do that, I’m including myself. If I’m anything, I’m an editor and I know how to edit and I know how to edit other people’s work very well. I can do that. I’m very good at that. But editing my own work, that situation falls under the same--

Q: So, you fall into the similar trap?

A: I fall into the similar trap. I have a connection to every one of those pictures and I have a perception about which ones work best for me. But when I look through my pictures, I’m saying to myself, “I’ve got to have my son come over and look at these and help me edit them because I can’t pick the best one.” And that’s why when I got a request to send some for a blog, it said, “I need 15 pictures,” I sent them 100 pictures. I can’t pick; pick whatever you think works. I think it really is particular to the photographer, including myself.

Q: I was wondering, of all the photographers who have prevailed in the long history of the medium, going back to the invention of photography in the early 1830’s, including all the ones that have passed away; The ones you never would have had a chance to photograph because they’re deceased, which photographers in history would you have loved to have been able to take their portrait? —like, people say, that if you had a chance to sit down to dinner with any famous person throughout human history, whom would you have wanted to sit down with? What photographers would you have desired to meet and photograph?

A: I would say Nadar, who was a portrait photographer, a famous portrait photographer in France in the 19th century. But I would also say Cartier-Bresson, Robert Frank, there’s a whole list of them.

AF: Well, Frank’s still around.

A: Yes, I know. It’s hard to kind of go up to him and say, hey, I want to photograph you; but Cartier-Bresson, certainly. You know, other artists also—because I never really made a distinction between a photographer as an artist, and other visual artists, like painters. They’re all artists and creative people to me, and I’d love to have photographed Francis Bacon or Lucian Freud, they would have been great. Less so Picasso, but certainly if I’d had the opportunity Picasso would be great. But the reality is I photographed a lot of photographers. So, I mean, Man Ray would be another one I would love to have photographed.

Q: How important… for example, the great portrait photographers- some of them specialized in sports figures, some specialized in musicians, some specialized in models or fashion, some doing street portraits, how important do you think it is for a photographer to know something about what they’re photographing? Do you think it gives their work an additional dimension? Like, when Avedon did the American West pictures, he didn’t know any of those people personally, or what their lives were honestly about, but he makes these assumptions rather rapidly about them, when he choose to release the shutter. He was so gifted as a portrait photographer…I think he worked with his instincts, don’t you? Certainly he had some idea of what the people he photographed did, or what they were defined by.

A: I mean, they always have said, and you read this, that a portrait is really a portrait of the photographer. The photograph he makes of someone else is really a revealing portrait of the photographer. And like, with Steve Sharpiro, it’s really about what his interests are as a person, and it is Civil Rights and it is photographing on the street. With Avedon, it’s—he made Navy portraits on a white backdrop in his early career—I’m pretty sure this is the case—like passport-type photographs.

AF: Yes, he went through the Navy’s photo training school, his American West photos have a white backdrop as well… very interesting parallel.

[caption id="attachment_2144" align="aligncenter" width="600"]

Portrait of Joel Peter Witkin by David Fahey[/caption]

Q: Like whom for example?

A: Well, Herb Ritts was very good.

Q: Herb was?

A: Yes, Herb was very good. He was completely on it. And Joel-Peter Witkin is someone who is really particular about his selections, a very good editor- he knows how to do it as well. And you can name a whole list of people. But generally, many photographers miss great pictures. You can go through contact sheets and find a great picture of theirs and they go, “well, I didn’t think that was anything” and that becomes the biggest selling picture that they’ve ever had. I can tell you, Steve Shapiro for example, I found one of his biggest selling pictures that he never printed before and it became a very successful picture. You know, I edited that first book of Steve’s. And so, the photographers, you know, you’re close to the images and you have a different criteria and you’re seeing it and looking at it from a different perspective. And so, you’re not really—and also you maybe shot it for a magazine, but the picture that’s really more revealing is the one that doesn’t get used by the magazine. And so it’s a matter of going back and looking and really examining everything. Now, when I make that statement about most photographers don’t have the ability to do that, I’m including myself. If I’m anything, I’m an editor and I know how to edit and I know how to edit other people’s work very well. I can do that. I’m very good at that. But editing my own work, that situation falls under the same--

Q: So, you fall into the similar trap?

A: I fall into the similar trap. I have a connection to every one of those pictures and I have a perception about which ones work best for me. But when I look through my pictures, I’m saying to myself, “I’ve got to have my son come over and look at these and help me edit them because I can’t pick the best one.” And that’s why when I got a request to send some for a blog, it said, “I need 15 pictures,” I sent them 100 pictures. I can’t pick; pick whatever you think works. I think it really is particular to the photographer, including myself.

Q: I was wondering, of all the photographers who have prevailed in the long history of the medium, going back to the invention of photography in the early 1830’s, including all the ones that have passed away; The ones you never would have had a chance to photograph because they’re deceased, which photographers in history would you have loved to have been able to take their portrait? —like, people say, that if you had a chance to sit down to dinner with any famous person throughout human history, whom would you have wanted to sit down with? What photographers would you have desired to meet and photograph?

A: I would say Nadar, who was a portrait photographer, a famous portrait photographer in France in the 19th century. But I would also say Cartier-Bresson, Robert Frank, there’s a whole list of them.

AF: Well, Frank’s still around.

A: Yes, I know. It’s hard to kind of go up to him and say, hey, I want to photograph you; but Cartier-Bresson, certainly. You know, other artists also—because I never really made a distinction between a photographer as an artist, and other visual artists, like painters. They’re all artists and creative people to me, and I’d love to have photographed Francis Bacon or Lucian Freud, they would have been great. Less so Picasso, but certainly if I’d had the opportunity Picasso would be great. But the reality is I photographed a lot of photographers. So, I mean, Man Ray would be another one I would love to have photographed.

Q: How important… for example, the great portrait photographers- some of them specialized in sports figures, some specialized in musicians, some specialized in models or fashion, some doing street portraits, how important do you think it is for a photographer to know something about what they’re photographing? Do you think it gives their work an additional dimension? Like, when Avedon did the American West pictures, he didn’t know any of those people personally, or what their lives were honestly about, but he makes these assumptions rather rapidly about them, when he choose to release the shutter. He was so gifted as a portrait photographer…I think he worked with his instincts, don’t you? Certainly he had some idea of what the people he photographed did, or what they were defined by.

A: I mean, they always have said, and you read this, that a portrait is really a portrait of the photographer. The photograph he makes of someone else is really a revealing portrait of the photographer. And like, with Steve Sharpiro, it’s really about what his interests are as a person, and it is Civil Rights and it is photographing on the street. With Avedon, it’s—he made Navy portraits on a white backdrop in his early career—I’m pretty sure this is the case—like passport-type photographs.

AF: Yes, he went through the Navy’s photo training school, his American West photos have a white backdrop as well… very interesting parallel.

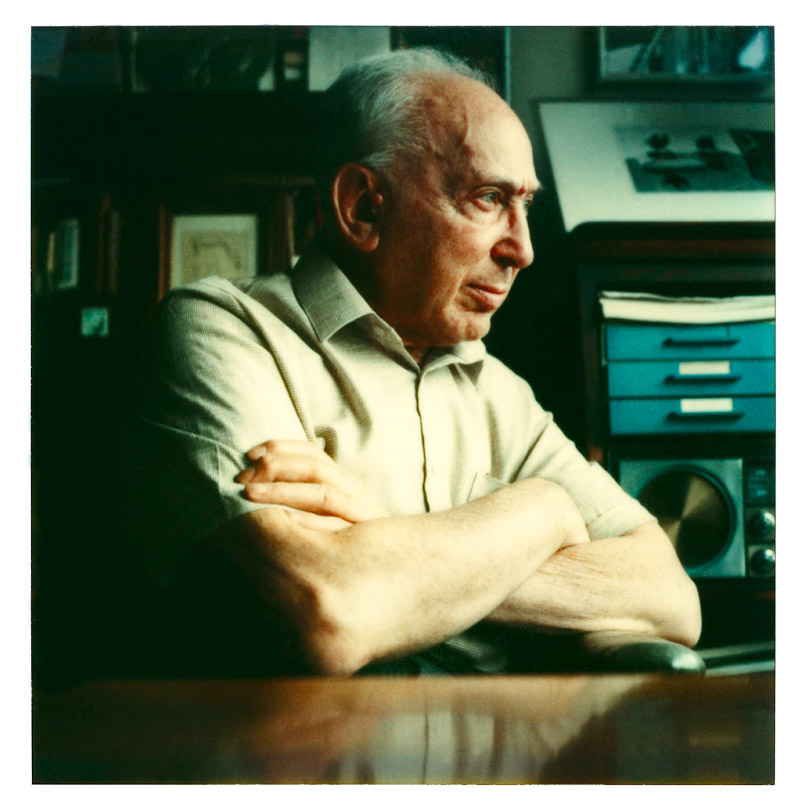

[caption id="attachment_2144" align="aligncenter" width="600"] Portrait of Duane Michals by David Fahey[/caption]

A: He went through that whole kind of area. Well, he makes pictures that are kind of like his personality, in a way. Penn is the same thing, it’s very controlled, precise, very Swedish aesthetic, if you will, I mean that kind of quiet, cold, precise, direct, beautiful image. And Peter Beard is, of course, a real free spirit and his pictures are such. Garry Winogrand on the street- he’s always moving, and I always thought he kind of maneuvered and moved like a shark. He’s always moving and taking pictures, and he was like that, so as a consequence, they’re very spontaneous photographers.

[caption id="attachment_2141" align="aligncenter" width="600"]

Portrait of Duane Michals by David Fahey[/caption]

A: He went through that whole kind of area. Well, he makes pictures that are kind of like his personality, in a way. Penn is the same thing, it’s very controlled, precise, very Swedish aesthetic, if you will, I mean that kind of quiet, cold, precise, direct, beautiful image. And Peter Beard is, of course, a real free spirit and his pictures are such. Garry Winogrand on the street- he’s always moving, and I always thought he kind of maneuvered and moved like a shark. He’s always moving and taking pictures, and he was like that, so as a consequence, they’re very spontaneous photographers.

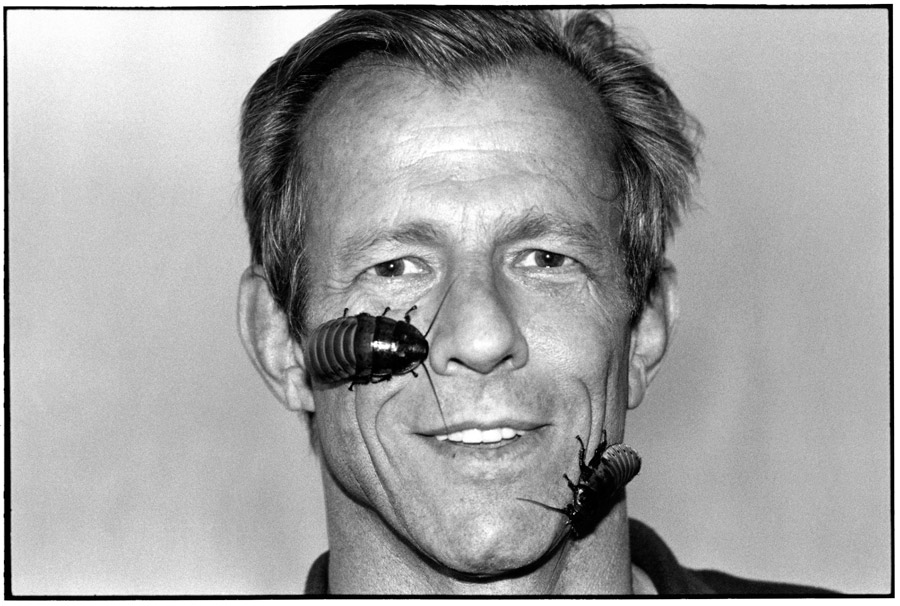

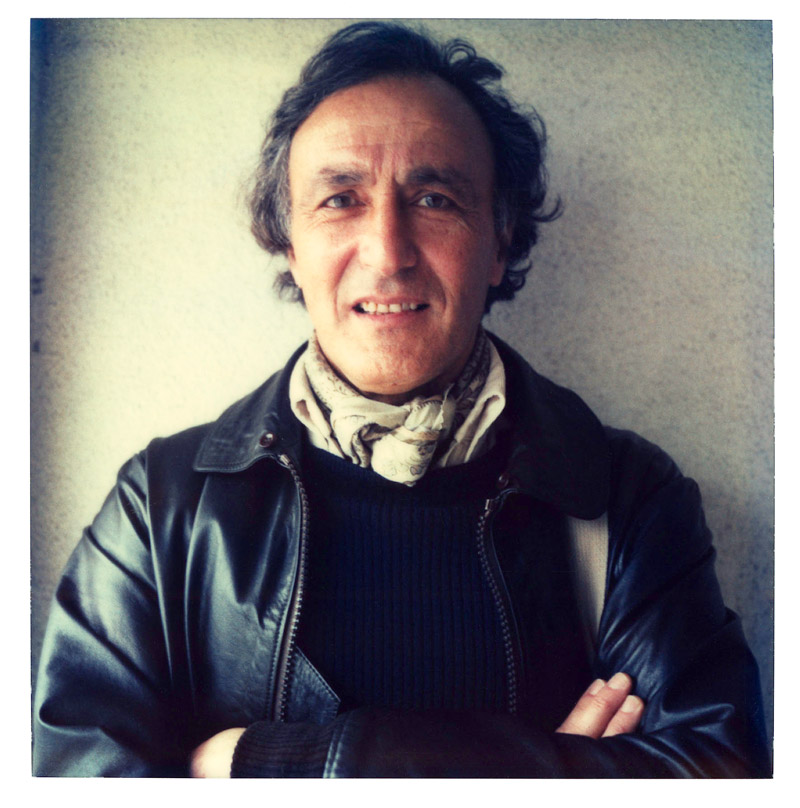

[caption id="attachment_2141" align="aligncenter" width="600"] Portrait of Ralph Gibson by David Fahey[/caption]

Q: I know, because we all appeared in the same exhibit together, I was wondering what it was like for you to hang out with Garry Winogrand? When you guys photographed at the Ivar Theater together, which was a notorious strip club in Hollywood that allowed photographers to come in and photograph the girls while they were stripping and posing totally naked for the audience. What was that like hanging out with him and going to a strip club?

A: Well you know, we were friends first and photographers second, I think. And so, it wasn’t like we were friends because we were involved in photography, although that’s how it came to be, but we were social friends. I mean, we were personal friends, I guess is the word. And then photography was a backdrop to a great deal of what we did together. You know, I would go with him to the Edwards Air Force Base air shows and we’d photograph or we would—only occasionally we photographed on the streets of Hollywood. And then I found this club—because I was still in graduate school, I think—I found this club that I started photographing in and then I thought Garry would love to photograph there also, so I took Garry. And then Garry introduced the club to Bill Dane and a few other people. And the other people then ended up going there and photographing. But yes, we would have lunch, I guess once a week for three or four years. Garry and I would go have lunch and just talk about everything from politics to—you know, it was never like, hey, what’s going on with the photographic thing? That was the subject and we discussed it and talked about it but it wasn’t the primary subject by any means. We talked about our families, growing up, having kids, dealing with people.

AF: It really was a genuine friendship.

A: Yes, it was just a genuine friendship and I think Garry was the kind of personality, as you know, he either liked you or didn’t, and if he didn’t like you he just didn’t hang out with you. If he liked you, you could hang out with him. There was one other thing about Garry, I was trying to think, that was kind of interesting. He—you know, was just really engaging, incredibly smart guy. And I was drawn to him just because of his intelligence. He was perceptive and smart as an observer and he really was aware of what was going on and he could see behind the story, so to speak, and he could make those connections. And so, when you talked about anything, he would have this point of view that was incredibly interesting. And so, I gravitated towards that; I just thought that’s the greatest thing. And so I really, whenever we could get together, I would do it.

Q: What was Andre Kertesz like? When you met Kertesz?

A: Kertesz was like- and this was much later in his life when he was older and living In New York. It was at his apartment, it was a studio visit and he was just very quiet and very old-world, cordial and proper and, you know, proper etiquette. And we just had nice conversations. I wish I would have taped it or recorded it or something; it was just kind of a conversation about photography and what was going on. And then I said, “Hey, I make these Polaroids. Can I make a picture of you?” And he said, “Sure.” And so, I made these pictures. And he said, “Well now, I have to take pictures of you.” And I said, “Absolutely.” He took my camera, took two or three pictures of me and then he signed them.

[caption id="attachment_2136" align="alignleft" width="212"]

Portrait of Ralph Gibson by David Fahey[/caption]

Q: I know, because we all appeared in the same exhibit together, I was wondering what it was like for you to hang out with Garry Winogrand? When you guys photographed at the Ivar Theater together, which was a notorious strip club in Hollywood that allowed photographers to come in and photograph the girls while they were stripping and posing totally naked for the audience. What was that like hanging out with him and going to a strip club?

A: Well you know, we were friends first and photographers second, I think. And so, it wasn’t like we were friends because we were involved in photography, although that’s how it came to be, but we were social friends. I mean, we were personal friends, I guess is the word. And then photography was a backdrop to a great deal of what we did together. You know, I would go with him to the Edwards Air Force Base air shows and we’d photograph or we would—only occasionally we photographed on the streets of Hollywood. And then I found this club—because I was still in graduate school, I think—I found this club that I started photographing in and then I thought Garry would love to photograph there also, so I took Garry. And then Garry introduced the club to Bill Dane and a few other people. And the other people then ended up going there and photographing. But yes, we would have lunch, I guess once a week for three or four years. Garry and I would go have lunch and just talk about everything from politics to—you know, it was never like, hey, what’s going on with the photographic thing? That was the subject and we discussed it and talked about it but it wasn’t the primary subject by any means. We talked about our families, growing up, having kids, dealing with people.

AF: It really was a genuine friendship.

A: Yes, it was just a genuine friendship and I think Garry was the kind of personality, as you know, he either liked you or didn’t, and if he didn’t like you he just didn’t hang out with you. If he liked you, you could hang out with him. There was one other thing about Garry, I was trying to think, that was kind of interesting. He—you know, was just really engaging, incredibly smart guy. And I was drawn to him just because of his intelligence. He was perceptive and smart as an observer and he really was aware of what was going on and he could see behind the story, so to speak, and he could make those connections. And so, when you talked about anything, he would have this point of view that was incredibly interesting. And so, I gravitated towards that; I just thought that’s the greatest thing. And so I really, whenever we could get together, I would do it.

Q: What was Andre Kertesz like? When you met Kertesz?

A: Kertesz was like- and this was much later in his life when he was older and living In New York. It was at his apartment, it was a studio visit and he was just very quiet and very old-world, cordial and proper and, you know, proper etiquette. And we just had nice conversations. I wish I would have taped it or recorded it or something; it was just kind of a conversation about photography and what was going on. And then I said, “Hey, I make these Polaroids. Can I make a picture of you?” And he said, “Sure.” And so, I made these pictures. And he said, “Well now, I have to take pictures of you.” And I said, “Absolutely.” He took my camera, took two or three pictures of me and then he signed them.

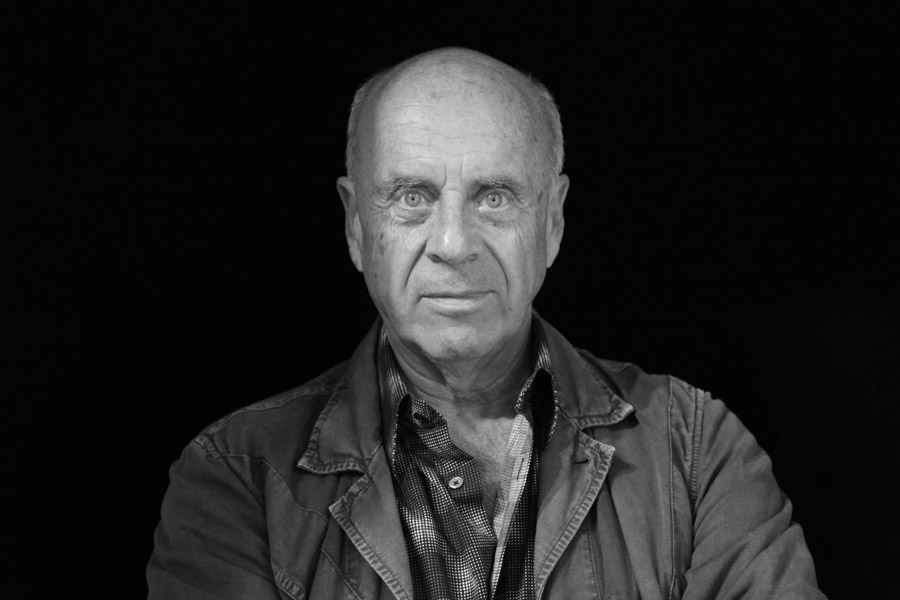

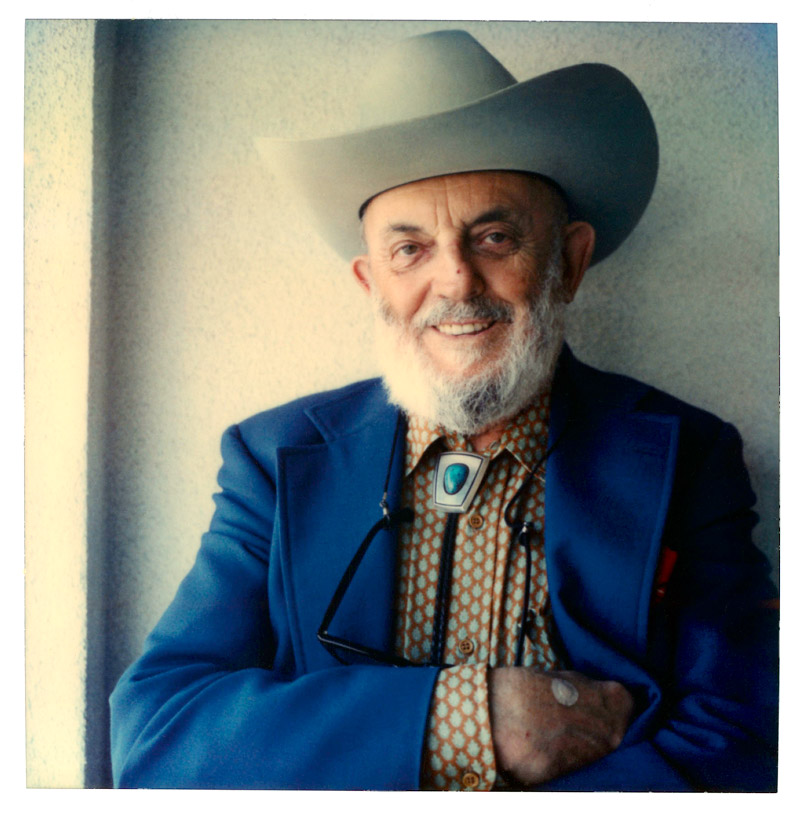

[caption id="attachment_2136" align="alignleft" width="212"] Portrait of Manuel Alvarez-Bravo by David Fahey[/caption]

AF: Wow…

A: Which was pretty wild, and he signed them and that was kind of my memory of our encounter. And of course, we did business with Kertesz over the years and so we had that kind of relationship.

Q: Did you ever photograph Josef Koudelka?

A: Yes.

AF: Well, I remember we came into your gallery one day together.

A: Yes and I photographed him sitting on that couch. Yeah, I don’t think he liked it.

AF: Oh, he is shy. I have a number of portraits I’ve taken of him.

A: I have, actually—it’s not a bad picture of him.

AF: And Cartier Bresson was shy also. I photographed Bresson in his Paris apartment—

A: Yes, see I’d love to have been able to photograph Bresson.

AF: But, I mean, I never got like a one-on-one, looking into the lens kind of a portrait, but I have Bresson working with Robert Delpire when they were laying out one of his books in Bresson’s apartment. They had a bunch of 5x7s-prints on the floor that they were sequencing and I was just like, kind of like a fly on the wall, just pulled back and took my shot.

A: That’s what you have to do; that’s what you have to do. I always thought—sometimes I thought maybe if I did that when I was meeting them as a gallerist that it would be like an intrusion or an opportunistic kind of thing because all of a sudden I’d pull out my camera and take a picture. Only one person turned me down to take their picture and that was Sarah Moon, she said “No, lets do it tomorrow”, which regretfully never happened.

Q: Do you think there’s a way to define what makes a great portrait in a photograph? I mean, do you think there are certain things that have to be met or accomplished, in a sense? For you, what makes a great photographic portrait?

A: Well, it’s a lot of different things, but I think the time and the place are two very important things because my pictures are my pictures and—let me read here from one of my diaries—“every time I make a picture I know this moment will never come again, there is something historical, creative and exciting about documenting the faces of talented individual artists who, in some cases, change the way we think and interpret our lives.” In my view, art is whatever changes you, transforms your thinking and makes you re-calibrate your perception.

AF: Amen, amen.

A: Yes, and I’m looking at someone who is capable of that. And so, now I have to make a picture of them. And so, I believe the interesting qualities, whatever they may be, are inherent in the gesture, the posture, the pose, the eyes, the face, the way they look into the camera, the way they look away from the camera, I think it’s all there. And I think it’s there for that moment, at that time, and it could be a little different tomorrow, in another place, in another time, what not. But I think it’s my opportunity to really capture that moment and I think with my pictures, you know, an aspect that you can’t deny is that as much as I would like to think that they’re all incredible pictures, a part of their interest lies in the fact that it’s now 30 years later and these people came from photography. So, it really gives one an opportunity to reflect back and see what these people looked like, in their younger years. And I think that carries a lot of weight. You know, I’d like to think it was my talent as a photographer that’s powering it through, but it really is—

AF: Well, that’s one of the great strengths of medium. It’s one of the things, I believe, that separates it from drawing or painting. Nothing renders like a photograph does.

A: Yes, it has a lot to do with the fact—you know, I always say my subject matter is the fact that I did these pictures and I managed to take the time to be consistent and to consistently do them. And with any photographer, in any body of work that they do, it’s really- when it comes down to it; it’s about taking the pictures. It’s not about talking about it or conceptualizing about it, or wishing you’d done it. If you’re out there working day-to-day and doing it, that’s so much about what you are as a creative person. And so few people actually are willing to make that commitment. You know, a lot of photographers will say, “Well, gee, I can’t get this off the ground.” I say to them…well do you live it, breathe it, seven days a week, 12 hours a day? Because that’s what the big guys do. And so, that’s just what it takes. That’s why I’m not a photographer, and I’m not out there in the world as a photographer, because I don’t have that time and I don’t have the commitment and my whole life is directed in a different area. But I’ve managed to, in my spare time, create this meager little record—

AF: Well, it’s not that meager now, not at all.

A: Yes, true, , but it’s sort of a record. And, you know, I have proximity and access, so that’s helped; I recognize that. And so, I’ve taken advantage of it.

Q: On a personal level how important are, like, photos of your mother and father or your wife or your kids?

A: Very important.

Q: So the portrait becomes a mirror of, lets say, of very deep feelings you have about who you are and people that you love?

A: Yes, I would say I spend as much time, maybe more time, on my personal pictures of my personal family and friends, more than I do even on my so-called artists portraits. I’m very serious about that.

[caption id="attachment_2146" align="aligncenter" width="600"]

Portrait of Manuel Alvarez-Bravo by David Fahey[/caption]

AF: Wow…

A: Which was pretty wild, and he signed them and that was kind of my memory of our encounter. And of course, we did business with Kertesz over the years and so we had that kind of relationship.

Q: Did you ever photograph Josef Koudelka?

A: Yes.

AF: Well, I remember we came into your gallery one day together.

A: Yes and I photographed him sitting on that couch. Yeah, I don’t think he liked it.

AF: Oh, he is shy. I have a number of portraits I’ve taken of him.

A: I have, actually—it’s not a bad picture of him.

AF: And Cartier Bresson was shy also. I photographed Bresson in his Paris apartment—

A: Yes, see I’d love to have been able to photograph Bresson.

AF: But, I mean, I never got like a one-on-one, looking into the lens kind of a portrait, but I have Bresson working with Robert Delpire when they were laying out one of his books in Bresson’s apartment. They had a bunch of 5x7s-prints on the floor that they were sequencing and I was just like, kind of like a fly on the wall, just pulled back and took my shot.

A: That’s what you have to do; that’s what you have to do. I always thought—sometimes I thought maybe if I did that when I was meeting them as a gallerist that it would be like an intrusion or an opportunistic kind of thing because all of a sudden I’d pull out my camera and take a picture. Only one person turned me down to take their picture and that was Sarah Moon, she said “No, lets do it tomorrow”, which regretfully never happened.

Q: Do you think there’s a way to define what makes a great portrait in a photograph? I mean, do you think there are certain things that have to be met or accomplished, in a sense? For you, what makes a great photographic portrait?

A: Well, it’s a lot of different things, but I think the time and the place are two very important things because my pictures are my pictures and—let me read here from one of my diaries—“every time I make a picture I know this moment will never come again, there is something historical, creative and exciting about documenting the faces of talented individual artists who, in some cases, change the way we think and interpret our lives.” In my view, art is whatever changes you, transforms your thinking and makes you re-calibrate your perception.

AF: Amen, amen.

A: Yes, and I’m looking at someone who is capable of that. And so, now I have to make a picture of them. And so, I believe the interesting qualities, whatever they may be, are inherent in the gesture, the posture, the pose, the eyes, the face, the way they look into the camera, the way they look away from the camera, I think it’s all there. And I think it’s there for that moment, at that time, and it could be a little different tomorrow, in another place, in another time, what not. But I think it’s my opportunity to really capture that moment and I think with my pictures, you know, an aspect that you can’t deny is that as much as I would like to think that they’re all incredible pictures, a part of their interest lies in the fact that it’s now 30 years later and these people came from photography. So, it really gives one an opportunity to reflect back and see what these people looked like, in their younger years. And I think that carries a lot of weight. You know, I’d like to think it was my talent as a photographer that’s powering it through, but it really is—

AF: Well, that’s one of the great strengths of medium. It’s one of the things, I believe, that separates it from drawing or painting. Nothing renders like a photograph does.

A: Yes, it has a lot to do with the fact—you know, I always say my subject matter is the fact that I did these pictures and I managed to take the time to be consistent and to consistently do them. And with any photographer, in any body of work that they do, it’s really- when it comes down to it; it’s about taking the pictures. It’s not about talking about it or conceptualizing about it, or wishing you’d done it. If you’re out there working day-to-day and doing it, that’s so much about what you are as a creative person. And so few people actually are willing to make that commitment. You know, a lot of photographers will say, “Well, gee, I can’t get this off the ground.” I say to them…well do you live it, breathe it, seven days a week, 12 hours a day? Because that’s what the big guys do. And so, that’s just what it takes. That’s why I’m not a photographer, and I’m not out there in the world as a photographer, because I don’t have that time and I don’t have the commitment and my whole life is directed in a different area. But I’ve managed to, in my spare time, create this meager little record—

AF: Well, it’s not that meager now, not at all.

A: Yes, true, , but it’s sort of a record. And, you know, I have proximity and access, so that’s helped; I recognize that. And so, I’ve taken advantage of it.

Q: On a personal level how important are, like, photos of your mother and father or your wife or your kids?

A: Very important.

Q: So the portrait becomes a mirror of, lets say, of very deep feelings you have about who you are and people that you love?

A: Yes, I would say I spend as much time, maybe more time, on my personal pictures of my personal family and friends, more than I do even on my so-called artists portraits. I’m very serious about that.

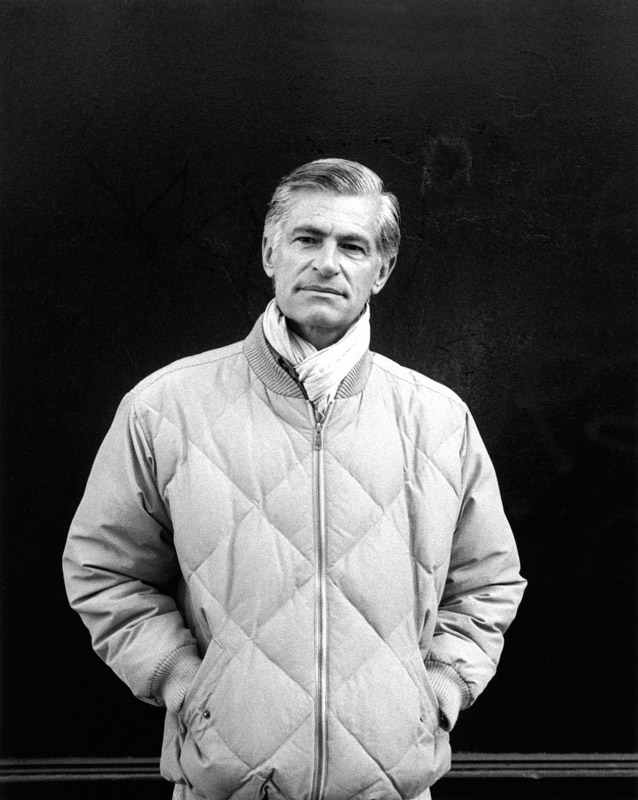

[caption id="attachment_2146" align="aligncenter" width="600"] Portrait of Helmut Newton by David Fahey[/caption]

Q: Is it important to you that people look physically attractive in their pictures? In the portraits you took of them. In your selection process, was that something you thought much about? How well they looked or how attractive they appeared? Did you concern yourself with it, when you were photographing them, by picking certain angles on their face for example?

A: I know how to read light, to a certain extent, and so obviously it’s my intention to present them in a way that’s not offensive or not inaccurate. But we look the way we look, I figure that’s our lot in life; you can’t change how you look. It just is what it is and you can’t, as a photographer, freak out about it too much and as a subject you can’t freak out about it too much either. A lot of people do, on both sides. You just can’t worry about it. And I think, for me, I want to honor you (the subject) by showing people, the ones that are admirers of your work, what you look like as a human being, that’s all I’m doing.

Q: Would you include “The Nude” in the realm of portraiture?

A: No. No. But it could be, it can be in certain pictures.

[caption id="attachment_2142" align="alignleft" width="200"]

Portrait of Helmut Newton by David Fahey[/caption]

Q: Is it important to you that people look physically attractive in their pictures? In the portraits you took of them. In your selection process, was that something you thought much about? How well they looked or how attractive they appeared? Did you concern yourself with it, when you were photographing them, by picking certain angles on their face for example?

A: I know how to read light, to a certain extent, and so obviously it’s my intention to present them in a way that’s not offensive or not inaccurate. But we look the way we look, I figure that’s our lot in life; you can’t change how you look. It just is what it is and you can’t, as a photographer, freak out about it too much and as a subject you can’t freak out about it too much either. A lot of people do, on both sides. You just can’t worry about it. And I think, for me, I want to honor you (the subject) by showing people, the ones that are admirers of your work, what you look like as a human being, that’s all I’m doing.

Q: Would you include “The Nude” in the realm of portraiture?

A: No. No. But it could be, it can be in certain pictures.

[caption id="attachment_2142" align="alignleft" width="200"] Portrait of Andre Kertesz by David Fahey[/caption]

Q: Like the photographs of Lisa Lyon, by Robert Mapplethorpe? Or what about Helmut Newton’s photographs?

A: Well, like the portrait Helmut did of Charlotte Rampling, for example. Sure, it’s a portrait of her and it’s a nude as well. David Hockney has got his shirt off, that’s not a nude, but there are instances where nudity is a part of the portrait. But in general, Helmut Newton’s nudes, I don’t consider them portraits per se. They’re more narratives, if anything. It’s like internal stories that are emerging in one frame or maybe a series of pictures.

Q: Do you give any credence to the idea that you capture a person’s soul when you take their picture? For example, the Chinese believe they don’t want their children photographed because their soul will somehow be stolen. Do you have any faith in that idea; do you validate the concept at all?

[caption id="attachment_2143" align="alignright" width="200"]

Portrait of Andre Kertesz by David Fahey[/caption]

Q: Like the photographs of Lisa Lyon, by Robert Mapplethorpe? Or what about Helmut Newton’s photographs?

A: Well, like the portrait Helmut did of Charlotte Rampling, for example. Sure, it’s a portrait of her and it’s a nude as well. David Hockney has got his shirt off, that’s not a nude, but there are instances where nudity is a part of the portrait. But in general, Helmut Newton’s nudes, I don’t consider them portraits per se. They’re more narratives, if anything. It’s like internal stories that are emerging in one frame or maybe a series of pictures.

Q: Do you give any credence to the idea that you capture a person’s soul when you take their picture? For example, the Chinese believe they don’t want their children photographed because their soul will somehow be stolen. Do you have any faith in that idea; do you validate the concept at all?

[caption id="attachment_2143" align="alignright" width="200"] Portrait of William Klein by David Fahey[/caption]

A: No, no, I don’t think there’s any truth to that—it’s a superstitious kind of thing, but I think you can capture an aspect of their soul, if you’re lucky, and you’re a decent photographer. But you don’t take it away and diminish their internal—they think you’re taking it from them and they won’t have it anymore. It’s not that, you’re just making a picture of it and taking that. You’re not taking anything from them.

Q: So you don’t think there’s any truth to the idea that you capture a person’s soul when you take their picture?